Philip Kass takes stock of the violin making industry, and identifies highlights and challenges - aside from the current threat posed by Covid-19

The following are extracts from the cover story in our 130th anniversary May 2020 issue. To read the full article in which stringed instrument expert Philip Kass looks at the future of the industry, click here to subscribe and login. The May 2020 digital magazine and print edition are on sale now.

As far as violin and bow making are concerned, we are now living in a golden age, and perhaps have been since the late 1990s. Violin making has shifted from a regional craft to a truly global one. In Stradivari’s day, the craft was highly concentrated in a few regional centres, mostly in continental Europe, and supplied the needs of a small part of the Earth’s population, which then numbered perhaps 600 million. Today, with a global population of around 7.8 billion, and with many more than half of these individuals having access to and awareness of stringed instruments, that market has grown almost logarithmically. The quality of new instruments and of training in lutherie is at a predictably high level, as are the skill sets of those now drawn into what is a far more lucrative profession than it was in the past. Indeed, one can say that today’s excellent violin and bow makers outnumber all of the great masters of the past put together. Furthermore, from a standpoint of skill, the quality level of today dwarfs that of any time in history….

……

Professionals need to make a living through their music, but as time has gone on there seem to be fewer opportunities to do so. In the US, only the largest twenty or so orchestras pay their musicians a salary superior to or commensurate with the national average amount. At the same time, the means of paying for musical services are increasingly in flux, as traditional market structures prove unsustainable and viable replacements are still in development. The professional market, therefore, is far less stable than we might think.

As far as instrument prices are concerned, though, the professional player remains a prominent presence in their determination. If players’ ability to buy instruments declines, then so will the prices – except that the other part of the market has seen no such limitations on their ability to buy fine old instruments. In the US it is seen as the issue of ‘the 1 per cent’ versus ‘the 99 per cent’. Prices at the top can be driven by the 1 per cent, but the strength of the market long-term comes from the 99 per cent. Will the market remain stable under these circumstances? This remains to be seen.

Another issue could be the matter of commercial production. Modern factories in China have been highly efficient in producing good instruments, but the very fact that we still use 400-year-old violins is a reminder that the shelf life of a violin is measured in centuries rather than years. Could we get to the point at which there are more violins in existence than there are people who want to use them? We have already seen something of that effect in the market for pianos, which for many fine old brands has rendered their new work less valuable than firewood. We must see whether any such situation influences the violin trade.

-

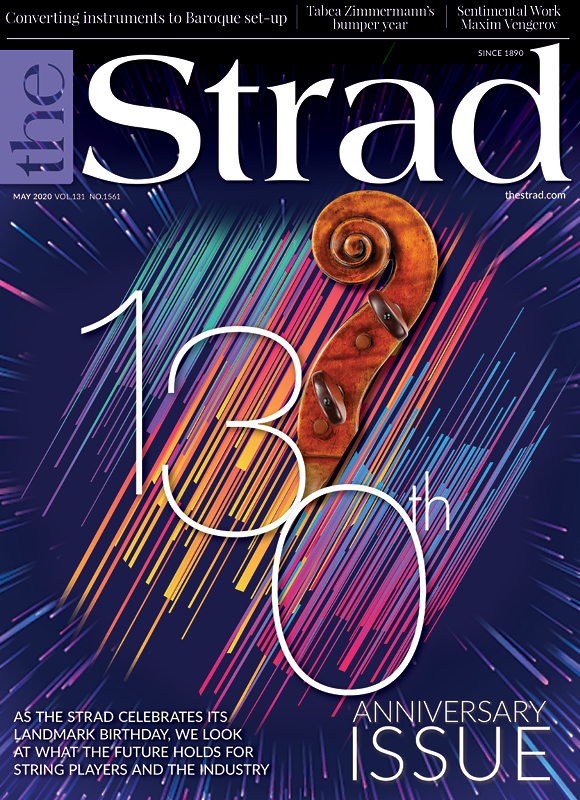

This article was published in the May 2020 130th Anniversary issue

The Strad marks its 130th anniversary with a look at the future of string playing and the violin industry. Explore all the articles in this issue.

More from this issue…

- A look at the future of string playing and the industry

- Violist Tabea Zimmermann on her bumper year

- Converting an instrument to Baroque set-up

- Making a career in music therapy

- How luthiers can avoid repetitive strain injury

Read more lutherie content here

-

No comments yet