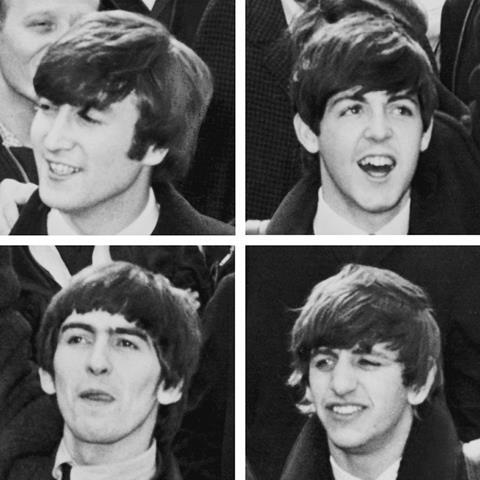

Love Me Do, the Beatles' first single, was released in October 1962. We marked its 50th anniversary with an investigation by Kate Mossman into how the Fab Four brought string music into their work

By the beginning of 1967, the band’s musical aspirations had resulted in the hiring of a 40-piece orchestra, as the most ambitious track from the 129-day Sgt Pepper recording period began to take shape. The string interlude in A Day in the Life – one of the most heady, terrifying and innovative uses of an orchestra in pop – was a practical move, bridging two separate songs: Lennon’s dreamlike observations on ‘holes in Blackburn, Lancashire’, and Paul’s little commuter tale. They would be knitted together by what Lennon described as a ‘musical orgasm’. On the score, George Martin wrote the lowest possible note for each instrument and, after 24 bars, the highest. Then he put a squiggly line in between.

Leading the orchestra on that day was Erich Gruenberg, who’d met Martin at the Guildhall School of Music & Drama and went on to become concertmaster of the London Symphony and Royal Philharmonic orchestras. Now 87, Gruenberg recalls that a psychedelic squall of that kind was not entirely outside his musical experience. ‘In certain kinds of modern classical music, composers had done that already,’ he remembers. ‘The idea was to have a rising excitement, starting at a certain spot and then all working together developing this improvisatory idea, and repeating it until they got the result they wanted.’

The song took 34 hours to record but as far as Gruenberg was concerned, the glissando wasn’t difficult: ‘We didn’t have too many takes – I think we recorded it in half an hour. I found it fascinating.’ And Lennon wasn’t as shy and awkward as he made himself out to be either. ‘The Beatles were tremendously charismatic and of course they had ideas of what they wanted,’ Gruenberg reflects. ‘But they did not have the symphonic experience. That was where George Martin came in.’

Gruenberg was the one wearing the gorilla paw in the video. ‘That was a new experience for me,’ he says. ‘We always dressed very formally. Back then it was tailcoats, now it’s open collars – and that’s fine.’

If the costumes and paraphernalia helped to make an affectionate cartoon of the old-fashioned symphony orchestra, they also reflected the song’s sinister lyrical dream world. Lennon became increasingly sick of people trying to interpret his songs. I Am the Walrus, perhaps his most mysterious nonsense lyric of all, came about when he discovered a teacher at his old primary school was trying to get his pupils to analyse

Beatles songs. Hence lines such as ‘Yellow matter custard, dripping from a dead dog’s eye.’ Fittingly for a song of such roaming, free-for-all energy, the Walrus chord structure uses each letter in the musical alphabet in succession – A–B–C–D–E–F–G – with strings and bass stomping out scales in contrary motion.

Martin recalls a devil-may-care attitude from Lennon when it came to the string arrangements. ‘I Am the Walrus was fun,’ he says. ‘After we had completed the track and guide vocal, I asked John what he wanted me to do with it. He said, “Oh, your usual stuff – a bit of cellos and brass, you know.” I said, “Fine, do you want to come back to my place and we can work it out?” He looked at me, horror-struck. “No!” he said. “That’s your job!”’

Martin’s resulting orchestration works actively alongside the lyric, painting the absurd words with triplets and glissandos. ‘I just let rip and enjoyed myself,’ he continues, ‘scoring some outrageous things, including a twelve-piece vocal group singing whoops and chants to add to the cacophony I was writing. When we recorded it in the big studio in Abbey Road and he heard what I had done, he fell about laughing. He did think it was terrific. I suppose the general reaction was surprise but no brickbats.’

The journey from Eleanor Rigby, all Vivaldi and Bernard Herrmann, to the outlandish Walrus had taken just 16 months. Glass Onion, recorded a year later, in 1968, has echoes of more avant-garde composers. ‘There are the creepy, swooping glissandos,’ says the US-based pianist, composer and Beatles fanatic Tom Loncaric. ‘It’s like Penderecki’s Threnody for the Victims of Hiroshima – a couple of minutes into that piece you can hear similar string effects.’

The Beatles’ last number one, The Long and Winding Road, which was recorded in January 1969, couldn’t have sounded more different. Produced by Phil Spector from a score by Richard Hewson, and featuring 18 violins, 4 violas and 4 cellos, it was all sugar and pathos. ‘Hewson’s arrangement is carefully crafted but reminds me of countless sentimental pop arrangements,’ says Loncaric. While Martin’s string sections were, Loncaric suggests, probably a lot of fun to play, The Long and Winding Road could have been a bit of a bore: ‘Hewson’s score contains an ample supply of semibreves and there’s not much evidence of rests. This kind of sustained and perpetually legato string writing results in a stunningly pretty tone, but it doesn’t give the listener much breathing room, hence a possible feeling of wallowing in syrup. For the players, it gets tiresome employing constant long bow strokes and focusing on the intonation of one pitch, for what seems like an eternity.’

Spector’s stereo mix – a shimmering string section coated in echoes and reverb, in his signature Wall of Sound style – sounds strangely dated today. McCartney famously hated it (he wasn’t present for the overdubs) and in April 1970 sent a list of demands to the Beatles’ manager, Allen Klein, including: ‘Strings, horns, voices and all added noises to be reduced in volume’, ‘Vocal and Beatle instrumentation to be brought up in volume’, and finally: ‘Don’t ever do it again.’

Unfortunately he was too late, and the track came out, syrup and all, just a month later on Let It Be. Within six months the Beatles were gone. Years later McCartney himself would try writing for full orchestra with his 1991 work Liverpool Oratorio, followed by Ecce Cor Meum in 2006 and, most recently, the ballet Ocean’s Kingdom.

Though it’s generally agreed that McCartney’s genius lay with the magic combinations of an eight-note scale, not with the machinations of an entire symphony orchestra, the Beatles’ enthusiasm for classical adventure cast a long shadow. Orchestral arrangements became intensely fashionable directly after they disbanded, with arrangers such as David Bedford sprinkling the albums of Kevin Ayers, Mike Oldfield and Roy Harper with a nostalgic, pastoral echo. Perhaps we have the Fab Four to thank for these wispy rock wonders. ‘It’s not up to me to comment on the effect our work had on other recordings,’ says Martin. ‘Let others decide.’

Click here to return to Part One.

From the October 2012 issue. Subscribe to The Strad to read articles on all facets of the string music world each month. Or click here to find out about our digital edition

Photos: Library of Congress

No comments yet