Fifty years ago, David Oistrakh premiered Shostakovich’s violin sonata. Here Andrew Morris discusses the work with Julia Fischer and Vadim Gluzman

This is an extract from a longer article in the May 2019 issue of The Strad, in which Julia Fischer, Vadim Gluzman and Gidon Kremer contribute to a discussion of all three of Shostakovich’s works for violin soloist – the Sonata and two Violin Concertos. To read in full, download here. To order the print edition, click here.

The Violin Sonata, composed in 1968 for Oistrakh’s 60th birthday, was no genial marker of the passing of the years; Shostakovich could scarcely have written a more demanding instrumental work. The first of the three movements begins with a twelve-note row, a modernist device with which he toyed in the 1960s. An unremittingly harsh Allegretto precedes a variation finale built on a passacaglia, rising at its centre to an exchange of musical violence more fearsome than almost anything else he wrote.

After performing the sonata to an invited audience at a session of the Union of Soviet Composers on 8 January 1969, Oistrakh expressed (here in a translation by Bryan Rowell for the DSCH Journal) his delight with the new work: ‘I’m much, much happier than anyone in this room in the sense that I’ve known this sonata longer than all of you […] I’m deeply moved by every single modulation, every single harmony, every single melody.’

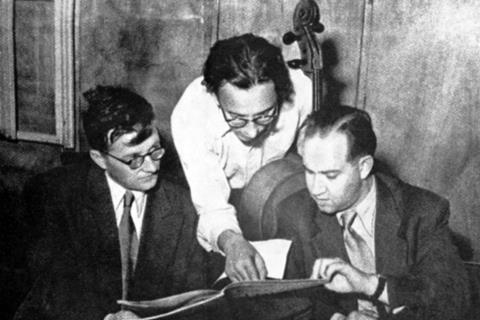

- The sonata’s reputation was made by this recording of the official premiere in Moscow on 3 May 1969, given by Oistrakh and Sviatoslav Richter: ‘The recording with Richter is incomparable in its gravitas and the belief in what is happening,’ says Vadim Gluzman.

Julia Fischer has recently included the sonata in recital programmes. ‘There is no bar where you can just play, or enjoy,’ says Fischer of the sonata’s special challenges. ‘You always have to have complete concentration, and that’s what makes Shostakovich so hard. It’s not that there are passages that you practise for two months until they finally work. Once you’re not concentrating, you lose the entire piece. It just goes, like water.’

The ferocious second movement is also a substantial physical challenge, right at the centre of the piece. ‘Potentially it can be played with sheer physical power, and one can survive for quite a long time if one keeps that under tight control,’ says Vadim Gluzman. ‘But if you dive into it head first, there is no chance of having anything left for the last movement. I remember the first time that I played this piece, I went all in, and at the end of the second movement I thought, “I can’t go on! I have nothing left.” Then my string broke – at the very beginning of the third movement. I was so grateful!’

The exhausted finality of the Violin Sonata’s closing pages foreshadowed much of what Shostakovich went on to write in the remaining seven years of his life. ‘He reaches a point where even music is not enough, and yet he pushes further,’ says Gluzman of Shostakovich’s late works. Declining health and the knowledge of the traumatic century through which he had lived haunted his last years and their music.

Shortly after the first performance of the Violin Sonata, the composer told the audience at the unofficial premiere of his 14th Symphony: ‘It will be a long time before our scientists figure out immortality, and death awaits us all. I see nothing good about such an end to our lives.’

Fifty years after the first performance of his last work for violin and piano, Shostakovich’s music still jolts audiences to attention. ‘I think that when I put Shostakovich on the programme, I don’t want people to feel amused,’ says Fischer. ‘I don’t want them to go to the concert and just have a happy time. I want them to rethink how they live and if there’s anything that they can provide to fight injustice, poverty and pain, and to take a good look at the world as it is at the moment.’

This is an extract from a longer in the May 2019 issue of The Strad, in which Julia Fischer, Vadim Gluzman and Gidon Kremer contribute to a discussion of all three of Shostakovich’s works for violin soloist – the Sonata and two Violin Concertos. To read in full, download here. To order the print edition, click here.

No comments yet