An encounter with her instrument’s human qualities was a turning point for the Japanese violist, who looks back over a long career

I don’t have many memories from when I first started playing the violin. In fact, I don’t remember much at all from before I was about ten. I was a very depressed child and music was hard work. This wasn’t long after World War II, when the economic situation in Japan was very bad. I think my mother thought it would be a good idea if I had a skill that could earn us some money, and so she practised with me for two or three hours a day, which is a lot for such a young child.

I joined the Toho Gakuen School of Music in Tokyo when I was fifteen. In those days, all violin students at the school had to study viola, too, so that’s what I did. Several years later, we travelled to the US to perform at the Tanglewood Festival. We heard many wonderful performances there, including the Boston Symphony Orchestra playing Strauss’s Don Quixote. Until that night, when I heard the orchestra’s principal violist, Joseph de Pasquale, I hadn’t known it was possible for a viola to sound so much like a human voice. I knew right away that I wanted to be a violist, but I worried that I was too small. When I went backstage to ask Mr de Pasquale what he thought, he looked at my left hand and said, ‘Hmm, not too bad.’

Technique is a useful tool but it isn’t enough on its own. You need an image, a clear idea of what you want to create with your playing. Inspiration can come from many different places: books, movies, even food, and you should make sure you always approach the world with an open mind. If you don’t, your playing won’t have the feeling of freedom that can freeze an audience with just one note. Technical ability is taking over, however.

Nowadays too many people think that bigger is better, faster is better. I once went to see an opera in a big stadium somewhere in Europe, where 40,000 of us listened to the singers through a system of microphones and speakers. That kind of performance really is meaningless, in my opinion. The Japanese word for music, ongaku, is made up of the Chinese characters for ‘sound’ and ‘joy’: 音楽. For me, the word communicates something very private, not a gigantic venue or a big, spectacular sound.

One of my greatest triumphs was being the violist of the Vermeer Quartet for five or so years in my early thirties. Every single day taught me so much. Its founder, Shmuel Ashkenasi, is a sensational musician and a wonderful person. My first chamber music teacher was the great Hideo Saito, who had been a pupil of Feuermann. I remember spending hours with him on just one or two lines of a Haydn piano trio, analysing the function of each note. Chamber music has always been closest to my heart, be it in the Vermeer Quartet, more recently in the Michelangelo Quartet, or in many other combinations.

Interview by Tom Stewart

-

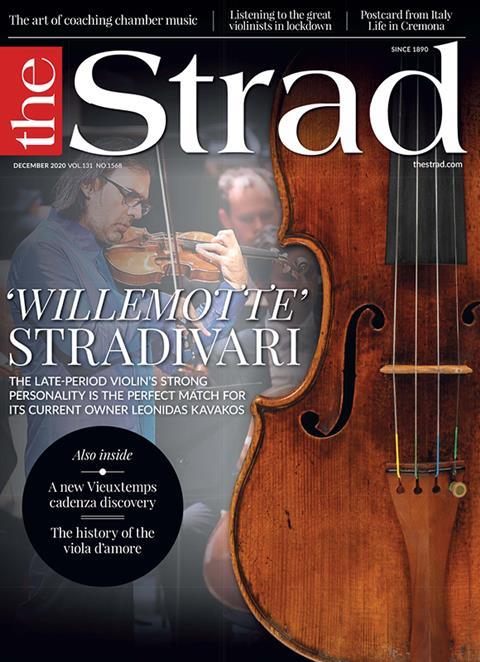

This article was published in the December 2020 ‘Willemotte’ Stradivari issue

The late-period violin’s strong personality is the perfect match for its current owner Leonidas Kavakos. Explore all the articles in this issue. Explore all the articles in this issue

More from this issue…

- The 1734 ‘Willemotte’ Stradivari violin

- A newly discovered Vieuxtemps cadenza

- Coaching chamber music for school-age students

- Amandine Beyer on recording C.P.E. Bach’s string symphonies

- The history of the viola d’amore

- Evolving interpretations of the great vioinists

Read more playing content here

-

No comments yet