Students, amateurs and professional makers all came together at this year’s Lutherie Day for talks on anything violin-related. Christian Lloyd went along

Discover more lutherie articles here

Read more premium content for subscribers here

Newark-on-Trent is one of those English towns that feels as though the last 50 years never happened. Its rows of half-timbered houses, cobbled market square and the striking remains of a twelfth-century Norman castle all give the impression of a place unencumbered by the cares of the 21st century. It could be said that it’s an ironic kind of location for the country’s best-known violin making school, given the fast-paced and ever-changing nature of the luthier’s craft – as was much in evidence at Newark’s annual Lutherie Day on 3 May this year.

Lutherie Day has been running almost every year since 1999, when it was set up by Newark tutor Robert Cain. It was conceived as a chance for professional violin makers, amateurs and students to get together to compare notes and inspire each other, also including various lectures, presentations and rare instruments for study. Cain ran it almost single-handedly until 2019, when Covid forced a two-year break. Since then it has been organised by Helen Michetschläger, this year with the help of Tim Southon and Nicole Terry. As she told me: ‘One of our aims with Lutherie Day is not to pack the lectures too tightly so that there’s time for people to circulate and chat’ – which also gave the attendees a chance to visit the various traders’ tables, take a free copy of The Strad and examine our own latest books and posters.

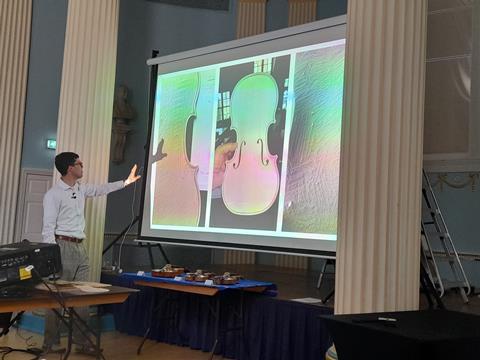

This year’s lectures kicked off with a short tribute to the late Charles Beare (who had passed away just a week before) by luthier Mark Robinson. Beare had been instrumental in the creation of the Newark School of Violin Making back in 1972, and made a point of visiting the school at least twice a year, often bringing a fine instrument for the students to examine. ‘Anyone here who had anything to do with Newark owes a debt to Charles,’ Robinson finished, to a large round of applause. This was followed by the first of the day’s lectures, in which French luthier Paul Belin gave an introduction to CNC routing and CT scanning. ‘When I was studying here almost 30 years ago, there was hardly any technology,’ he began. ‘All we could do was photocopy books and posters from The Strad. Now things are better.’ He demonstrated how to design a fingerboard (the easiest shape to mock up), recommended Fusion 360 as his favourite design software, and then showed how a more complex shape such as a milled patch could be created.

‘Anyone who had anything to do with Newark owes a debt to Charles Beare’ – Mark Robinson

Belin’s presentation led to some interesting questions on the ethics of using this technology: when does an instrument stop being ‘hand-made’ and more ‘machine-made’? Belin saw no ethical challenges, while Florian Leonhard made the point that when he started learning at the Mittenwald School in 1982, ‘we weren’t even allowed to use a bandsaw – we had to do all the cutting by hand.’ Outside the hall, a comparison was made with music students learning repertoire by watching Heifetz performing on YouTube, rather than studying the score – should luthiers also learn the skills of the trade before resorting to CNC machining?

Philip Ihle was the next speaker, on the subject of making copies. He divided them into three: making a copy of an old instrument as it looks now; attempting to make it as it would have looked when it left the maker’s workshop with no wear or antiquing; and finally, what he called ‘DNA Strad’: ‘understanding the elements of beauty that unify Cremonese violins, and use those elements freely in my own work’. ‘We’ve made between 80 and 90 instruments in my workshop over the past eleven years,’ he said, ‘and the focus has shifted from making exact copies to using these elements. I’m also now looking at how my instruments will develop: will there be a definite style, or will I always just be chasing the Cremonese makers that my clients and I love so much?’

For the first kind, Ihle gave the example of a c.1600 viola by Antonio Brensi, which he antiqued using soot, rosin and turps – which, he recalled, gave an unhealthy atmosphere to the workshop. Secondly, he recalled a client who commissioned a copy of the ‘Lord Wilton’ Guarneri, but insisted it not be antiqued. Observing that ‘del Gesù’ used long knife cuts, he said: ‘One of the aims for me was to have as few pieces of wood come off as possible. If 5,000 bits come off, it’s better than 20,000.’ Lastly, he gave examples of finding his own personal style, such as when he spent five weeks last year carving a bucketful of 70 scrolls. ‘It was both an efficient and a personal way to do it,’ he explained. ‘If I carve one scroll for an instrument, it’s less individual and more of a copy. If I do ten scrolls, my own hand shows more, and I also feel I’ll have improved as a scroll carver.’

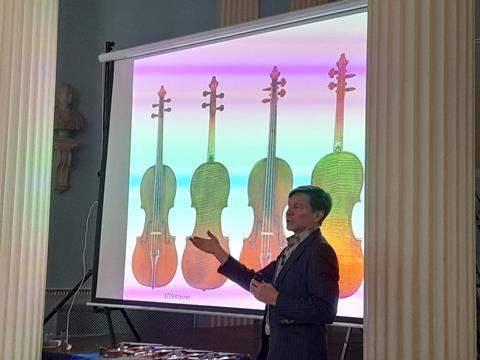

Next up, Florian Leonhard gave a fascinating lecture on the instruments of Guarneri ‘del Gesù’ who, we learnt, also cut his scrolls in batches and only later fitted them to each instrument. Leonhard made an interesting observation about the wood used in Cremona in the 1720s: even Stradivari was forced to use less beautiful wood for a time, but suddenly in the 1730s, ‘del Gesù’ had superb, deeply flamed wood that looks extremely like that used by his brother, Pietro Guarneri of Venice. Was it possible that ‘del Gesù’ had access to excellent wood from Venice, using his familial connections? The theory might be worth investigating further. At the end of Leonhard’s presentation he invited the listeners to examine four fine instruments he brought with him: two by ‘del Gesù’ from 1732 and 1738, a ‘Long Pattern’ Stradivari from 1695 and another Strad from 1731.

The final lecture of the day was given by Mira Gruszow and Gideon Baumblatt. It was divided into two: first, they gave an account of an experiment for prematurely ageing the wood of an instrument that was almost finished. ‘In some old instruments, you can observe how the long arch has become flatter at the midpoints of the upper and lower bouts,’ they said. This method of ageing the wood by placing it in a UV cabinet, with the instrument under string tension, might help to lessen that effect – although further research is required. Secondly, they discussed the benefits and challenges of working together as a couple: for instance, that all decisions could be made together, but that the collaborative system might hinder any risk-taking or experimentation.

Going by the discussions outside the main hall, it seemed that the presenters had done their job and prompted some animated conversation, not least about the working life of ‘del Gesù’. The current students at the Newark School also deserve praise, since so many had turned up to help behind the scenes and make sure the day went as smoothly as it did. Next year’s event is scheduled for 2 May 2026, and it’s a safe bet that it will provide some stimulating talk, and boundless inspiration for the assembled throng.

Read: No degree course for Newark School of Violin Making students beginning in 2025

Read: Newark School of Violin Making: The early days

Discover more lutherie articles here

Read more premium content for subscribers here

An exclusive range of instrument making posters, books, calendars and information products published by and directly for sale from The Strad.

The Strad’s exclusive instrument posters, most with actual-size photos depicting every nuance of the instrument. Our posters are used by luthiers across the world as models for their own instruments, thanks to the detailed outlines and measurements on the back.

This third volume in The Strad's Great Instruments series brings together the finest scholarship, research and analysis by some of the world’s leading experts on stringed instruments.

The Canada Council of the Arts’ Musical Instrument Bank is 40 years old in 2025. This year’s calendar celebrates some its treasures, including four instruments by Antonio Stradivari and priceless works by Montagnana, Gagliano, Pressenda and David Tecchler.

![[1st prize] Poiesis Quartet in round 3 (2)](https://dnan0fzjxntrj.cloudfront.net/Pictures/100x67/1/9/5/41195_1stprizepoiesisquartetinround32_547631.jpg)

No comments yet