No one said that living in a quartet was easy - but the most successful groups develop a unique identity that survives vitriolic relationships and even personnel changes, writes Paul Robertson. From 2005

It is remarkable that despite radical reforms and changes of personnel, string quartets can retain a unique identity or persona. In the Medici Quartet, of which I was a founder member and leader for nearly 35 years, we had two key changes: our original violist after ten years, and the second violinist ten years later. On both traumatic occasions, I vividly remember having the sense that the group was nonetheless still very much alive. It felt inevitable that someone would step into the breach and replace the absent voice.

Quartet connoisseur and regular Strad contributor Tully Potter articulates this well when he describes how after about ten years, quartets evoke a kind of virtual fifth member, a personification of that part of an ensemble greater than the sum of its parts.

Towards the end of the Medici's first decade, I remember becoming increasingly aware of this ghostly figure in our concerts - although I hasten to add I never actually saw him.

Perhaps this disembodied identity represents all the years dedicated to creating a common emotional musical language through endless, repetitive practice of expressive gestures: four conscious musical bodies seeking to bring to life a fifth - the quartet. It must also be a clue as to how a quartet's interpretation can remain consistent in spite of a change in personnel.

Concert pianist and research scientist Manfred Clynes spent years analysing how emotional gestures become the underlying material of musical interpretation. As part of his work he measured an established string quartet's performance timings of a late Beethoven quartet.

He discovered that no matter what musical re-workings the group made to their interpretation, their actual performance was virtually unaltered in its overall timing.

I observed the same thing when making a programme recently for BBC Radio 4, The Dynamics of Music. As part of a sequence exploring personnel changes across our career, the Medicis were taped rehearsing the slow movement of Beethoven's op.132 Quartet. The producer cross-cut this with our Nimbus recording made 15 years before, when our original second fiddle was still playing. The intention was to illustrate how we had changed. But in fact, putting aside inevitable acoustical factors, there was absolutely no difference! Tempo, phrasing, sonority and emotional intensity were indistinguishable despite a different player and instruments.

Read: A string quartet is an ‘instrument’ that students must master

Read: 10 tips for achieving long-term success with your quartet

This is thought-provoking and quite disturbing. After all, if nothing changed across so many years, whatever happened during all those thousands of rehearsal hours? With such a powerful group personality, does it even matter who is actually playing?

To comprehend the enduring identity of a quartet, we need to understand the personalities within it. There are many ways of trying to calculate the balance of power and influence of individuals in an ensemble. Like all organisations, quartets try to sustain consistency in many different ways. Some even establish 'democratic' voting systems to create some kind of equity of influence. Others use seniority as the power broker - the longer you've survived, the more significant your contribution to decision making.

The musical world is full of funny and painful anecdotes of vitriolic and vicious breakdowns within quartet relationships: second violinists caught in Oedipal tensions with the dominant leaders they impotently long to usurp; musical Iagos, jealously machinating against their musical fellows; and so on. There must be some truth in the music profession's ungenerous description of a string quartet as one good violinist, one bad violinist, one failed violinist and one person who hates all violinists.

In founding a quartet I hoped to create a family full of affection, an ideal group of siblings. As an only child I knew nothing about the other side of sibling relationships: the jealousies and resentments, competitiveness and possessively destructive loves and hates.

PERSONALITY TYPES

There are many approaches to understanding personality types but the one that pleases me, partly because it is based on four fundamental characters, is the most ancient. Its creator, Hippocrates, describes people as being choleric, phlegmatic, sanguine or melancholic. Successful teams have all these qualities represented.

Cholerics are always leading and directing. They are never in doubt, because, after all, it's natural to lead if you always know better than everyone else. Perfect foils to domineering choleric natures, peaceable phlegmatics are delightful - always seeking to negotiate and make everyone happy. They may tend towards indecision at times. Cholerics need phlegmatics and vice versa - leaders need followers and followers need leaders.

One strength of melancholics is their perfectionism. They love to make lists, keeping a book to note their mileage, then calculating the fuel efficiency of every trip. They share such exciting discoveries during rehearsals. Not surprisingly, after a performance it is the melancholic who fastidiously informs everyone just where they rushed or had the wrong bowing. Wonderful disciplinarians, they may become easily discouraged and they never forget a slight. It's not hard to see how easily bossy cholerics can mortally offend sensitive melancholics, who may silently harbour grievances over years.

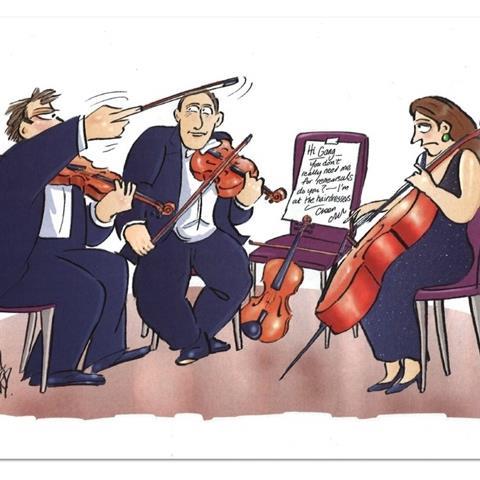

Sanguines are charming, bubbly and full of fun. Irrepressible, they sometimes have the attention span of a gnat and chat continually. Sit down to rehearse a Beethoven quartet and after an initial play-through, just as everyone else is gathering up their energies for some serious rehearsal, sanguines will be out of the door telling everyone excitably that they are late for the hairdresser, shoe shop or party. 'Anyway,' they will say exasperatingly as they wave goodbye, 'you've all played it before, haven't you? So what's to rehearse?' They may perform superbly, but without any sense of what has been agreed in rehearsal. For cholerics like myself, sanguines seem unbearably facile yet uncannily brilliant.

This is the basic alchemy of the personalities that a successful group must sustain. No wonder few ensembles endure the travails of a long career. That elusive fifth figure, 'quartet', only begins to manifest when a sufficient yielding or melding of individuals' predominant temperaments has begun.

For us, Beethoven was the ultimate hair shirt, the place where we were continually obliged to face our habitual responses and forge something new That's why most quartets never get to play Beethoven really well and for those that do, all sorts of strange metamorphoses occur. Perhaps that's also why the results can be so unfathomable to many listeners. Players grow change, adapt,' die' and reform, like cells in the body, while the collective identity remains - at least for a span.

So how do these intertwined personalities go about finding a replacement? The choleric expects someone to rush to serve, and awaits that someone to elect themselves. The melancholic makes a list of the qualities needed from his list of potential candidates, noting ideal audition pieces. A sanguine tells everyone just what they need to do and what fun it's all going to be, but hasn't got enough time to attend the auditions because of some vital prior commitment. Equitable phlegmatic, meanwhile, tries his best to find a compromise with which everyone might be content. Additionally, the sibling rivalries that underlie the original fracture are in powerful play.

So, as with every decision making aspect of this musical micro-democracy, defining and discovering the perfect new player is an extraordinary and exasperating mixture of the seemingly rational and the frankly bizarre, in which stated values are often at total variance with the actuality. Perhaps this is inevitable: after all, the relationship in truth has more of the quality of a marriage than a business partnership about it, and how many of us really understand how we set about falling in love?

While searching, everyone's rhetoric may be full of admirable sentiments: 'Well, we need someone experienced, talented, responsive, committed, malleable...' and so on, but when it comes to it, even the most admirable candidate can be neglected in favour of somebody who is simply and indefinably 'just right' in personality.

That person is somehow refreshingly new yet still able to let established members feel themselves psychologically 'intact'. Does this imply weakness? Not necessarily. In fact when playing and talking with a potential candidate, a mass of largely unconscious emotional messages is being processed, much like the act of music making itself but curiously accelerated and acute, every phrase and gesture weighed, measured and assessed. Subtle, certainly. Rational - certainly not!

Did you think living in a quartet was easy? Think again. At its simplest it's a double marriage and the divorces are commensurately complex. Thank God for the noble harmony of the music! But if we seek all the answers in the masterpieces of the repertory, bear in mind that Beethoven, master of the quartet though he was, never made a family. Fortunately his genius can lift us as it did him, to a place far beyond human frailties.

This article was first published in The Strad's July 2005 issue

Masterclass: Beethoven String Quartet op.132

Jacqueline Thomas, cellist of the Brodsky Quartet, which celebrates its 50th anniversary this year, looks at a third movement written by a composer convalescing from a near life-ending illness

- 1

Currently

reading

Currently

reading

The harmonious string quartet - a balance of four personality types

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

No comments yet