Varnish maker Joe Robson explores the mystery of the special deep red varnish colour that makes Antonio Stradivari’s later instruments so attractive

The following is an extract of a longer article in The Strad’s September 2018 issue. Click here to subscribe and login. Alternatively, download the magazine now on desktop computer or via the The Strad App, or buy the print edition

We live with the myth and lore of the beautiful finishes of the classic Cremonese instruments – but what we now call ‘the Stradivari varnish’ has come to stand above everything else. Although it is similar to the finishes of his predecessors and contemporaries, in particular those of the Amati and Brescian traditions, from the 1680s onwards something singular identified Stradivari’s work.

Human beings see the colour red and its variations better than any other mammal. The significance of red in our lives goes back to the Neanderthals, who buried their dead in red ochre. Every human culture has assigned some version of power to this colour. In ancient China it was the colour of health and prosperity. In the Arab world it signified divine favour and vitality. The Roman Empire was ruled by a class whose name, coccinati, literally meant ‘those who wear red’. It is the colour of kings and queens, cardinals and demons.

Stradivari was making instruments for the wealthy and powerful that were literally the colour of money

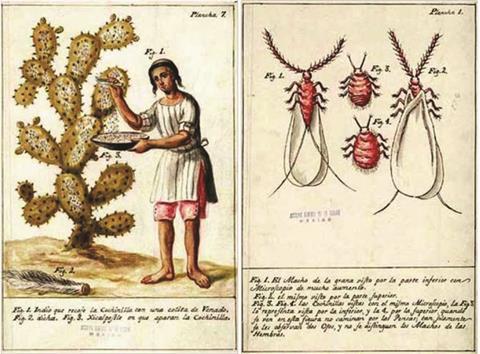

When Hernán Cortés began the conquest and plunder of the Aztec Empire in c.1518 he easily identified kings and royalty by their appearance, since they were dressed in cloth and feathers dyed in the finest reds and purples a European had ever seen. Cortés sought and found the gold he promised the Spanish court. However, as the news of this magnificent red reached Spain, a new explosion of wealth and power there was fuelled by a tiny insect: the cochineal bug. A group of Spanish families formed a cartel that controlled the trade and fed the eruption of demand for dyes made from cochineal. This funded the reign of King Philip II and the creation of the Spanish Armada. It also served to underline the hatred and competition between Spain and England, as Philip had been consort to the vilified Mary Tudor.

The varnish on Stradivari’s earliest instruments closely resembles that of his mentor, Nicolò Amati. But by the mid-1680s his varnish had become strikingly more red, and was acquiring those traits that would set his work over and above that of his considerably talented contemporaries. Cochineal varnish became the signature appearance for instruments made in the Stradivari workshop. Stradivari was making instruments for the wealthy and powerful that were literally the colour of money – and he was the only maker to have this incredible varnish.

This is an extract of a longer article in The Strad’s September 2018 issue. Click here to subscribe and login. Alternatively, download the magazine now on desktop computer or via the The Strad App, or buy the print edition

Reference

No comments yet