Robert (Bob) Lewin wrote The Strad market report for 50 years and was an eminent British collector of String instruments and bows. His nephew, Michael Lewin, remembers his uncle, and how his legacy helps thousands of young musicians around the UK today

Bob was first given a violin by his father at age 12, at the same time as his elder brother. He took to the violin and used it to escape the family business that his father tried pushing him into. He left home at 17 and started playing wherever he could earn a living. It’s believed that he had lessons with Achille Rivarde, who had been a pupil of Wieniawski, and also studied with Sacha Lasserson.

By the time he was 19, Bob was playing in the pit of silent films and leading a small orchestra, as well as playing in the Cinema cafe before and after the showing. He was later Leader of the Wembley Philharmonic Orchestra, where he played solos; he was also the ‘fixer’ for the orchestra that played the Christmas Pantomime at Windsor Theatre, which HM The Queen used to attend, much to Bob’s delight.

Bob also loved to write and began a long association with The Strad and its then editor EW Lavender; he wrote witty, perceptive articles, later contributing a regular report on London Sale activity. With slightly deteriorating hearing he was often found in the front row of Sotheby’s or Christies; he was once overheard, as the hammer came down on a particular lot, exclaiming ‘£7000, for a fake!’

Bob wrote for The Strad market report for about 50 years. Two years before he died, he asked if I would help him to sort out his affairs. He’d lived on his own for much of this time, and his flat was more than a bit dusty! I knew a little bit about Bob’s life and his musical career but he kept a lot secret, including details of his own personal collection of instruments. Keith Wilson, Bob’s friend and a Violist who worked for the BBC, remembers that Bob built up his collection over many years, through Auction houses such as Phillips, Sotheby’s and Christies, as well as a myriad of private deals. He established a close relationship with Sotheby’s and advised over the sale of the Lady Blunt Strad, which achieved a record price at the time.

At Bob’s request, I took him to a lawyer to make some changes to his Will; the lawyer asked him what he wanted to do with his instruments. He refused to answer and there was dead silence! Eventually Bob looked at me and said, ‘You don’t want them, do you?” He didn’t really want to let go of them: he wanted to take them with him! Inspired by my sister, who had worked for the Philharmonia and administered the Martin Scholarship Fund, I asked Bob if the instruments could be used to create scholarships for young musicians who needed help to develop their talent. He thought it was a great idea, and the decision was made.

Read: Stradivari violin ‘Benecke’: Unconventional Beauty

Read: 7 tips on adjustments to get the best out of your instrument

Watch: Luthier Peter Westerlund shares ‘unique methods’

When Bob passed away, the collection itself was not that easy to find, though. Bob had a steel-lined room in his flat in which he kept some of them, but he also had a number of bank accounts all over London. It transpired that he would go to a local bank, open an account and say: “I don’t want any interest, I don’t want any charges, I just want to use your safe to store some of my violins”. To my frustration, there was no list of which banks held which instruments!

Armed with a copy of his Death Certificate, I worked my way round all the banks that I’d identified from scraps of paper and cheque stubs and gradually retrieved most of the boxes, usually containing at least two instruments and, in some cases, up to 15 Bows.

One Uxbridge bank, which held his main account, strongly denied the existence of any boxes, in spite of several letters. But Fiona Bruce (now of Antiques Roadshow fame) had heard of this bloke going round North London banks, looking for violins and boxes. She made a TV piece about my search and even got Nigel Kennedy to play three of the fiddles on film; I believe his interest was piqued because my sister, Vivienne Dimant (Hon.A.R.A.M.) had arranged a Martin Scholarship for him, in his younger days! A Cashier at the Uxbridge branch happened to watch this edition of the ‘Antiques Show’ and remembered the name Robert Lewin; the following morning she went to her Manager and said she was sure there were a couple of boxes in their vault in his name: she found them and informed me; when opened, there was about £70,000 value of violins and Bows inside, all in good condition. This was about a year after Bob’s death; I wanted to sue the bank as I had letters denying their existence – but I was persuaded otherwise.

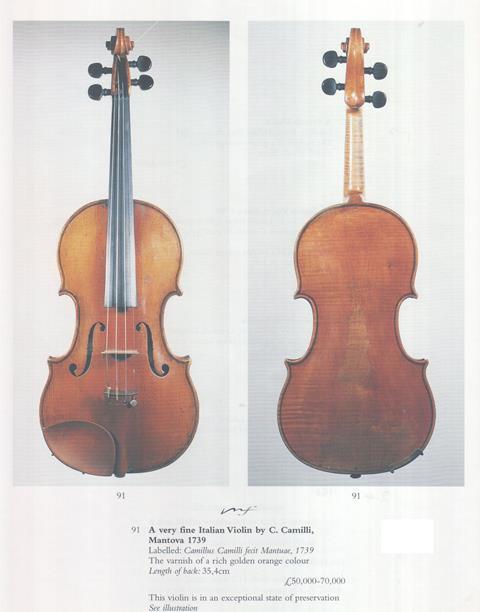

After months and months of searching, the collection included cellos by Giovanni Grancino (1693) and Pedrazzini (1922); violins by Camilus Camilli (1739) Tomaso Eberle (1780) J. Hel (1896) T.E. Hesketh (1898) and L. Bsiach (1895); violas by H. Derazey (1860) and C. Harris (1824). In total, the collection was worth about £750,000 at Probate.

It was the funds from this sale in 1998 that were used to start The Musicas Fund, which later became Awards for Young Musicians (AYM). Since then, AYM has helped thousands of young musicians achieve their musical potential, with funding and other help, and by supporting music education through training, advocacy and research.

We started in 1998 with our Awards programme, helping talented young musicians through Robert Lewin Scholarships. All the young people we directly support have demonstrated financial need, in addition to real, musical talent. We help instrumentalists from low-income families, playing all genres, to realise their potential, enabling them to overcome financial and social barriers in their musical journeys. In addition we now have a growing number of ‘Named Awards’giving families a wonderful way of remembering loved ones, whilst supporting our work.

Over the years, our CEO, Hester Cockcroft has created further, additional and equally important programmes, tackling other barriers faced by these young musicians. ‘Identifying Talent’ trains teachers how to spot and nurture young people’s musical potential; ‘Furthering Talent’ targets and sustains young people’s emerging talent through individual support. Both these programmes have received significant ongoing funding by Arts Council England through Youth Music.

Since 1998 we have directly helped more than 3000 young musicians; several thousand more have benefited from our innovative research and advocacy, resulting from AYM’s independent role in the music education sector, where we’ve led new thinking and action on talent development. Bob would be amazed!

To find out more about Awards for Young Musicians, please visit https://www.a-y-m.org.

No comments yet