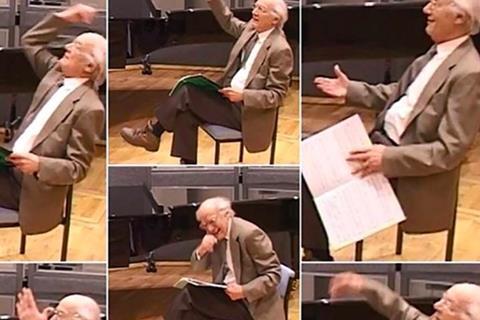

One of the 20th century’s greatest violin pedagogues, Béla Katona would have turned 100 this month. Here Tully Potter speaks to former pupils – mainly at London’s Trinity College of Music – about the success of his teaching methods

The following is an extract from a longer article in our April 2020 issue. To read in full, click here to subscribe and login. The April 2020 digital magazine and print edition are on sale now.

Pupils stress Katona’s work ethic. Nic Fallowfield is typical: ‘He was larger than life and boundlessly generous: if it took three hours for you to “get” what it was he thought you needed to take from your lesson on any particular day then your lesson would last three hours, and two other students would be waiting for their lesson, in the room, by the time you finished. His commitment to his students was absolute, total. He was a masterful and demanding teacher, hard but never unfair, never unkind. His energy was prodigious. He was both methodical and completely inspirational.’

Catherine Thomas, who had been with him for two years before going to Trinity, says: ‘Katona stipulated that his handful of students did eight hours’ practice a day.’ His sense of humour could be robust: ‘My laziness led him once to threaten to throw me out of the third-floor classroom window where he taught! I would start my lessons with fortissimo open strings and then the studies took up a great deal of the rest of the lesson. It was when you had a piece ready that his incredible teaching was apparent. He would shout, sing and even jump. The music stand was occasionally put on top of the grand piano, so as to get the upright violin posture. He insisted on musical, passionate performance and I was very lucky to have learnt with him, as he was inspirational; and while I have a more smiley approach in my own teaching, I am really fussy about tone and violin hold.’

- Read: Béla Katona: A Teacher Through and Through

- Read: Béla Katona: A Pupil’s Perspective

- Read: Obituary: Béla Katona

Violist Norbert Blume recalls a blistering regime: ‘Béla Katona was a remarkable man. Possessing endless energy, patience and devotion, he was a truly gifted teacher who would bring out the best in you. He also demanded tremendous input from his pupils. Katona would then praise, encourage and help you through low points in your work. He never tired of listening to the entire Flesch scale system, played to him in a different key each lesson, and also Gaviniès, Dont and Paganini. Developing a good technique was a natural, almost wholesome process, to become an integral part of your whole being, not an analytically acquired appendix. I remember working on a slow movement of a Mozart concerto for weeks, maybe months, until one day I got an inkling of what Katona meant by “letting it happen”, in both a technical and a musical sense. I am forever grateful for his guidance and for opening the doors to a deeper understanding of music.’

This is an extract from a longer article in our April 2020 issue, in which Tully Potter charts Béla Katona’s life and career and speaks to his former pupils about the success of his teaching methods. To read in full, click here to subscribe and login. The April 2020 digital magazine and print edition are on sale now.

No comments yet