Ariane Todes reviews a programme that celebrates the Stradivari mythology rather than challenging it

I’ve often wondered what it must be like to be a doctor watching an episode of a medical drama such as House, ER or Casualty. Would I be throwing sharp objects at George Clooney over his surgical etiquette? Would I be laughing at the over-loaded dialogue, simplistic morality and gratuitously happy ending? I think I have a bit more insight now, from watching last night's BBC4 programme, Secret Knowledge: Stradivarius and Me, fronted by journalist and amateur violinist Clemency Burton-Hill.

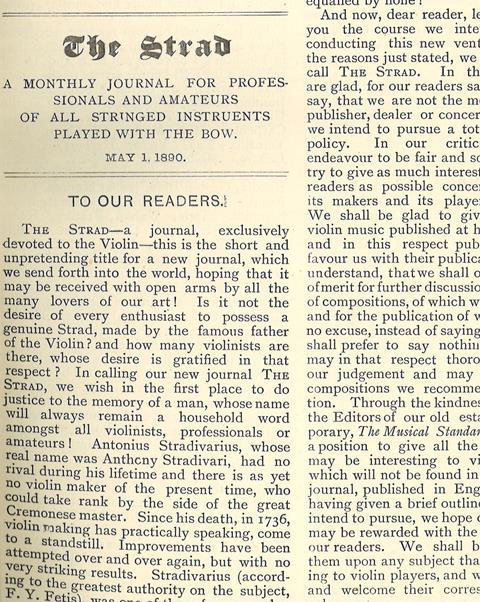

I can claim some involvement in the show – we were contacted by the BBC team about The Strad Archive, which dates back to 1890 and tells its own first-hand story about the history of the violin. I spent a happy few days head down in the archives looking for material for the show that in some way represented the concept of Stradivari’s ‘secret’. What I found time and time again was a remarkable lack of editorial about the concept – many letters claiming to have found the secret, reviews of books claiming to have found the secret, and adverts for varnish makers and luthiers claiming to have found the secret. However, the tone of the journal itself, I’m proud to say, is generally sanguine and healthily cynical. But I was able to find some lovely examples, including the first edition (see picture), for the production team to use as stills (watch out for them from 21:25).

The show was a whistlestop tour of the Stradivari legend, starting in Cremona with Amati, whizzing through Stradivari’s life and work, via Catherine de Medici (credited with turning the violin from a licentious plaything to a proper musical instrument), Viotti, the ‘Messiah’, on through the Victorian era and the story of Marie Hall. No time for much historical context or mention of Guarneri ‘del Gesù’ or Stainer, or explanation that the Cremonese violin making tradition became secret by default, inasmuch as the families carrying it died out without transmitting it (if only there had been a contemporary version of The Strad).

We were treated to some luscious close-ups of instruments such as the ‘Messiah’ and ‘Viotti’ and some more luscious close-ups of Burton-Hill and Jennifer Pike playing the Bach ‘Double’ on two Strads from the current Ashmolean exhibition, and then discussing the instruments as being 'like an old friend’. Burton-Hill held the ‘Serdet’ in her gloved hands and cooed, ‘I didn’t think I’d feel quite so emotional,’ and then the 'Messiah', declaiming, ‘I’ve been waiting for this moment for pretty much my entire life’.

Now far be it for a seasoned hack like me, who, in my role as editor of The Strad, has had the utter privilege of seeing many and playing a few Strads, to judge the authenticity of Burton-Hill’s sensibilities. But what they do show up is the progress of the Stradivari ‘myth’. For she has a perfectly sensible conversation with luthier Michael Cairns, who explains the story quite rationally: ‘Stradivari was the right man at the right time – he came out of three generations of fine Cremonese makers, he just took it that several stages stage further and had a long working life and was hugely talented. It’s a bit like Rembrandt – they all had the same paints and they all had the same canvasses, but Rembrandt had something special and Stradivarius is a bit like that.’

In other words, the secret is that there is no secret. Burton-Hill seems to have bought into this when she says, ‘Science has yet to solve the riddle of what set Stradivari apart and I wonder whether there really is a magic formula or whether he wasn’t just astonishingly good at what he did, a kind of Shakespeare or Titian whose genius can never be slavishly copied or repeated.’ 'Yes!', I whooped at the television. Yet by the end of the show, we’re back to square one: ‘I’m still enthralled by this mystery and by the fact that the answer to what makes a Strad a Strad seems to be as elusive to us as why we fall in love – it’s like the ultimate riddle, the perennial quest and a reminder that we still don’t have all the answers.’ Coming full circle the programme seemed to demonstrate that sometimes we don’t want answers – we’d much rather have mystery.

There’s one phrase of Burton-Hill’s that resonated with me: ‘Each one is like a little miracle in wood.’ Surely that applies to all stringed instruments, not just Strads, or even Cremonese. Yes, especially the old ones, the particularly aesthetically pleasing ones, those with amazing life histories or that have been held by musical geniuses. But fundamentally each and every millimetre of carefully engineered and prepared wood, along with the immense variety of sounds it produces and the emotional impact of which it’s capable, is a miracle worth celebrating – let’s hope the BBC gets to the bottom of all that one day.

Read The Strad digital edition FREE as part of a 30-day trial

No comments yet