Wenjie Cai and Hwan-Ching Tai discuss the possible influence of alchemy in Cremonese wood treatment, in this extract from the December 2021 issue

The following extract is from The Strad’s December 2021 issue feature ‘Wood Treatment: The Magic Touch’. To read it in full, click here to subscribe and login. The December 2021 digital magazine and print edition are on sale now

Alchemy around Cremona

So far, scientists have found more than two dozen ingredients in Cremonese varnishes, and at least eight mineral additives in Cremonese woods. Such chemical complexities greatly exceed the expectations of violin makers and scholars. It is very likely that Cremonese makers had consulted experts with alchemical knowledge, but who might they be?

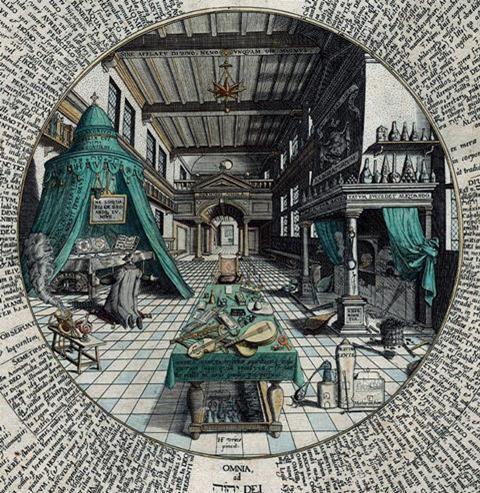

The word ‘alchemy’ of medieval Europe comes from the Arab al-kimiya (the prefix ‘al’ is a definite article), which may have originated from khemia (black earth) in the Coptic language or kim-iya (golden juice) in southern Chinese dialect. Gerard of Cremona (1114–87) translated the first practical chemistry manual into Latin: Liber de aluminibus et salibus (LAS, ‘The Book of Alums and Salts’). All the mineral additives found in Cremonese woods had been described in LAS, and were easily obtainable from local apothecaries. There was also a Hebrew copy of LAS circulating in northern Italy in the 16th century, which contained marginalia about a reader’s discussions with Giovanni Battista Nazari, an alchemist who published Della tramutatione metallica sogni tre in Brescia in 1572.

Medieval alchemy had three levels of meaning. In its narrow sense, ‘transmutation alchemy’ was the futile pursuit of turning base metals into gold. In a broader sense, ‘practical alchemy’ was the technology for producing metals, medicines, perfumes, pigments and suchlike. Then there was ‘spiritual alchemy’, a system of philosophy that sought to decode the mystery of living and non-living things, intertwined with astrology, occultism and magic.

Alum, salt and potash were all employed in the practical alchemy of gut string making. In 1663, string makers of Padua used high-purity potash (K2CO3 obtained by heating ‘winestones’, potassium bitartrate) for cleansing, table salt for preserving, and alum for stiffening. So Stradivari probably knew about these chemicals for the violin business. Moreover, Stradivari’s young adult life was closely associated with two senior architects: Alessandro Capra (also an engineer) and Francesco Pescaroli (also a woodcarver), who may have possessed practical knowledge about wood coating and wood preservation.

The first chemistry professorship in Italy (Ad lecturam Chymiæ) was established at the University of Mantua by the Gonzaga family in 1625. The curriculum followed the chemical medicine of Paracelsus (1493–1541), the father of modern toxicology, who was more interested in manufacturing medicines than creating gold. The Gonzagas even asked Claudio Monteverdi (1567–1643), a former employee, to help acquire chemical reagents and laboratory equipment.

Monteverdi grew up in Cremona as the son of an apothecary (druggist) and continued to practise alchemy throughout his career. His friend Paolo Piazza even called him ‘gran professor della chimica’. In Monteverdi’s time, the symbolism behind alchemy was the search for perfection and the purification of the soul. Although there was no historical record of interactions between Monteverdi (a viol player) and Amati, it would not be surprising if they had discussed alchemical issues in music.

Read: Wood treatment: The magic touch

Read: Trade secrets: Wood ponding

Read: Wood treatment: Choosing resonant wood

-

This article was published in the December 2021 ‘Double Basses of Venice’ issue

The north Italian city-state produced some of the country’s finest instruments . Explore all the articles in this issue

More from this issue…

- The Venetian double bass

- Celebrating Bottesini’s 200th anniversary

- South African cellist, composer and vocalist Abel Selaocoe

- Wood treatment on Cremonese instruments

- Heifetz as a teacher

Read more playing content here

-

No comments yet