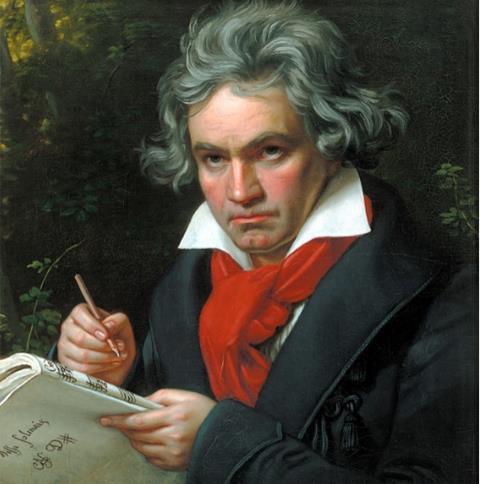

Beethoven has been denied his year of celebration by the coronavirus pandemic. But, writes Toby Deller, his ‘Heiliger Dankgesang’ is an emblem for the current crisis

With barely another major composer anniversary as competition, Beethoven looked to have centre stage for himself in 2020. But he has been swept off along with all of us, just as Patricia Kopatchinskaja forewarned in her 2016 project Bye Bye Beethoven.

There were some who argued, as his 250th anniversary year approached, that a twelve-month moratorium on performing Beethoven would have been a greater gesture of recognition than dedicating whole series and festivals to him. What better way, so the reasoning went, of understanding the importance of his music than by observing the hole left by its absence? And anyway, we play Beethoven all the time; is more of the same really such a special tribute?

These arguments are academic now - or at least for seven years anyway (Beethoven died in 1827). Fate has seen to it that a de facto moratorium on public celebrations is what we have. Yet once the current pandemic has subsided and it is time to put together the soundtrack to this episode, there may still turn out to be a place for Beethoven.

It was after a serious illness that he wrote much of his string quartet in A minor, op.132, its slow movement known as the ’Heiliger Dankgesang’ following his description for it in the score: ‘Holy song of thanks of a convalescent to the Deity’. An acute intestinal condition in April 1825 had interrupted the writing of the quartet, leaving him weak for some time afterwards. ‘There can be no doubt that my digestion is terribly weakened,’ he wrote to his doctor on 13 May, asking for stronger medication and expressing disgust at the beer where he was staying. ‘In fact my whole system, and, so far as I know my own constitution, my strength will never be recruited by its natural powers.’

Recovering all the same, he was able to finish the quartet by July, with the ’Heiliger Dankgesang’ as its centrepiece. The movement, as if to echo his own experience, alternates prayerful slow sections with gladsome passages marked, in German, ‘Feeling new strength’. Perhaps because the gravity of his illness was so fresh in his mind, Beethoven was moved to write this intensely felt movement and to dedicate it as he did. The experience certainly seemed to spook him. Or perhaps he was simply keeping his side of the bargain, made with the Deity while he was suffering – who hasn’t offered promises from their sickbed in exchange for a rapid cure?

Read: After Corona, pay inequality among musicians will be unsustainable

Read: Is Covid-19 killing off classical music’s cult of perfection?

Read: Perhaps it’s time to practise in front of an audience

Speculation aside, it is rare for a piece of music to have illness, as opposed to death, as its subject in quite such an open way. Smetana’s first quartet comes to mind, although the tinnitus he depicted there proved irreversible. Beethoven’s work, by contrast, deals with recovery - and a musician’s recovery to boot. In this light, the ’Heiliger Dankgesang’ is something of an emblem for the current crisis, providing an entire musical community, laid up by the arrival of the pandemic, with food for thought.

That musical community and its culture are not yet at the convalescent stage, however. It is too early to be giving thanks and moving on, even if the signs of recovery are there. But we surely have a responsibility between us to do more on behalf of our fellows than simply to wait and hope things return to the way they were before.

Some of the remedies – those addressing weaknesses in the structures and practices of musical culture – will need to come from within the community itself. Others could be provided by wider society: the introduction of a universal basic income, for example, so that everybody, musician or otherwise, is automatically supported in hard times and good. Others, focusing, for instance, on the role of the artist in society and the realistic and equitable funding of artistic work, will involve an in-good-faith dialogue between the two.

As for Beethoven, he lived only two more years after his 1825 glimpse of mortality, the damage having no doubt been already done. It is to be sincerely hoped that the current pandemic does not prove terminal for us. We have Beethoven’s op.132 to remind us of what we have been through and what we stand to lose. While it may seem unjust and punitive that our industry is bearing the brunt of enforced shutdown worldwide, that is all the more reason to look at ways of ensuring we are both better able to weather a recurrence and are less complacent about the threat of other possible traumas. More of the same is not always for the best.

2 Readers' comments