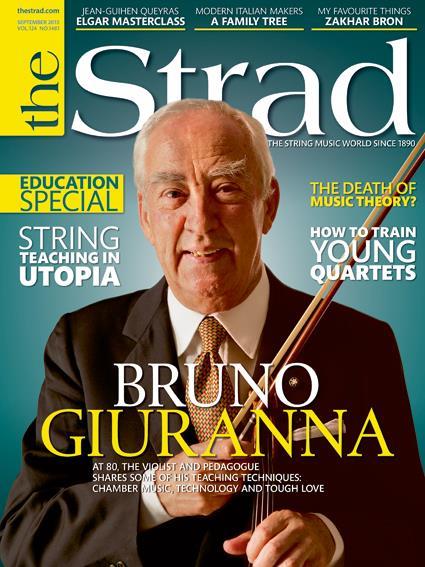

The viola player and teacher offers his advice on mastering the instrument

More quotes from the great violist and pedagogue Bruno Giuranna, concerning his approach to teaching and the different schools of string playing:

Storytelling

There are some pieces of music for which you should have the attitude of telling a story to a child. If you use the same voice for a child as talking about the weather, the child will not listen to you. With a soft voice and a mysterious attitude you will somehow capture the child’s attention talking. Is this passion happening now, or are you telling someone about this? There are tunes that it’s better to play as if you’re remembering something. All of this is normal for an actor. We have to search for an interpretation for what we do.

With students who find this difficult I ask them to play a phrase. Then I ask them to play it different ways – melancholic, nasty, energetic, martial. It’s amazing how they are able to do that. Then I say, ‘Never play anything without deciding what it’s going to be.’ That works very well.

Rhythm

Rhythm is the opposite of passivity. I show students how not to play with a passive rhythm. A metronome is a tool that can be used well, if we’re intelligent when we use them. We can establish a tempo for something we have to play – Kreutzer no.1, for example: tock–tock–tock. Stop the metronome, play, and check the tempo you’re playing at the end. Metronomes can also be used in music: at which tempo do I want to play this tune? Decide with a metronome, write it down and leave it for a day. The next day you can take the metronome and you’ll probably go, ‘Oh, it’s that slow,’ and continue. In this way, you fine-tune your feeling of the tempo.

Normally people don’t think about tempo and it’s ‘as it comes’. If you want to construct the unity of a movement of a Classical sonata, there are going to be differences, and in general the second theme is going to be a more relaxed than the first theme, for instance, but there should be a unity. This research is important, because we tend just to play ‘as it comes’, and this ‘as it comes’ is the enemy of a real performance. It means there’s a crescendo, and there’s also an accelerando, and a diminuendo and a ritardando. Music should be what we want and not what happens.

Chamber music

If I see that two performers split in a performance I say to one, ‘You are the boss, you change tempo,’ and the other one has to follow. Then I swap, and the other is the boss. It works very well. When we play, our concentration goes into what we’re doing and if we keep that then we don’t listen. So we have to detach ourselves from what we are doing and keep 20 to 30 per cent open for listening. It’s a psychological thing that has to be done and it can be learnt quickly. If a player isn’t following the piano when it has a faster motion, I ask the pianist to change, I even tap a faster tempo. The first rule of chamber music is to be together. Let’s be wrong, but all together.

Schools of string playing

The different schools have somehow been mixed together. When I was young, there was the French bowing school and the Russian one. Then I saw Kogan playing and I felt he was playing with the French school so I had the feeling that schools didn’t exist any more. Schools tell you, ‘This is what you should do’; the modern way is, ‘Let’s try what is the best in order to obtain this.’ It’s more a search to see what’s better. There are many theories and very often these theories start from the player, but they should start from what the bow actually wants to do. The bow wants to go up and down. What’s the best way to obtain this?

Viola sound

I often ask my students to play in a piano dynamic for a month. Often their forte is not forte because there are useless tensions. I ask, ‘Play this phrase piano and now play it forte. What do you do?’ They say, ‘I press, I use more bow.’ Nobody tells me they play closer to the bridge. It’s not about pressing more. For people who have the habit of trying too hard with the bow, I get them to practise for one month at a maximum of mezzo piano in order to find the fluid movement. Then we see how they can make forte without changing their effort. We try a different point of contact, a different speed, using more bow: we don’t just brutally use more strength.

Interview by Ariane Todes

Click here to return to Part One

Download the September issue to read the full Bruno Giuranna interview.

No comments yet