For the Armenian cellist, Tchaikovsky’s Rococo Variations allows for incredible freedom of expression – and even has the ability to heal

Tchaikovsky’s Variations on a Rococo Theme has been with me almost since I started learning the cello. I was around six or seven when my father came home with a videotape of Yo-Yo Ma playing the piece with the Leningrad Philharmonic under Yuri Temirkanov. It was the first time I’d ever watched a performance like that – it was a special gala concert for the 150th anniversary of Tchaikovsky’s birth, with Itzhak Perlman and Jessye Norman also in attendance – but I’d never seen anything like Ma’s playing before. Even though I was so young, I could sense his freedom of expression, creativity and the way he responded to Temirkanov; it was shocking and impressive in equal measure and I knew then that playing the cello in this expressive way was how I wanted to spend the rest of my life.

I like to think that my own interpretation is fairly free and imaginative, too. As with all themes and variations, it’s a diverse piece and allows for a lot of creativity from the player. It’s also quite divisive, in that cellists either tend to see it as a predominantly Russian work, while others view it as ‘rococo’, in its elegance and joyfulness. The way I see it, Tchaikovsky’s achievement was unique in that he managed to combine his mastery of the rococo style with a distinctly Russian soul. The second and fourth variations I see as quintessentially rococo, while the third and sixth could be nothing if not Russian!

There are so many different interpretations of this piece, I think it’s essential to go back to the score and see exactly what the composer wanted, the words he used and the tempo markings. This has to be at the core of any performance, and only after you’ve absorbed it can you bring in your own ideas. It’s a hard thing to do, given the popularity of the Rococo Variations; it would be almost impossible to avoid all the available performances on YouTube, but with any new piece I always try to find my own interpretation before listening to someone else, if I feel I need to.

Read: Sentimental Work: Ray Chen

Read: Sentimental Work: Amanda Forsyth

Read: Sentimental Work: Anssi Karttunen

When I was preparing for the final round of the 2011 International Tchaikovsky Competition, I remember thinking about this dilemma. I had two choices: either give a very traditional ‘by the book’ performance, which the jury members might be expecting and would probably mark more generously; or play the way I wanted to, which would make me feel more comfortable on stage. It was a very difficult decision for me to make: obviously I wanted to give myself the best fighting chance of winning, but in the end I stayed true to my own interpretation and reasoned that the jury might like to hear something new.

I can still remember shaking backstage before my time came to go on – but not through fear. That morning I had come down with a terrible fever, and my temperature was almost 40C. Right up until I had to go on stage, I didn’t know if I could make it through the 20-minute piece. But when I sat down and started playing, it was as if the fever just floated away. I felt perfectly healthy and played just the way I wanted to.When I came offstage, the fever returned but was much less severe than when I went on. This is how I know that music really does have the power to heal; and nowadays, when I feel as if I’m coming down with something, rather than go and lie down, I’ll pick up the cello and start playing. It always improves me, mentally and physically. And, as it turned out, the jury were none the wiser and awarded me first prize, proving I was right to play the way I wanted.

-

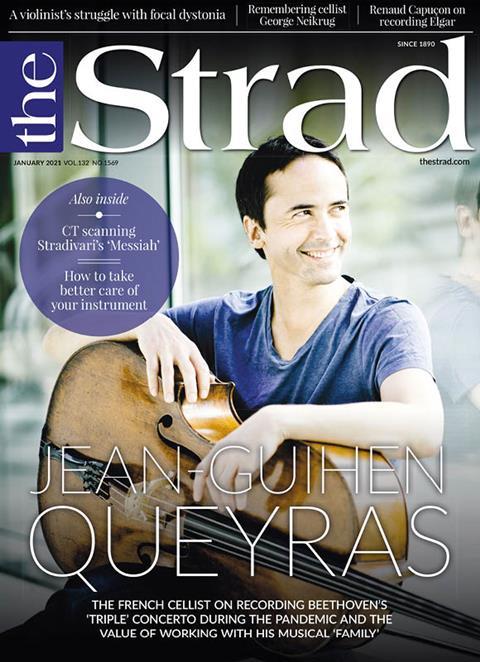

This article was published in the January 2021 Jean-Guihen Queyras issue

The French cellist on recording Beethoven’s ‘Triple’ Concerto during the pandemic and the value of working with his musical ‘family’. Explore all the articles in this issue. Explore all the articles in this issue

More from this issue…

- French cellist Jean-Guihen Queyras

- CT scanning Stradivari’s ‘Messiah’

- Remembering cello tutor George Neikrug

- Renaud Capuçon on recording Elgar’s Violin Concerto

- How players can take better care of their instrument

- Playing Tchaikovsky with just two left-hand fingers

Read more playing content here

No comments yet