Anne Inglis gives her thoughts on cellist Claire Oppert’s book detailing her experiences of how music can transform the lives of dementia patients and autistic children

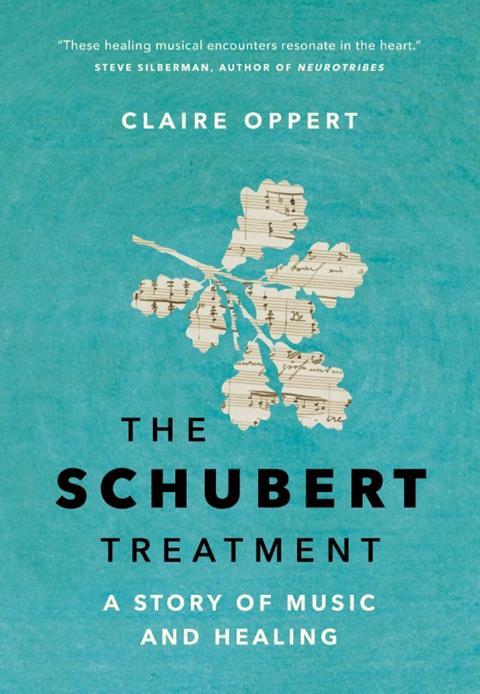

The Schubert Treatment: A Story of Music and Healing

Claire Oppert

Translated by Katia Grubisic

216PP ISBN 9781778400803

Greystone Books £16.99

This comforting book, a slim and elegant publication, falls into a few parts. It opens by addressing the effect music has on dementia in a care home setting; it then moves on to reveal author Claire Oppert’s interactions with autistic children; and finally there are several thumbnail sketches about patients at the end of their lives relying on palliative care. Interspersed are snippets of Oppert’s life story, notably on her years as a cello student in Moscow.

Intimate, brief portraits of people in areas of medical distress are shown to receive comfort from one-to-one musical interactions. There is a clear narrative thread through the series of short chapters as the author, a professional cellist, discovers the effect of musical themes that respond to individuals’ needs and reactions.

Structural links, with the exposition, development and recapitulation of Schubert’s Piano Trio in E flat major, Andante, are used to signpost the beginning, middle and end of Madame Kessler’s story – one of the longer items – and introduce the composer of the title, where a few bars of the theme result in an immediate subsidence of pain as she undergoes a medical procedure. The nurses call this ‘the Schubert treatment’ and the phrase is then adopted for its powers of healing through music.

After turning off the television as her first task on walking into a care home (how we’ve all longed to do this), Oppert is recognised by the dementia patients, and many of them subsequently (it could take many sessions) achieve calmness and retrieve forgotten memories and their self-respect through listening to whatever music might trigger a positive reaction, from the classical canon to folk, jazz, pop and Piaf. The passage of time is marked by the presence of an oak tree outside the window and its seasonal changes, in a subtle and affecting touch in the poetic narrative.

Within the short memoir are Oppert’s elegantly written encapsulations of patients’ transformative responses to her interactions. After the dementia cases, she turns to autism and the influence of her mentor Howard Buten, who tells her not to read about autism, just to respond. Finally there are many pages on the effects of musical extracts on patients nearing death, mostly through cancer, and in several instances enabling a good death. There is no prurience, simply empathy.

On reading this book for the first time, I bought a copy and sent it to some dear musician friends, where the wife of the partnership has early onset dementia. He pronounced it ‘consoling’. On re-reading the text I was alert to the slightly random nature of the experiences. But as a document of the extraordinary power of music to transform lives, even at the end, it cannot be faulted, and I would recommend it as a source of hope to anyone who is affected by life-limiting conditions.

ANNE INGLIS

No comments yet