Conductor Peter Manning presents the history and analysis of Robert Schumann’s Cello Concerto, composed in only two weeks and never performed publicly in the composer’s lifetime

Schumann’s Cello Concerto, which is more properly known as his Konzertstück für Violoncello mit Begleitung des Orchesters, allowed for a different type of concerto to develop for the instrument and accompanying orchestra than had been known previously.

When Robert Schumann died in July 1856, his Cello Concerto - written in 1850 over two weeks - had lain unperformed publicly. The concerto had, however, been rehearsed by the principal cellist of Schumann’s Düsseldorf orchestra, Christian Reimers, and subsequently with the composer and cellist Robert Bockmühl, who rather unfortunately found reservations with the general nature of Schumann’s technical and musical-harmonic requirements and indeed his tempo markings especially in the first movement.

After the concerto’s publication in 1854, Schumann continued to correct proofs up until his death and this concerto was indeed the last piece of music he was to work on.

The first performances of the concerto, both with an orchestra and with Schumann’s piano reduction, took place in April and June of 1860. Somewhat like a wondrous ‘sleeping-beauty’, the concerto was awaked in London by the great cellist Piatti in 1866. The piece then found its way to Russia in 1867, and went on to have performances in Paris in 1875 and 1877, Frankfurt in 1870, and Leipzig in 1884 and 1888.

The growing prominence of the piece was increased by cellist Robert Hausmann, starting with performances in London in 1883, Manchester in 1886, and followed by performances by him in Berlin, Hamburg, Köln, Aachen Krefeld, Mannheim, Frankfurt, Braunsweig, Bonn, Menningen, Kassel, Hannover and finally Leipzig again in 1892. There is strong evidence that Hausmann’s last performance of this piece was in Dessau in 1896.

This concerto, like so many before, has relied on the greatest cellists of the day to popularise performances of this masterpiece and its unique form, which freed the compositional requirements of the Baroque-Classical concerto to one of a free-flowing and highly original musical dialogue between soloist and orchestra. Clara Schumann writes about the elements of his new style as a ’Romantic quality, the vivacity, the freshness and humour, also the highly interesting interweaving of violoncello and orchestra are indeed wholly ravishing, and what euphony and deep feeling one finds in all the melodic passages!’

Read: Baroque cello playing: Going for baroque

Read: Cellist Paul Katz on creating your ideal sound with vibrato

The work very much owes today’s prominence to the championship of cellist Pablo Casals in the 1920s, who, after 1896, was the next musician to re-awaken the piece. It was a time of general re-birth after the horrors of World War One and in some way, the era curiously echoed the concerto’s genesis, which happened in the aftermath of the turmoil and general stagnation of the 1848/49 revolutions in Europe. Schumann responded with his musical language to Erfahrung (the accumulated wisdom passed down from one generation to the next) and the more modern concept of Erlebnisse (momentary experiences of ephemeral disturbance).

Casals, of course, had a major worldwide career and chose the concerto as one of his enduring repertoire choices. This clearly allowed other great cellists of the day to follow on and perform this piece - most notably Gregor Piatigorsky who gave the San Francisco and Washington premieres in 1947 and 1956 respectively, some one hundred years after Schumann’s death.

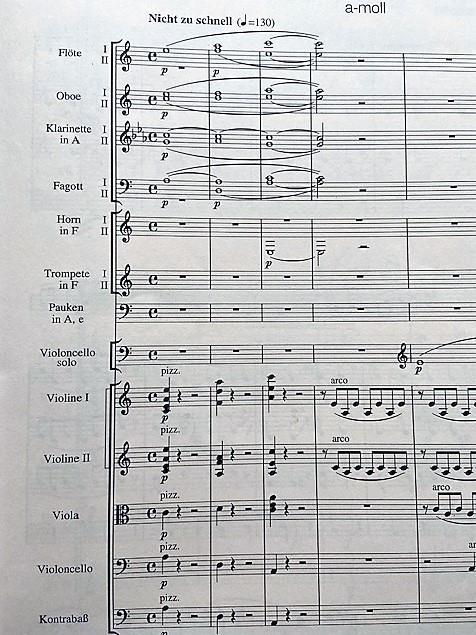

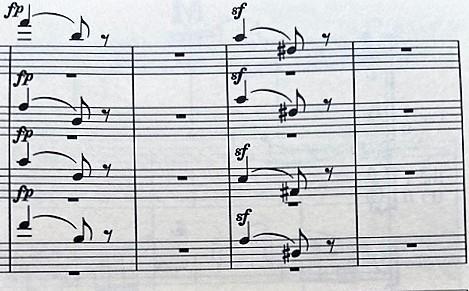

The concerto’s success in today’s world stems from its emotional and mood shifting compass (Figure 1: nicht zu schnell), which ranges from profound intimacy to sounds of joyous vivacity and tonal, rhythmic and thematic unification. This includes his highly original tonal ciphers, most especially around the name of Clara (the great composer, pianist, and wife of Robert Schumann (Figure 2 of the last movement).

Clara herself also mentions that the concerto is ’written in a way which is most befitting to the cello character’. That is to say that the lyrical nature of the instrument could be framed around the greater potential of virtuosity, and also in no small part at that time helped by the emergence of the cello ‘end-pin’, which came into prominent usage in the 1850’s and gave greater physical freedom of expression and technical ease for cellists.

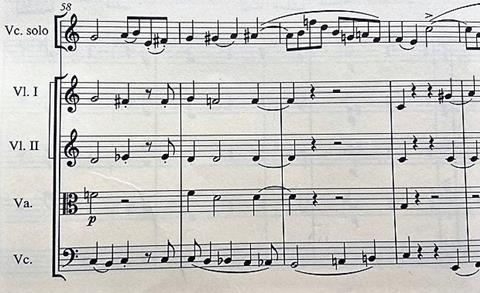

The orchestral writing flows between the commentary of the solo line and in turn develops the dialogue and emotion between itself and the available ‘colour’ of instrumentation, particularly as a result of a shared leading musical line connection (see Figure 3 example of bar 58 in the opening movement) between soloist and orchestra. This is a deviation from the more usual early Baroque-Classical manner of orchestral accompaniment in the concerto form.

At the heart of the piece is a slow movement marked Langsam, in which we are introduced to a second solo cello from within the orchestra (notably Brahms used this device in his second piano concerto). This compelling choice gives a most pronounced and intense intimacy of music dialogue. We might remember that the last notable cello concerto was written by Haydn in 1765 and that the cello repertoire was then comparatively small, made up of works by the composers Boccherini, CPE Bach, Vivaldi, Stamitz, Breval, Duport and John Garth.

Watch: Steven Isserlis performs Haydn Cello Concerto in D

Read: Joy, warmth and humour: Natalie Clein on Haydn Cello Concerto in D major

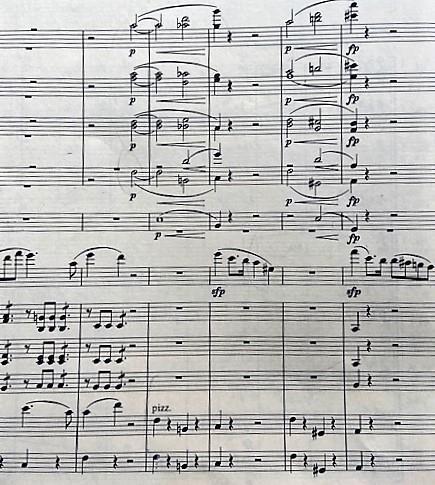

On a key-structural note, the concerto is centred around the A major/A minor tension and release concept, which creates a greater tenderness and tonal differentiation than that of the more usual cello concertos written to that date in the keys of D major and C major. Elsewhere, the orchestra and soloist have leading lines forever flowing and exchanging dialogue (see Figure 4 of the second movement) with length of musical phrase, intensity, speed and phrase shape. All of these devices are employed to create a fuller dialogue than had been the case in earlier cello concertos. The piece has a most unusual accompanied cadenza in its last movement, and it is only after 20 minutes of musical conversation and argument alongside chamber music like textures and motto structures that Schumann brings us home again in a blaze of traditional concerto last movement optimism.

On a closing note, it is fascinating to hear the concerto as a continuous movement, thereby allowing no applause to take place between movements (which Schumann disliked), as this device allows a great sense of the uninterrupted tryptich and provides an entirely modern narrative.

PETER MANNING

ARTISTIC DIRECTOR & PRINCIPAL CONDUCTOR , BATH FESTIVAL ORCHESTRA

The Bath Festival Orchestra and conductor Peter Manning will be joined by Dutch cellist Ella van Poucke to perform Schumann’s romantic Cello Concerto in A minor, Op. 129, at their upcoming Kings Place concert at 7.30pm on Wednesday 9 March.

No comments yet