Cellist and online editor Davina Shum examines the parallels between rock climbing and music-making and how an approach in one discipline can inform the other

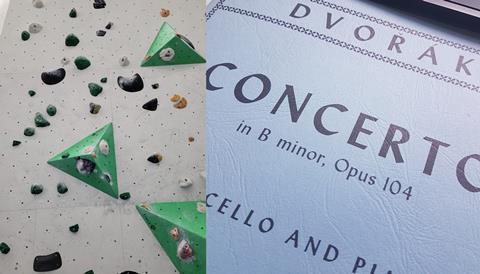

As a player and a teacher, I’ve always found it useful to use analogies from the non-musical world to relate to particular aspects of string playing. One of my favourite pastimes is bouldering, which, if you don’t know, is a form of rock climbing. Climbers scale walls up to 4.5m high following a route of colour-coded holds, known as ‘problems’. Problems vary hugely in difficulty, depending on the type of holds used (easy and grabbable ‘jugs’, to finger-tippy ‘crimps’), the angle of the wall (ranging from a forward-leaning ‘slab’ to gravity-defying overhangs) as well as the route dictated by the holds. While it’s a huge workout for your entire body (hello, core muscles that have been dormant over lockdown), it’s also a workout for your mind, as you must actively solve problems to ensure you get to the top of the wall successfully following the route, preferably without falling off and injuring yourself. You’re also not attached to a lead or harness, which makes it rather thrilling.

Bouldering requires intense focus and precision, yet is often described as creative. No two people are going to have exactly the same approach (or ‘beta’ in climbing terms) for one bouldering problem. Everyone has different strengths and weaknesses, and bouldering is a prime example of learning how to play to your strengths. You might muscle your way up to get to the top. Maybe you prefer to ‘dyno’ (move dynamically, involving swift leaps and swings) to your next hold. Or perhaps you have the hip flexibility to reach that foothold that’s just a bit too high for everyone else. It’s up to you to find a solution that suits. But not without first ‘reading the rock’. Holds are all different – depending on the shape or size, they could suggest that you start sitting, approach from a particular side, use your fingertips rather than your palm – and involve many different techniques. It’s the challenge of the climber to recognise what technique is required in any given scenario.

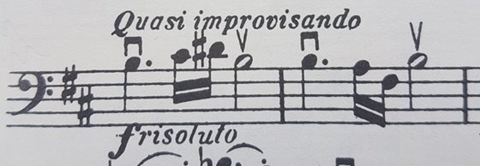

Therefore, I find this approach to problem solving invaluable in my own playing and teaching. You may encounter a technical passage in a piece and think, ‘How on earth am I going scale this?’ the same way you’d look at a climbing problem and think ‘How on earth am I going to scale this?’ Like how climbers must ‘read the rock’, players must learn to approach passages to figure out what is required of them musically and technically. Possibly the simplest examples would be in terms of dynamics, articulation and character: If I were to play the opening passage of Dvořák’s Cello Concerto, which is marked forte risoluto, I probably wouldn’t start this quietly in the middle of my bow, flautando. But that’s just me…

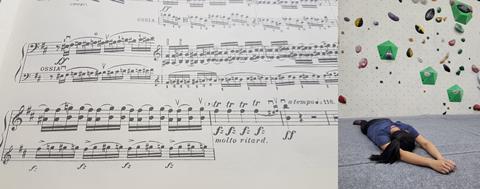

Learning to identify issues and what steps are needed to overcome them are skills necessary to both climbing and music-making – particularly in the area of sightreading. Go to any climbing wall and you’ll no doubt see climbers assessing their chosen problem, often miming what they think they’ll need to do. It’s certainly helpful to anticipate difficult points in a climbing route, rather than flailing about mid-route wasting energy and eventually disrupting the flow with which you execute your problem. Same goes for music. How many times have we heard from teachers to ‘read ahead’ when sightreading? And sometimes, things don’t go to plan – but it’s how we pick ourselves up, assess the damage and have another go that defines our success.

I often find myself thinking about the documentary ‘Free Solo’ which charts climber Alex Honnold’s journey to scale El Capitan with no ropes – a feat that took the lives of several climbers in years before. Honnold memorised every crack, every surface, every incline of his chosen path up the 2900ft climb, a mammoth feat that was fuelled by his thorough preparation of visualisation (not to mention years of physical training). While musicians are good at practising the physical aspects of playing, this highlights the importance of knowing our musical intention, how we must link our practice with having a clear idea of what we want to communicate – after all, that is the point of making music!

And if that seems difficult, just remember at least it’s highly unlikely you’ll fall to your death while practising your concertos.

Read: Popper studies: celebrating the small victories

Read: Opinion: Relaxed body, focused mind

Read: Paganini’s 24 Caprices: achieving a musically informed performance

No comments yet