Ending on Monday 15 October, the Tokyo Stradivarius Festival 2018 has brought together 21 of the finest Stradivari instruments from all over the world, together with some of the master’s tools and templates, an acoustic demonstration, and concerts performed on several of the instruments.

No name echoes so widely in the history of the violin as Antonio Stradivari. The Tokyo Stradivarius Festival brings together in a unique exhibition 21 of the Cremonese master’s finest instruments, including eleven golden-period violins, a precious viola, and a guitar that will be making its first ever journey to Japan. This exhibition, curated by violin maker Gregg Alf, is the first of such a scale to take place in Asia. As Japan gears up for the 2020 Tokyo Olympics, 2018 is the year to celebrate music and culture, and this festival is a historic part of that.

Among the instruments from Stradivari’s early period in the exhibition is the iconic ‘Sabionari’ guitar of 1679. One of only a handful of surviving Stradivari guitars, and the only one that is playable, the ‘Sabionari’ will be making its first ever appearance in Asia at the exhibition. It might surprise many people that Stradivari made guitars, but the guitar was quite a popular instrument in the late 1600s, and during his lifetime Stradivari also created mandolins and harps.

Another early-period violin on display is the 1690 ‘Medici, Tuscan’, which is owned by the Santa Cecilia Academy in Rome. This was one of two violins in the ensemble made for the Grand Duke of Tuscany, Ferdinando de’ Medici. The Hills, in their 1902 study Antonio Stradivari: His Life & Work (1644–1737), described the ‘Medici, Tuscan’ as one of the most outstanding Stradivaris in existence, writing that: ‘Of all the violins made in the period previous to 1704, the “Tuscan” represents most perfectly the greatness of his ability.’

From the last years of the 17th century comes the ‘Kustendyke’ violin of 1699, kindly loaned to this exhibition by the Royal Academy of Music in London. Stradivari worked tirelessly to improve his creations, and in the 1690s he was developing new ideas and concepts, which led to him adopting a ‘long pattern’ for his violins. The ‘Kustendyke’ bears all the unique features of this period. More than half of the instruments in the exhibition belong to Stradivari’s golden period, and there can surely be few better examples of this era than the 1704 ‘Viotti’ violin. The name is taken from one of the owners, Giovanni Battista Viotti (1755– 1824), a virtuoso who once served as Marie Antoinette’s personal violinist. This historic instrument is a true masterpiece, and with its powerfully focused bass sound and rich and beautiful treble is a perfect representative of Stradivari’s golden period. The violin is now part of the Munetsugu Collection and is on loan to the violinist Fumiaki Miura.

Another iconic violin from Stradivari’s golden period is the 1717 ‘Kochanski’, which has been kindly loaned to this exhibition by the worldrenowned violinist Pierre Amoyal. Still in pristine condition, it was named after its one-time owner the Polish violinist and composer Paul Kochanski (1887–1934). The ‘Kochanski’ was stolen from Mr Amoyal in 1987 but was recovered and returned to him four years later.

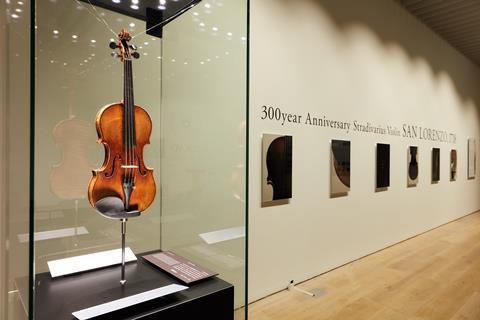

One of the most notable Stradivaris in the exhibition is a violin that celebrates its 300th birthday this year, the 1718 ‘San Lorenzo’. Aside from the significance of its anniversary, this violin is remarkable for the Latin inscription on its sides, which makes it unique among all surviving Stradivari instruments. The text ‘Gloria et divitiae’, barely visible on the centre treble rib, is followed by the clearly visible ‘in domo eius’ on the centre of the bass-bar side. The inscription alone attests to the violin’s significance and, like the 1704 ‘Viotti’, the instrument was once owned by the eponymous virtuoso.

The 1722 ‘Rode’ violin comes to the exhibition on loan from the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford. It is one of only eleven decorated Stradivaris still in existence, five of which are at the Smithsonian Museum in Washington DC, and four – a complete decorated quartet – in the Royal Palace in Madrid. From Stradivari’s final years we have the remarkable 1732 ‘Red Diamond’ violin. This was a favourite of violin expert and author George Hart (1839–91), who gave it the name ‘Red Diamond’ on account of its superlative tone and condition and its exquisite colour. The violin has a turbulent history. Luigi Tarisio (c.1790–1854) and Jean-Baptiste Vuillaume (1798–1875) were among its early owners, and after the violin passed to owners across the Atlantic, it finally landed in the hands of Sascha Jacobsen, first violinist of the Musical Art Quartet. On 16 January 1952 a violent storm hit Los Angeles, where Jacobsen served as concertmaster of the Los Angeles Philharmonic. The violinist was driving along a coastal road when his car was engulfed by flood waters. Jacobsen barely saved himself but the ‘Red Diamond’ was swept out to sea in its case. However, it miraculously resurfaced on the shore the next day and, after a most skilful restoration, was returned to playing condition.

Another of Stradivari’s finest violins from his late years is the 1736 ‘Roussy’. It is a priceless piece, made just a year before the maker’s death at the age of 93. The history of this Stradivari begins at the end of the 18th century in Madrid. The violin then travelled to London where it was offered to the Hills for £500 in 1878. Although the Hills did not buy it at the time, they did purchase it some years later, and then sold it to the first president of the Nestlé group, Émile-Louis Roussy (1842–1920). Today, the owner is the violinist Chisako Takashima.

Among Stradivari’s most rare and exquisite creations are his violas. One of only ten surviving violas by the Cremonese master, the 1734 ‘Gibson’ is a truly precious instrument, as it is the last viola Stradivari made before his death. We are able to showcase the ‘Gibson’ in this exhibition thanks to the support of the Habisreutinger Stradivari Foundation, which for many years has supplied the instruments for the Stradivarius Summit Concert given in Tokyo by members of the Berlin Philharmonic.

Only around 60 Stradivari cellos survive today, and one of them, the 1717 ‘Bonamy Dobrée, Suggia’, will be part of this exhibition. This cello was built on Stradivari’s ‘forma B’ model, which he introduced in about 1707. The Hills praised this model as the ‘ne plus ultra of perfection’, and wrote that the ‘forma B’ cellos ‘stand alone in representing exact dimensions necessary for the production of a standard of tone which combines the maximum power with the utmost refinement of quality, leaving nothing to be desired: bright, full and crisp, yet free from any suspicion of either nasal or metallic tendency’.

The exhibition will also display, for the first time in Asia, the tools and moulds that Stradivari used in his workshop. These come to Japan courtesy of Cremona’s Museo del Violino, where they are housed. Seeing the precious internal moulds together, with their subtle variation in lengths, widths and proportions, will no doubt shed light on how Stradivari came to create the finest violins, and demonstrate the extent of his research as a maker.

The prices of Stradivari’s instruments, and other Italian instruments of the 18th century, have accelerated in recent years far beyond the reach of musicians. The sale price of the 1721 ‘Lady Blunt’ Stradivari violin, which was auctioned in 2011 on behalf of the Nippon Music Foundation with the proceeds going to the Great East Japan Earthquake recovery effort, was £9.8m (¥1.27bn). Many of the Stradivaris in this exhibition are in the possession of notable cultural foundations and educational institutions, which often loan fine instruments to talented musicians. Through this exhibition, we hope to highlight the importance of supporting accomplished players with instrument loans, given that the economic realities of the rare instrument market makes access to such masterpieces a challenge.

Sota Nakazawa, chairman, Tokyo Stradivarius Festival

No comments yet