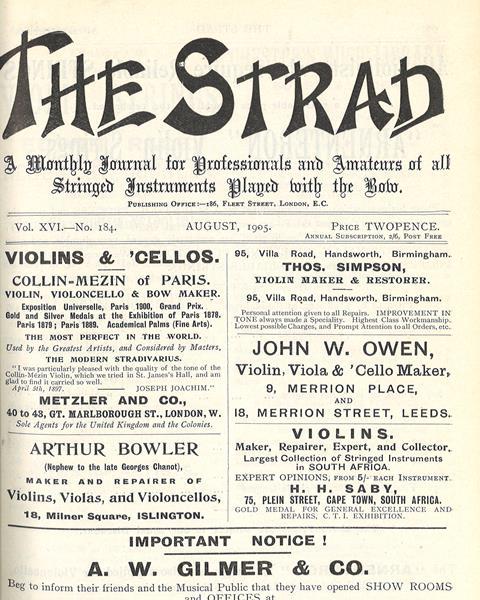

As the new school year beckons, an article from The Strad, August 1905, offers some sage advice to parents thinking of violin lessons for their children

There are many parents, at this time of year, planning to place some little member of the family in the hands of a violin instructor when the cool days of autumn come round once more. These parents are probably asking themselves, as well as their friends, many anxious questions which admit of no immediate solution, chief among which it is safe to say, are the two that follow: (1) Has my boy (or girl) genuine talent for the violin? (2) Who is a capable instructor and safe musical guide?

The first question time alone can solve. It is practically unanswerable during the period when anxious parents are most eager to learn something definite concerning their child's real aptitude and musical gifts. Mere aptitude too frequently is mistaken for actual talent: and often, too, the aptitude proves to have such serious limitations that after the groundwork has been laid it ceases to be a factor of any importance whatsoever.

'But how does real talent manifest itself in a young child?' asks the anxious parent. To attempt to answer such a question would be folly. It is an exceedingly difficult matter to differentiate between mere aptitude and genuine musical gifts without a certain amount of training and experience. The child that evidences in a hundred different ways its fondness for the violin before actual work has begun, may prove, in the end, to be wholly unfitted for a musical career. And, on the other hand, where it is sometimes difficult, in the beginning, to discover a sufficiently strong leaning towards the instrument to warrant the teacher in designating the tendency as true talent, watchfulness and careful training prove the existence of unsuspected talent.

It will therefore be seen that the early stages of a pupil's development necessarily throw no clear light on what lies dormant within him. The first years are, as a rule, purely experimental ones: though it does infrequently happen that a pupil gives unquestionable evidence of a high order of talent long before he has had the opportunity to demonstrate the possession of it by uncommon instrumental skill. Exceptions of this kind, however, are very rare; and few of our teachers are fortunate enough to find one such gifted child during the years of their pedagogic struggles.

As to the second question, much has been said and written by others as well as by ourselves. Teachers, like poets, are born, not made. Few have the keen instinct, the common sense, and the requisite knowledge worthily to be termed fine instructors. Few are temperamentally fitted for the arduous life of a teacher, though an untold number have adopted the vocation as, seemingly their best means of earning a livelihood.

To choose for the beginner a thoroughly competent teacher is obviously a delicate and difficult task. The majority of parents, however, seriously increase this difficulty through desire to obtain instruction at the elate possible expense, and through their ignorance of the vital importance of building on a solid foundation. It does not seem to be generally appreciated that the beginner requires the very best instruction procurable; nor is there wide recognition of the fact that the teacher's services to the beginner are such that he would be justified were he to demand from him a higher rate for tuition than from an advanced student. Most parents on the contrary, imagine that the beginner may safely be placed in the hands of almost any player of the instruments; and that a 'high-pitched teacher' should not be thought of till the pupil is far advanced in the art. Everywhere such manifestly absurd reasoning is found to prevail; and parents discover, often too late, the unwisdom of their economy.

Give the beginner the best instruction obtainable. This is both common sense and economy. And do not expect wonderful things of the child that has had a few terms of instruction. Three, four, even five years are required for the learning of trades which require no special gifts. On such a basis of calculation, is it possible to determine the number of years in which the beginner should be able to pass from his first crude experiments to high, artistic achievement?

From The Strad, August 1905. You can access the entire archive here.

No comments yet