Matthew Rye pays tribute to a musician whose panache and technical prowess helped popularise the cello in the US as a solo and recital instrument

Gregor Piatigorsky was an example of the all-round cellist: orchestral principal, concerto soloist, chamber collaborator, renowned teacher and generally inspiring figure. He was musically very well connected, playing with all the great conductors of the century and forming lasting trio partnerships first with Carl Flesch and Artur Schnabel, then more flexibly with Nathan Milstein and Vladimir Horowitz and later, in what Life magazine dubbed the ‘Million Dollar Trio’, with Jascha Heifetz and Artur Rubinstein.

He collaborated as a performer with Stravinsky, Strauss, Rachmaninoff and Bartók, and was also probably only second to Rostropovich in his procurement and advocacy of new works from a wide variety of the leading composers of his day. ‘Grisha’, as he was familiarly known, also mixed in wider cultural circles; he was friends with Albert Einstein, Stefan Zweig, Aldous Huxley and many other great names, and was a keen collector of art.

Even more than his older contemporary Pablo Casals, Piatigorsky was key in popularising the cello as a solo and recital instrument, touring the US in particular, and taking the cello to places where concerts were rare enough in themselves. His career also coincided with the rise of both film and television, which gave even wider exposure – his Bell Telephone Hour appearances, as well as performances with Heifetz and Rubinstein, can be found on YouTube.

Pedagogical background

Piatigorsky received his first cello for his seventh birthday and began learning from his father, a keen violinist, but he soon moved on to the local conservatoire, unperturbed by a visiting orchestral cellist who condemned him with the words, ‘Keep away from the cello. You have no talent whatsoever.’ He was soon good enough to earn his first money as a cellist, playing in a brothel and a cinema orchestra while still only eight, until, according to his anecdote-filled autobiography Cellist (1965), he was provoked into smashing a chair over the conductor’s head. He then won a scholarship to study at the Moscow Conservatoire with Alfred von Glehn and was still only 15 when he competed for, and won, the role of principal cellist in the Bolshoi Theatre Orchestra amid the aftermath of the 1917 revolution.

When Piatigorsky’s attempts to continue his studies abroad were thwarted by officialdom, he used a concert tour with fellow musicians from the Bolshoi to get himself smuggled across the Polish border and ended up in Warsaw, where he made his living for a while. By 1932 Piatigorsky was giving regular recitals on the US touring circuit

Arriving in Berlin, he managed to arrange to have private lessons with Hugo Becker, the cello professor at the Hochschule für Musik, who improved his bow hold, but linguistic complications led Piatigorsky unintentionally to insult his teacher once too often and he was out on his ear (he would say ‘Gott sei Dank’ at the end of each lesson, thinking it meant ‘God be with you’ – he was in fact saying, ‘Thank God!’). Instead, he moved on to Leipzig where he studied under the great Julius Klengel, until problems with his immigration status and penury in the face of Germany’s rampant inflation drove him back to Berlin. Here Wilhelm Furtwängler invited him to lead the cello section of the Berlin Philharmonic – at the age of 21 he had arrived, and this august position also provided the springboard for his solo career, which took off in 1928 with concerto debuts in Germany and elsewhere.

After achieving his dream of settling in the US (being Jewish himself and married to a member of the Rothschild family meant leaving his European home in Paris following the German occupation in 1940), he became a renowned teacher himself, first at the Curtis Institute of Music in Philadelphia, then at Boston University, and later at the University of Southern California in Los Angeles. He effectively trained whole generations of cellists, numbering among his pupils Mischa Maisky, Jeffrey Solow, Raphael Wallfisch and Erling Blöndal Bengtsson.

Technique and Interpretative Style

Piatigorsky’s patrician bearing and lofty frame give the visual impression of him offering the cello – which almost looks diminutive in his hands – and its music to his listeners. There’s none of the protective cradling of the instrument that some other players present. This sense of generosity also characterises his interpretations, which are open and welcoming, based around good old Russian-style expressiveness and emotional involvement. His height meant that he could get around the instrument with ease, though strangely even he complained about the large size of Stradivari’s cellos and the relative difficulty of negotiating their fingerboards. His long arms enabled free-flowing bow movement and – as he advised his pupils – he tended to hold the bow with his fingers together rather than spaced apart.

Sound

The physical openness of his playing style gave warmth and clarity to his tone – a sound that was creamy yet not cloying, though it can sound more shrill than it perhaps was via the dated and less than ideal technology of most of his recorded legacy. But on the whole, it could be big and spacious for projecting a concerto as easily as it could subsume itself to the more inward needs of chamber music with his colleagues in a piano trio.

Strengths

Piatigorsky always projected a natural sense of a piece of music’s tempo (he was known to fall out with conductors on differences of opinion here) and his phrasing exhibited a similar artless ease that hid a conscious avoidance of archness. He may have been averse to the idea of being a showman, yet his technique had tricks of its own, notably an ease with down-bow staccato and spiccato to match that of his up bow, as seen in his filmed recording of his own arrangement of Schubert’s Introduction, Theme and Variations D968a.

Weaknesses

The cellist was the first to agree that he was not a technical perfectionist with a view to clinical intonation. He was more concerned with conveying the composer’s emotional meaning than sacrificing it in favour of note-for-note accuracy. His style of vibrato has not always been to everyone’s taste, its speed and narrow range arguably being the result of his large build making it difficult for him to use the whole forearm to shape the tone, instead vibrating from the wrist alone. He was very much an ‘old school’ player, maintaining a certain 19th-century freedom of approach to music throughout his career, showing no interest in attempts at period authenticity or editorial rigour.

It should be added that his advocacy of new music was very much geared, especially in later years, towards the more conservatively tonal composers.

Instruments

Piatigorsky relates in Cellist how he made his own first cello out of a couple of pieces of wood, how a later proper instrument got crushed by a drunk in a café and how he came to buy his first decent cello when a generous gift from a rich patron enabled him to purchase a fake Guarneri ‘del Gesù’ for 9,000 roubles. Next came a possible early Stradivari or Amati formerly owned by the Hungarian player Arnold Földesy, then he re-awoke the 1739 ‘Sleeping Beauty’ Montagnana from its slumbers (gaining the instrument as a gift from Alfred Hill). However, its fragility made it unsuitable for modern repertoire so he sought a companion for it and landed the first of his two authenticated Stradivaris, the 1725 ‘Baudiot’; it was later joined by the 1714 ‘Batta’, of which he wrote: ‘Bottomless in its resources, it spurred me on to try to reach its depths, and I have never worked harder or desired anything more fervently than to draw out of this superior instrument all it has to give.’

RepertoIre and RecordIngs

Piatigorsky’s repertoire was wide-ranging but largely serious. He was generally disparaging of show for its own sake and only reluctantly conceded to his managers’ requests to include encore-like pieces in his concert programmes. The concertos of Haydn, Schumann and Dvořák, Brahms’s ‘Double’ and Strauss’s Don Quixote were the mainstays of his Classical–Romantic fare, but he also launched later works himself, including the Walton, Prokofiev and Hindemith concertos, all premiered under his bow. In chamber music, too, he combined classic piano trio and sonata repertoire with new works, partaking in an early performance of Schoenberg’s Pierrot lunaire and being among the first to take to Ravel’s Piano Trio, both in his Berlin years.

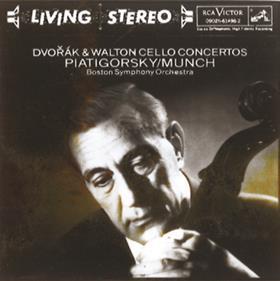

Piatigorsky’s solo discography is not vast, perhaps reflecting the relatively small concerto repertoire available to him, and he is more often to be found in recordings with his great friends and colleagues such as Horowitz, Heifetz and Rubinstein, in collections sold under their names rather than his. Some key works of the cellist’s armoury are notably absent: no complete Bach Cello Suites, for instance, though he had often included such works in recitals. His Beethoven sonata cycle with Solomon is preserved, however. One of his earliest recordings is of the Schumann Concerto under Barbirolli (1934), complete with London Philharmonic oboist Leon Goossens’s unerasable ‘bravo’ at the end. Otherwise, his major stereo concerto recordings, mostly for RCA, were made with American orchestras, the Dvořák and Walton, in Boston under Charles Munch, the Brahms ‘Double’ with Heifetz and the RCA Victor Orchestra under Alfred Wallenstein (1960), and Strauss’s Don Quixote with Reiner in Chicago. However, some of his other earlier mono recordings, such as his 1946 Dvořák with Ormandy and the Philadelphia and a 1951 Brahms ‘Double’ with Milstein, exhibit superior, more secure playing.

These studio accounts have been supplemented in recent years by the resuscitation of some of his radio recordings, including a 1940 Elgar Concerto with Barbirolli and the Hindemith Concerto from 1943 under its composer, highlights of a West Hill Radio Archives set also featuring long-forgotten 78s and unpublished studio takes; and Tanglewood has released a download of a 1953 festival performance of Don Quixote with Munch and the Boston Symphony. Many of Piatigorsky’s classic RCA recordings are in limited supply, and sadly owner Sony Classical doesn’t even recognise Piatigorsky’s name in its online catalogue of artists. But the fruits of the Heifetz– Piatigorsky concerts – an extensive, starry series of largely chamber recordings made relatively late in the two musicians’ careers – are at least available again.

Timeline

1903

Born in Ekaterinoslav, now Dnipropetrovsk, in Ukraine

1918

Becomes principal cellist at the Bolshoi Theatre

1921

Escapes Russia and moves to Berlin

1924

Appointed principal cellist of the Berlin Philharmonic

1928

Embarks on solo career

1929

Makes US recital debut at Oberlin College, Ohio

1940

Settles in Elizabethtown, New York

1941

Becomes head of cello at Curtis Institute of Music

1949

Forms ‘Million Dollar Trio’ with Heifetz and Rubinstein

1957

Heads cello department at Boston University

1962

Settles in Los Angeles to teach at University of Southern California

1976

Dies of lung cancer in Los Angeles

Recommended Recordings

The Art of Gregor Piatigorsky

West Hill Radio aRcHives WHRa-6032, 6 discs plus dvd

The Heifetz–Piatigorsky Concerts

Sony/RCA 545145, 21 discs

Schumann/Saint-Säens: cello concertos/Bloch: Schelomo

Testament SBT 1371

Dvořák/Walton concertos

Sony/RCA living stereo 66375

Strauss: Don Quixote

BSO Classics/Tanglewood (download only)

Brahms: ‘Double’ Concerto (1951)/Strauss: Don Quixote

Sony/RCA legendary performers 09026-61485

Brahms: ‘Double’ Concerto (1960)

sony/Rca victoR Red seal 88697 04605 2 (HyBRid sacd)

Beethoven/Brahms/Weber: cello sonatas

Testament SBT 2158, 2 discs

Mendelssohn/Chopin/ Strauss: cello sonatas

Testament SBT 1419

Ravel/Tchaikovsky: piano trios

Sony/RCA Victor red seal 63025

From they June 2015 issue. Click here to subscribe

No comments yet