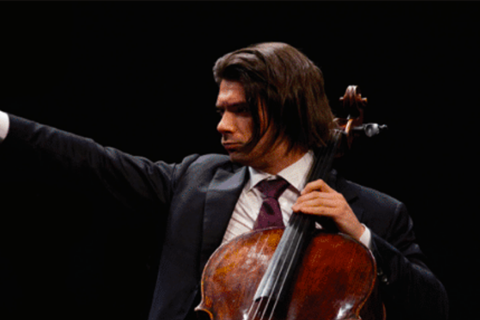

The French cellist finds a whole universe of sound in Schumann’s Adagio and Allegro and the op.73 Fantasiestücke – as well as huge scope for experimentation

Robert Schumann’s three Fantasiestücke of 1849 are both fascinating and paradoxical. I first heard them, and started to practise them, when I was very young because they’re relatively easy to play – but extremely difficult to play well.

As with playing the Bach Cello Suites, I understand them more every time I go back to them, and I find a deeper layer with each passing year.

Schumann’s musical universe is so complex, and those three pieces embody in miniature almost the whole gamut of emotions: humour, craziness, fire, doubt, tenderness – you can just about name any musical character and find it within those works.

I think those layers correspond with my own development as a musician. I know the Fantasiestücke really touched me when I was younger but now they’re more linked to my personality and life experiences.

Talking about them with my students, I’ve noticed that some people will use words to define the meaning for them; others use colours to evoke an atmosphere they can relate to. For me, making music is like watching a movie without the screen in front of me: images appear in my mind and become the emotional bridge to my soul.

The first piece, for example, is so delicate that it’s hard to find the right character for the first phrase. There needs to be both tenderness and melancholy, but also an air of dreaminess. It’s all a question of balance. In addition, I know that I’m on stage in order to transmit Schumann’s testimony to the audience; but I can only do so through my own soul.

What I still find unbelievable is that Schumann wrote these pieces, and the Adagio and Allegro, in less than a week. I sometimes say to my students that the frenzy of composition comes through in each piece: when looking at the score you can see how his pen was just following whatever his brain was telling him. It goes so fast you can almost feel the music flowing on to the page.

The Adagio and Allegro has a similar kind of quality, but with a different kind of character to it. You can tell it was originally written with the horn in mind, which makes it tricky to practise. I had to work on it for a long time to get this horn-like character and can still spend hours on two bars of Schumann, trying to find the right bow speed and asking myself if it’s what I really want to hear.

Most of the time, students are satisfied with their interpretation quite quickly, and stop looking for different ways of doing things.

It’s ironic that Schumann wanted to write something that amateurs would be able to play! These amateurs would definitely have had to have been exceptionally good musicians. If you’re a student the best way to practise these pieces is, first of all, to take pleasure in the music, which will help you to understand what the composer wanted in the first place.

Secondly, be prepared to experiment with all the different colours Schumann enables you to find – like a painter with a palette, you have the ability to mix them together to create an infinite variety of hues.

Thirdly, keep asking yourself: is this what I want? Most of the time, students are satisfied with their interpretation quite quickly, and stop looking for different ways of doing things. Often they rely on the bowings and fingerings in the score without thinking: if I used this different bowing, perhaps I could express myself this way instead, or using this vibrato might carry the emotion better from one note to the next.

Schumann’s cello pieces are perfect for this kind of experimentation, and can help all cellists to find their own voice in the music.

INTERVIEW BY CHRISTIAN LLOYD

No comments yet