Approach scales with commitment, imagination and daring, and they will inspire your cello playing, argues Mats Lidström

This article was originally published in The Strad’s April 2012 issue.

Scales make up much of what is beautiful in cello music, and as such they rely on a creative mind when it comes to bow speed, bow distribution and the choice of bowings. Add in musical expression and dynamic control, a brave approach to fingerings, and a commitment to minimising string-crossings and audible shifts, and scales can be a powerful source of inspiration for practice and performance.

Some musicians look at scales as warm-up material. This is a misjudgement. You should be properly warmed up even before starting to play them, in order to execute the stretched positions and double-stops with a balanced left hand, and to play string-crossings with a bow that can respond to every type of contact with the string. Warming up enables us to draw on our full potential, and should precede anything that requires musical expression, such as scales.

When you are warmed up, you may well reach for a scale book to guide your practice. Unfortunately, most books on cello scales are outdated and based on a 19th-century idea of how to manoeuvre on the fingerboard. The old, pre-Casals school seemed to be about how to get around the instrument while avoiding difficulties, and using shifts that are as short as possible. Playing the cello thus becomes an exercise based on fear, rather than a musical adventure full of daring (compare the safe, conservative fingerings in example 1 with the flashy, bold fingerings that could replace them).

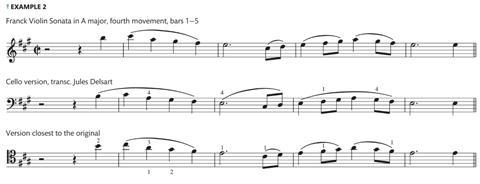

How do we counter this? Casals’ friend, the composer and musicologist Donald Tovey, said that every instrument has a tendency to encourage mannerisms that have no real musical sense, but which easily become accepted as ‘natural’. This may be especially true for the cello. But if we agree that there are three instruments technically superior to ours – the voice, the piano and the violin – we can use them as reference points for everything we do, including the technical solutions we arrive at. We can even compare our interpretations with theirs, just to check that we are not basing our artistic choices on what we imagine is ‘natural’ for our instrument. A case in point is Jules Delsart’s 1888 cello arrangement of Franck’s A major Violin Sonata. Delsart’s version avoids many of the work’s exciting technical challenges, especially in the opening of the fourth movement (see example 2), which to me looks like it is meant for the double bass.

In my first lesson at the Juilliard School, my teacher Leonard Rose said quite casually, ‘You’ll learn as much from your violinist friends as you will from me.’ Clearly he wanted me to look towards a superior instrument. Voltaire’s famous quip to cellist Jean-Louis Duport after hearing him play – ‘You make me believe in miracles: you know how to make a nightingale out of an ox’ – hints at the cello being perceived as slow and clumsy.

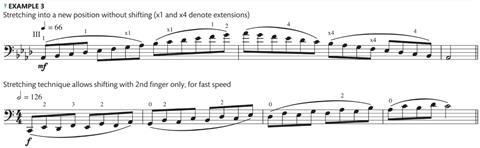

This is where Casals stepped in. He modernised cello playing by bringing in elements of violin technique. His principle of expressive intonation outlined the harmonic function of every note within the scale, enabling the cello to bring out the vertical structures (or harmonies) of a score – a goldmine when playing a Bach suite, for example, where the bass-line is hidden. And with the introduction of the stretching, or extension, technique, Casals created the illusion of a shorter fingerboard: he effectively made the instrument smaller. His new ideas helped minimise, and in some instances eliminate, shifts (see example 3).

Shifts that are not part of an interpretation, in the form of articulation or a beautiful glissando, must not be audible. This is especially apparent with scales. If you are not physically able to stretch, say, an octave in first position, then try stretching as much as possible. Any effort you can make shortens the neck of the cello, making the movements less audible. However, stretching affects the balance of the hand, and therefore the vibrato, so you need to stay alert to the note’s beauty (or loss of beauty) and prioritise accordingly.

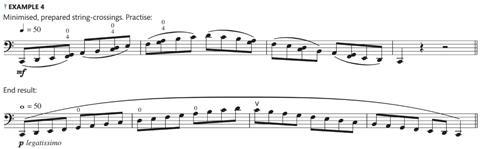

Minimising string-crossings is another way to make your playing look easy while saving time (see example 4).

Listeners should not get the impression that we play a big, clumsy instrument – that Voltaire’s ox is our favourite animal – when in fact we can take a beautiful line beyond mere down bows and up bows. Watch your right arm and note which movements create delays, making string crossings sound laboured and lacking in direction. You can easily minimise string-crossings by monitoring the gap between the string and the hair of the bow. Not much is actually needed to make the crossing, and the gap will show the way: close the gap, and the string-crossing is minimised. Perfect for a scale across four strings!

The bow arm's importance when practising scales should never be underestimated. Commitment with the bow gives the scale direction and pulse, shifting our attention to how it sounds and away from the area that is usually perceived as more difficult: the left hand. If you are preoccupied with your left hand you could lose the pulse by making uncommitted bow changes or simply by backing away from a powerful, courageous dynamic. Losing steam in areas where the ear does not particularly wish to detect poor confidence will affect the intonation, and running out of bow is as uncomfortable for the performer as it is for the listener. How to save bow, or deciding whether one note may need more bow than another in order to constantly control the scales, is very much part of scale practice.

A committed bow means that a scale is never musically ‘switched off’. Adding musical expression will ensure that the scale never sounds static or predictable. The bow stroke should mean much more than just moving from frog to tip: consider the vertical motion between the hair of the bow and the stick itself Controlling this aspect of the bow movement will give greater variety to every note as well as unlimited characteristics to the beginning of it – the attack. With an ever-listening and constantly tuned-in ear, you will never play a scale with bow strokes that could be described as scrubbed, brushed or sawed.

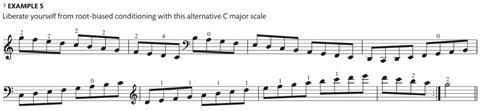

Let's return to the raw materials – the notes on the page. If most of the available scale books are deficient, what should we look for in a modern method? I believe we need something that addresses old problems in a new light, and stops us going on autopilot. Standard scales can be practised in many different ways, and they can be formatted differently so you might need a little extra time to identify the key and familiarise yourself with the new shape. In The Jazz Theory Book, pianist Mark Levine says that the goal when practising scales is to deprogramme yourself from years of root-biased conditioning. His refreshing idea is to leave behind the concept that a C major scale must start and end on a C. It may just as well start on a D or any other note belonging to the C major scale (see example 5).

Naturally, this applies to arpeggios, 3rds or any of the scales we find in a scale book. Nor does the scale have to start from the bottom. Indeed, starting from the top will eliminate the familiar feeling of the scale being easy at the beginning and difficult at the end. By turning it around, we will likely feel most relaxed at the top. The graphical reshuffling of scales will be confusing at first, even if it increases our practising options tenfold. But over time, familiarity with the new shapes will clarify, enlighten and inspire.

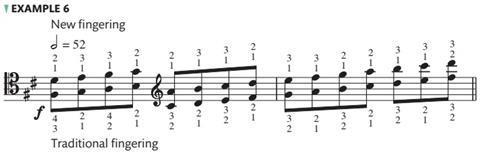

Alongside rejecting root-biased conditioning, we need to overhaul the traditional fingering for 6ths, which simply does not work. It may look good on paper, but every change from a major 6th to minor 6th is audible, and artistically there is nothing you can add or shape. Legato is impossible, for instance. The instant argument against the improved, modernised fingering (first and second finger for minor 6ths and first and third finger for major 6ths) is that you need to move the arm for each shift. But when you get used to it, and develop your muscle memory, this new fingering (see example 6) feels comfortable, and suddenly, playing 6ths becomes a lyrical affair.

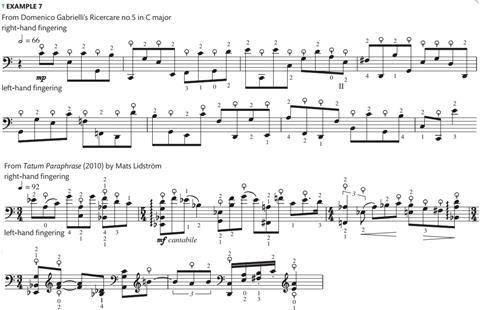

Any new scale book should also address, as a matter of urgency, the artistic concept of pizzicato. This is rarely examined, or taught, despite its frequent use. It should be the ear that determines which finger produces the most beautiful, round, short or heavy pizzicato (see example 7).

A round pizzicato, for instance, may need more than the fingertip of an index finger to project, and when the ear has picked up on that, it may well be that one never plays pizzicato with any finger other than the thumb. The tempo often decides the fingering, of course, but whatever the choice, it should be made for artistic reasons.

A fully worked-out system of fingerings for each scale negates the old belief that C major is easier than C sharp major or that E flat minor is more difficult than E minor. Thanks to the flawless organisation and discipline of a system, the scales all follow the same principle, allowing the key and its fingerings to be immediately identified. Much will eventually rely on muscle memory, so that in the end you find yourself more occupied with drilling the muscle memory than with notes. The philosopher Friedrich Schlegel warned: ‘It is equally fatal for the mind to have a system and to have none. One must try to combine them.’ Such an attitude promotes a flexible mind and is a giant step towards the release of the imagination, but it would only interest me once I had acquired a system in the first place. A system is also excellent for sightreading when you need to identify an approaching scale or passage quickly.

Here is a final thought to inspire your scales practice. Scales are very much part of concert music, so they have to be worthy of the concert hall. Performance is primarily about listening, but it is also about watching. On stage, fingerings must not have anything to do with what fits the cello, or what is ‘safe’. Brave, brilliant fingerings, based on projection instead of taking short cuts, make the instrument sound open and free. And they are exciting to watch. In the end, musical expression must command the intellect, scale system or not, and an audience always responds to warmth.

This article was originally published in The Strad’s April 2012 issue. Mats Lidström’s book of cello scales – The Beauty of Scales for Cello– is published by CelloLid.com.

No comments yet