- News

- For Subscribers

- Student Hub

- Playing Hub

- Directory

- Lutherie

- Magazine

- Magazine archive

- Whether you're a player, maker, teacher or enthusiast, you'll find ideas and inspiration from leading artists, teachers and luthiers in our archive which features every issue published since January 2010 - available exclusively to subscribers. View the archive.

- Jobs

- Shop

- Podcast

- Contact us

- Subscribe

- School Subscription

- Competitions

- Reviews

- Debate

- Artists

- Accessories

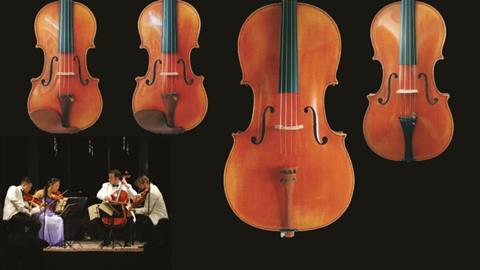

Game, set and match: quartets of instruments

Four instruments from the same tree, varnished from the same pot, played by a single quartet. Is this the way to perfect harmony? Katherine Millett investigates in this article from August 2008

Television cameras greeted the Miró Quartet’s arrival at Alice Tully Hall, New York, in February 2003. ABC News ran an evening feature about the concert and the New York Times raved about it – and about the group’s two violins, viola and cello, which were made recently by French luthier Frank Ravatin. ‘It wasn’t only the phrases that nestled together like the pieces of a jigsaw puzzle, clear-edged and close-fitting,’ wrote New York Times reviewer Anne Midgette. ‘The Miró’s actual instruments are cut from the same wood.’

Romance surrounds instruments formed from the same tree, varnished from the same pot. Bound by nature as well as by craft, they seem destined to transcend human conflicts, to enhance the uniquely intimate music of the string quartet. What could be more complete than the prospect of four musicians feeling and thinking together as they draw great music from instruments that breathed together as a sapling?

Two years later, however, only two of the Ravatins remained with the Miró. The instruments had not served all four members of the quartet equally nor, ultimately, the group as a whole. First violinist Daniel Ching and violist John Largess continue to relish the unity of sound they find in their Ravatins. ‘I like it that my viola and Daniel’s violin share some blending characteristics,’ says Largess, ‘because he and I have always had the most difficult time blending our sounds.’

Yet the three upper voices of the Ravatin quartet sounded so cohesive that the Miró decided blending could be too much of a good thing. ‘John had a hard time hearing my sound,’ says second violinist Sandy Yamamoto. ‘It blended too much with Daniel’s. All the Ravatins had a very nice blend, but it was hard to separate textures, especially for the inner voices.’

Cellist Joshua Gindele concluded that his instrument simply didn’t suit his personality: ‘When my bow hit the string, I felt I had to push.’ (Yamamoto now plays a Benjamin Ruth violin and Gindele plays a Phillip Injeian cello.)

Ravatin was surprised by the Miró’s reactions. ‘I thought the cello was one of the best I had ever made,’ he says. ‘The quartet liked the viola very much, but for me it was the most doubtful of the four instruments.’

Also surprised was Eric Chapman, a founding member of the Violin Society of America (VSA). ‘I heard the last concert the Miró gave on all four Ravatins,’ Chapman says, ‘and it was an incredible sound, so matched that it was like one instrument. That concert remains a memorable experience. I think it was a big mistake for the other two not to keep theirs.’

Ravatin and other makers of matched sets (defined here as those instruments intended to be played as a quartet, made by the same maker using the same wood and the same varnish) insist that similar wood does not necessarily produce similar sound.

‘Wood has very little influence on the sound of a stringed instrument,’ says Stefan-Peter Greiner of Bonn, Germany, whose matched set is played by the Keller Quartet. ‘I buy whole trees, so I can compare. I have made many instruments from a tree that began growing in Austria 450 years ago, and they sound completely different.’

Ravatin undertook the commission as an experiment conceived by philanthropist Mark Furth, and he has since made a second quartet. ‘When I made the set for the Miró,’ Ravatin says, ‘I thought of it as one instrument with 16 strings. With more distance, I see that a quartet needs a lot of colours in the sound, so one needs to concentrate on making four individual instruments, not one.’

Already subscribed? Please sign in

Subscribe to continue reading…

We’re delighted that you are enjoying our website. For a limited period, you can try an online subscription to The Strad completely free of charge.

* Issues and supplements are available as both print and digital editions. Online subscribers will only receive access to the digital versions.