Tim Homfray travels to the northern coast of Spain to experience a unique gathering of young chamber players and master musicians

Discover more Featured Stories like this in The Strad Playing Hub

Read more premium content for subscribers here

Santander, perched by the sea on the northern coast of Cantabria, Spain, is often rainy in July – or so I was told. Not when I was there, it wasn’t. There was a baking sun and a cloud-free sky, and wherever I went, Santanderians – if that is the word – were heading for one of its many beaches, loaded with mats and bottles of water.

July is also the month of Santander’s Encounter of Music and Academy (Encuentro de Música y Academia de Santander), an annual event (this year running from 1 to 23 July) in which young musicians from conservatoires all over Europe gather for masterclasses and concerts. The standards are high: most of these individuals are in the foothills of professional careers and some have awards and competition successes on their CVs. That combination of tutelage and performance is the raison d’être of Encounter. An extra edge is added for the players by the unknown repertoire they will be given to learn and perform in only a few days with people they have never met before – unknown both because the musicians don’t know what it will be and because some of it will be little known to anyone.

Read: Stepping up: Postcard from Munich

Read: Masterclass: Johannes Moser on Brahms Cello Sonata no.1 op.38

Explore more Featured Stories like this in The Strad Playing Hub

Read more premium content for subscribers here

The concerts are spread among a number of venues, but they are centred on the two halls in the Palacio de Festivales de Cantabria, a sloping rectangle of a building on the seafront. The first concert I went to (14 July), in the smaller hall, the Sala Pereda, opened with Mozart’s Duo in B flat major K292 for bassoon and cello, with ensemble a little untidy but featuring some nifty cello playing from Máté Tomasz. Penderecki’s Duo concertante for violin and double bass was entertaining stuff that put both players through their paces, with some high bass writing for Akseli Porkkala, and violinist Reika Sato nipping up and down in double-stops, bow ricocheting away. In Prokofiev’s Overture on Hebrew Themes, there was good, keening playing. Sato returned for Stravinsky’s Soldier’s Tale Suite in its arrangement for clarinet, violin and piano, with dry, sardonic playing in the ‘Marche du soldat’ before she really hit her stride in the three dances of movement four, bending notes and showing a hint of swing.

Miklós Perényi coached Brahms’s first cello sonata from memory (which kept the accompanist on his toes)

Encounter was founded in 2001 by pianist Paloma O’Shea, who had previously founded the Reina Sofía School of Music in Madrid and the Albéniz Foundation, under whose auspices the Paloma O’Shea Santander International Piano Competition has been running since 1972. For most of its existence, Encounter has been under the artistic directorship of violinist and conductor Péter Csaba. It was he who developed its format of orchestral concerts at the start of the festival and then lots of recitals and chamber music, most of it chosen and allocated by him. He decided early on that all the applicants should be auditioned in person, something which he does himself, visiting conservatoires all over Europe. This year there were more than 60 auditionees, including string, wind and brass players, pianists and singers. It is an intensive process, in which Csaba might hear everyone in a couple of days.

The chosen ones are provided with accommodation, food and a bit of spending money – all paid for by Encounter. The string players invited this year received masterclasses from violinists Christoph Poppen and Zakhar Bron (an old Santander hand), violist Nobuko Imai and cellist Miklós Perényi.

The masterclasses were private, but the organisers kindly allowed me to attend a couple of them. I sat, trying to be an invisible mouse, as Bron worked on Tchaikovsky’s Valse-Scherzo, discussing minutiae of bowing and phrasing, a note not given its proper length, a pause that is ‘tradition not Tchaikovsky’. To work on a double-stopped passage he invented a little exercise, and poked the student’s fingers. He constantly demonstrated the use of the bow. From there I moved to see Perényi, who coached Brahms’s First Cello Sonata from memory (which kept the accompanist on his toes). He too worked away at the finer points of bowing, of connecting and separating notes, and spiked the room with laughter.

Read: ‘I was falling in love with chamber music all over again’ -Postcard from Napa Valley

Read: Double Bassist magazine: Nights in the gardens of Spain

Explore more Featured Stories like this in The Strad Playing Hub

Read more premium content for subscribers here

This was a polyglot morning. Bron, originally from Kazakhstan, taught a Japanese student in English, with smatterings of German and Russian; Perényi, a Hungarian, finished with one student in English then switched to German for the next.

The professors also performed in the concerts. At the second one I went to (on 15 July), Perényi played Schubert’s Arpeggione Sonata with piano student Tom de Beuckelaer in attentive collaboration. The first movement was mellow, with a subtle glow to the sound, and the opening melody of the second was shaped and phrased as if all in one bow. The final Allegretto was airy and dancelike, rhythmically perfectly centred. The concert ended with Vaughan Williams’s early Piano Quintet in C minor featuring piano professor Claudio Martínez Mehner and student participants on the violin (Alexey Stychkin), viola (Felipe Manzano), cello (Juliet Wolff) and double bass (Andrés Arroyo) – and I doubt that any of them had previously been familiar with the work. The first movement had good Brahmsian relish, with beefy octave passages, and there was fine playing from each musician in turn, both here and in the Andante. They were stylish in the strange sound world of the finale, welding its disparate sections into a cohesive whole. Although only a few days old, this was an excellent chamber ensemble.

The following night, Imai performed Rebecca Clarke’s Viola Sonata with pianist Aidan Mikdad, bringing swathes of flowing lyrical expression to the first movement and nimble elfin dance to the second. In the third she was intimate, confiding, her tone warmed by generous vibrato before the ecstatic final passage. After her came a quartet led by violin professor Poppen in Mendelssohn’s Second String Quartet (Hani Song, violin; Toby Cook, viola; Tomasz, cello). This blossomed as it went on, becoming a full-on contrapuntal drama. Each player coaxed the fugue subject of the second movement elegantly to life. In the Intermezzo there was exquisite simplicity from Poppen, who then propelled the finale forward on a surge of energy. The final work, an arrangement for nonet (five wind and four stringed instruments) of Brahms’s Serenade no.1 in D major, was full of finesse and youthful high spirits, with string players Phoebe White (violin), Ionel Ungureanu (viola), Jonathan Reuveni (cello) and double bassist Porkkala.

Later, as I returned to my hotel, I was greeted by a huge firework display on the beach. It wasn’t for me, sadly, but for the Virgen del Carmen, the patron saint of fishermen, with great waves of exploding colours, almost overwhelming, and at the end immensely loud. It was quite a send-off.

Read: Music by the sea: Postcard from Cornwall

Read: That festival feeling: Postcard from Odense

Explore more Featured Stories like this in The Strad Playing Hub

Read more premium content for subscribers here

-

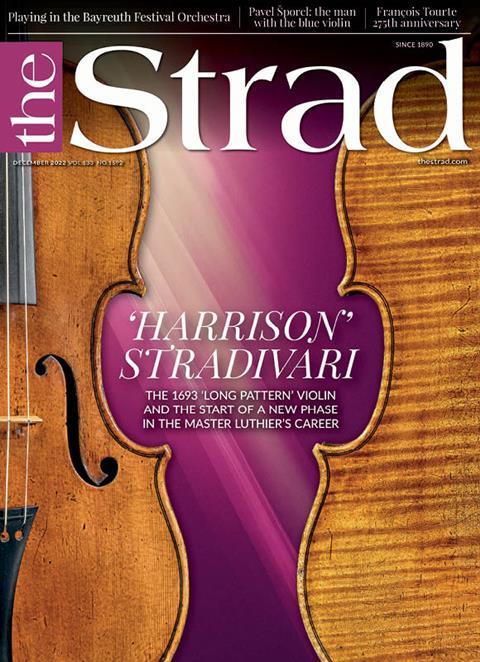

This article was published in the December 2022 1693 Antonio Stradivari ‘Harrison’ violin issue.

A prime example of the master luthier’s ‘Long Pattern’, it used to be the principal performing instrument of Kyung Wha Chung. Andrew Dipper takes a closer look at the violin. Explore all the articles in this issue

More from this issue…

- 1693 Antonio Stradivari ‘Harrison’ violin

- Pavel Šporcl

- Bayreuth Festival

- François Xavier Tourte

- Pablo Ferrández

- Felix Yaniewicz

Read more playing content here

-

![[1st prize] Poiesis Quartet in round 3 (2)](https://dnan0fzjxntrj.cloudfront.net/Pictures/100x67/1/9/5/41195_1stprizepoiesisquartetinround32_547631.jpg)

No comments yet