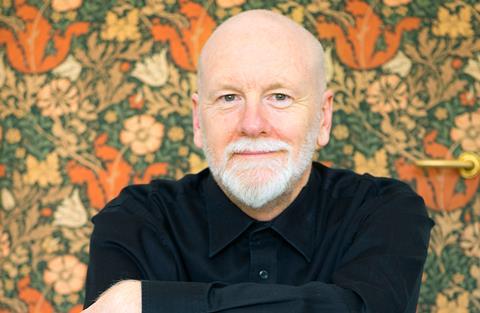

Australian composer Brett Dean speaks to The Strad about his 2018 Cello Concerto ahead of The Ivors Classical Awards, where it has been nominated for best orchestral composition

Discover more Featured Stories like this in The Strad Playing Hub

Ahead of The Ivors Classical Awards results on 14 November, Australian composer and violist Brett Dean speaks to The Strad about his 2018 Cello Concerto, which has been nominated in the awards’ best orchestral composition category. The work was commissioned by a wide range of orchestras including the Sydney Symphony Orchestra, who premiered it in 2018, the Berlin Philharmonic (where Dean worked as a violist for 15 years), the New York Philharmonic and London Philharmonic Orchestra, and under conductors including Simone Young, Marin Alsop and Daniel Harding. Dean discusses the process behind writing the piece, why it is one of his favourite compositions yet, and his and the work’s special connection to its performer, German cellist Alban Gerhardt.

How did the Cello Concerto come about?

The instigator was Alban Gerhardt, principally. He was staying with us in Melbourne around 2008, playing with the Melbourne Symphony Orchestra, and in an interview he said that I was writing him a cello concerto. We’d talked about it as a possibility, but he bravely put it out there in the press and I thought, ‘Well, there you go, that’s one way of going about it!’ Then when it came to it, we were able to get these wonderful orchestras on board.

The other component was that it grew out of a piece for solo cello that I’d written in 2014 called Eleven Oblique Strategies. And already there I showed the piece to Alban, and he was incredibly helpful in checking it out.

Tell me about this solo piece that the Concerto is based on

The solo piece is based on a concept that was formed by Brian Eno and a German visual artist called Peter Schmidt. They were both noting down thoughts, aphorisms, sayings and small triggers on cards and had this deck in their studios. If they felt stuck or needed a jolt, they would take one of their cards. It might be things like, ‘You are sitting alone in a dark room,’ or ‘Build bridges and burn bridges.’ Things that were suggestive and not specific. They eventually made a deck of cards and I chose eleven of them and built the solo cello piece around them.

It was a fascinating experience to then build it further into a concerto. It had this organic way in which the role of the orchestra evolved around the solo line, rather than pitting it against the orchestra like in the traditional, heroic-combative concerto form. It’s surprising how tenacious that model has remained, even from composers you’d expect would blast it open. I think it has a lot to do with the drama of having this single person embodied in an instrument. I always think, because I’m a cricket fan, it’s like going out to open the batting in a test match. There’s an opening tutti, that’s the warmup, and at some point, someone might hit the first boundary and that’s the soloist’s statement. But this Cello Concerto doesn’t follow that at all. And it’s the freedom that I felt in getting furthest away from those conventions that I felt most pleased about.

It also felt quite exploratory. For example, it was the first time I ever wrote a part for Hammond organ. I have no idea why that was, except that I just knew it was a sound I wanted to explore. It has quite a diverse, colourful bed of textures against which the cello unfolds its ideas. The piece is also actually quite tuneful, something that for some contemporary composers would almost be an insult!

What are the similarities and differences between the Concerto and the solo work?

It’s similar material but in the Concerto it’s burst open. Their opening material is actually identical, but from thereon, the dimensions changed because the ideas were picked up by quite a big orchestra. It felt natural to let these ideas ripple through this whole organism. So although the motifs are recognisably the same, you might have shrill woodwinds shrieking, or at some point quite a lot of percussion.

The piece unfolds in one unbroken sweep. It has energy shifts, but otherwise it’s all fairly organic. This plays nicely into the fact that Alban is playing it by memory and can seem to dart off in different directions as if he were improvising. In that way, it’s like the solo piece, where you’re pulling a card out of the pack.

How is Alban’s playing unique and how does it suit this Concerto?

He has this extraordinary ability to internalise what he does. Famously that results in him playing these pieces by memory, which is such an unusual and extraordinary feat nowadays for brand new pieces. It was quite remarkable to see him in those early performances carry the piece off with such panache, and all from memory. It brings a familiarity that he then has with what’s around him, because he’s so dependent on aural cues. It heightens the chamber music aspect of it.

What is it about the cello as an instrument that you enjoy writing for?

I love the cello. Perhaps if I had my time over it’s an instrument I would like to play myself. That said, the viola has been good to me! But one of the earliest pieces I wrote was a piece for the Berlin Philharmonic’s 12 Cellists. It was then that I realised just how magnificent an instrument it is. This massive range in the depths of the C string and then to go right up into the violin’s range. And, like any string instrument, it’s incredibly fragile and delicate, while having a magisterial sweep about it.

The piece has had so many performances with some of the world’s leading orchestras and conductors. How do you feel it has grown since its premiere?

It’s always a familiarisation process. Now, Alban knows which bits need attention for his sake. There’s one big tutti section near the end that does need a bit of particular shaping so it’s not just a lot of loud stuff, that has been interesting to finetune each time. I’m especially pleased that even though there’s a lot going on in the orchestra, it remains transparent. And the process of morphing this solo piece, which is only about ten minutes long, into a larger concerto, was a very spontaneous and happy experience. One of the pleasing things about this nomination is it’s a piece I’m especially proud of. And you do get your own favourites as a composer, and this is one of my very favourites.

Read: Brett Dean on his journey from Berlin Phil violist to full-time composer

Discover more Featured Stories like this in The Strad Playing Hub

The number one source for playing and teaching books, guides, CDs, calendars and back issues of the magazine.

In The Best of Technique you’ll discover the top playing tips of the world’s leading string players and teachers. It’s packed full of exercises for students, plus examples from the standard repertoire to show you how to integrate the technique into your playing.

The Strad’s Masterclass series brings together the finest string players with some of the greatest string works ever written. Always one of our most popular sections, Masterclass has been an invaluable aid to aspiring soloists, chamber musicians and string teachers since the 1990s.

American collector David L. Fulton amassed one of the 20th century’s finest collections of stringed instruments. This year’s calendar pays tribute to some of these priceless treasures, including Yehudi Menuhin’s celebrated ‘Lord Wilton’ Guarneri, the Carlo Bergonzi once played by Fritz Kreisler, and four instruments by Antonio Stradivari.

No comments yet