There’s a wealth of variety when it comes to the studies string teachers can use with their students. Vicky Hancock asks some leading pedagogues which ones they find most useful

This article is taken from the September 2012 issue of The Strad

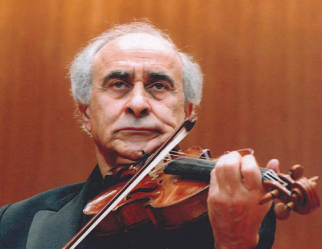

FELIX ANDRIEVSKY violin

TEACHES AT Royal College of Music, UK

STUDY Caprice no.2 in B minor from 24 Caprices for Solo Violin by Paganini

I believe that studies give students the explanation behind a technique – the basic principles. But the technique itself is not developed until they are playing musical works. For a player to learn technique, the basic elements need to be played in a variety of combinations, not just in a single way – a bow stroke like spiccato, for instance, can be played loud, soft, fast, slow; diminuendo, crescendo, accelerando and more.

But of course, we do need the building blocks and there are great albums of studies, such as those by Kreutzer, Dont and Wieniawski but for me, Paganini is the best. Although he composed his caprices as studies, they are incredibly musical. They include beautiful melodies that imitate wind instruments, groups of stringed instruments or different emotions and cover every possible technique and and every imaginable variation.

The greatest caprice is no.2. It’s the best medicine conceivable for string-crossing, spiccato and the right arm. Paganini wrote ‘dolce’ at the beginning, and despite the difficulties this involves for the player, listeners should feel like they are eating chocolate or honey. Although it is written in semiquavers almost all the way through, the melody follows the quaver. It starts a little bit sadly in B minor, and then becomes happy in D major. It’s a very beautiful line. The tempo is not fast, it’s moderato, and it’s not a question of brilliance or speed. It’s about delicacy.

The spiccato stroke needs to be played between the middle of the bow and the frog, and because of the dolce marking it shouldn’t be too short, but it should have an element of détaché. Holding the bow so low down is difficult, and you need to have control of all the joints in the right hand. All the little tendons in the hand, wrist and arm are involved in moving the bow from left to right. You don’t hit the string – it’s more a case of pushing and pulling.

LEON BOSCH double bass

TEACHES AT Trinity Laban Conservatoire of Music and Dance, UK

STUDY Etude no.1 in C major from 30 Etudes for the String Bass by Simandl

The whole book of studies by Simandl takes a bassist from a basic level to an advanced one. Each etude covers a particular discipline and has a useful application in the musical world. In my view, if a player studies them properly and meaningfully, they should be able to earn a handsome living. Etude no.1 in C major looks terribly basic and simple on the page, yet it covers all the fundamental aspects of playing – you need every single facet to be a bassist and musician.

It’s a great diagnosis tool, and it’s the first thing I give to students and young professionals who come to play to me. By the end of the first few bars you can really see how good someone’s sound production, bow control and distribution, pitch perception and rhythm are. Often, young players are surprised to be asked to play something that looks so easy, but are horrified when they realise what it shows them about their playing. Then they go away and try to learn it properly, which can take months, but once you can play it well it transfers to everything else you do, however complex.

Another thing I especially like about Simandl’s studies is that unlike a lot of other etudes for stringed instruments – which are almost always purely technical affairs – they emphasise the musical aspects of playing, dealing with technique through the music. Each one has a magnificent underlying musical element. No.1 is all about discipline and control and is a bit like the Prelude to Wagner’s Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg.

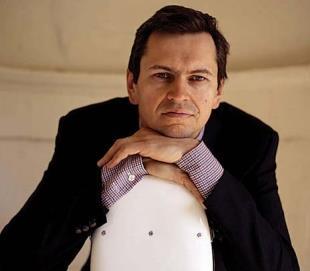

VICTOR DANCHENKO violin

TEACHES AT Peabody Institute of the Johns Hopkins University, US

STUDIES Nos.1 in A minor and 2 in C major from 42 Etudes for Violin by Kreutzer

The Kreutzer Etudes are a violinist’s bible and absolutely crucial to a player’s development. Each one addresses a specific problem or problems, and prepares a player for both repertoire and more difficult studies, such as those by Dont, Wieniawski or Paganini. Although I recommend many from the 42 Etudes, nos.1 and 2 are, for me, absolutely vital.

Etude no.1 is the best tool for developing a good sound, sustained bow strokes and an even vibrato. I recommend that students start practising the study using a metronome set at 60bpm, and get slower and slower until eventually they can play it at 40bpm. They should try to attain good tone, and full control of their bow and vibrato.

An advanced student can start to learn the etude aged around 12 or 13, but all players, of any age – 20, 30 or 60 – should return to this study from time to time, for as long as they play the violin. Etude no.2 addresses lots of different basic bowings, including détaché, martelé, spiccato, staccato and ricochet, in different combinations.

A student should start learning this study as soon as possible, certainly before they are ten years old. When they first learn it, it should be practised consistently and diligently, but as with no.1, they should return to it again and again, for as long as they play the instrument. It will help them polish their skills and feel more comfortable with all the different strokes.

LEONID GOROKHOV cello

TEACHES AT Guildhall School of Music & Drama, UK; Hochschule für Musik, Theater und Medien, Hanover, Germany

STUDIES Etude no.1 from the High School of Cello Playing op.73 by Popper; Etude no.13 from 24 Etudes for Cello, op.38 by Grützmacher

Popper’s book is all about elegance, economy and legato. It helps you find efficiency, continuous movement and versatility. My favourite is the first etude, which covers all the possible stringcrossing combinations – including those that are awkward or extreme. If you follow Popper’s instructions carefully you will learn to use your right arm in a versatile way, using the upper part for the big movements and the wrists for the small. The whole study should be played with a light spiccato stroke and a lot of the crossings are simply impossible if you don’t follow the given directions.

The study is also a great tool for fingerboard navigation. During the string-crossings, the left hand does a lot of shifting, and some of the intervals are very large. To cope with this I aim to get students to play the etude with very still elbows, and help them to find the best position for both arms. If you have to use your elbow to jump around the cello’s fingerboard, the instrument can seem very long, but if you find a good position for the left elbow, where your hand can reach either extremity very quickly, it becomes manageable. I ask all my new college students to play no.1 so I can explain my views on the use of the arms. It can be played before then if the player is comfortable with the upper positions and if their thumb doesn’t collapse in thumb position.

The Grützmacher etude is a favourite because it really sets up the left hand in thumb position. You play two pages in one position and he does not allow you to collapse your thumb or press too hard – you have to keep your hand rounded. The etude also makes the seemingly impossible possible. He asks players, for example, to play a major 3rd between the third and fourth fingers. It seems incredibly awkward, but once you learn how adaptable and flexible your hands are, it’s possible.

MELISSA PHELPS cello

TEACHES AT Royal College of Music, UK

STUDY Etude no.12 from the High School of Cello Playing op.73 by Popper

Picking one study is very difficult. I use them a lot in my teaching, mainly the Popper studies and the Piatti caprices, which, like Paganini’s, can also be used as virtuoso concert pieces. Studies can never replace the emotional subtlety and nuance needed to play the great cello repertoire, or chamber music, but they are, however, very useful as they take one or two technical aspects, focus on them and develop stamina.

I have strong memories of working on Popper no.12 myself as a student with Paul Tortelier. It’s one of the hardest in the book and I give it to my most advanced students to play. No.12 is all about developing the left hand and isn’t especially melodic. It’s quite chordal, for example requiring the student to play the notes of the diminished 7th scale one after another. The study is largely in thumb position and the modulations are especially challenging for intonation. There are lots of large stretches involved and big interval gaps between the fi ngers. It’s also four pages long, so it develops strength.

I also use Feuillard’s Daily Exercises for Cello and Ševčík’s bowing exercises from his 40 Variations op.3, which take students through many basic bowings in a musical setting – they’re also a bit less dry than other Ševčík examples!

PATRICIA POLLETT viola

TEACHES AT University of Queensland, Australia

STUDY No.5 from Ševčík op.2 School of Bowing Technique

I am a fan of Ševčík ’s op.2 School of Bowing Technique because it allows players to concentrate purely on technique, and helps to establish a solid right hand. Our musical ideas are only realised through the sound we produce with the bow, so it seems obvious to me that this should be a priority for practice. Ševčík uses a theme and variations model, where short phrases are repeated to address one concept at a time, isolating specific areas.

Although such focused attention allows a player to produce results quickly, it’s not easy to practise with the high-level concentration required, and patience and discipline are needed. Doing only small amounts of this work, often, is the most efficient way to progress. The key is to practise with complete mindfulness, to incorporate frequent pauses for evaluation, and to know when to stop. Students often think Ševčík will be easy and that they can get away with very little practice to perfect what seems straightforward, but it surprises them how much they struggle to execute these bowings well.

Although I encourage dipping into sections of the complete Ševčík output, I find that concentrating on only a few of them can be comprehensive. Op.2 no.5 is a good example. It’s a great way for a player to practise most of the major bow strokes in a short period of time. I reduce the length of the theme to the last line only, which still uses all four strings, so that it can be done even more quickly. The study begins with basic détaché strokes, and gradually goes through various legato, staccato, portato, spiccato, accents, dotted rhythms, syncopated legato notes, Viotti bowing, jeté, sautillé, repeated down and up bows and even some dynamics.

It is a complete workout for the bow. The first 40 variations of this study are also particularly useful in developing or maintaining a straight bow. Using defined sections of the bow – the upper half with the forearm and the lower half with the upper arm – allows students to isolate and observe the exact movements required. Then, creating a whole bow is a matter of connecting the two and adding little movements in the arm to ensure a straight bow. They also help ensure that sound quality and consistency are the same in all parts of the bow.

Technique: Playing with expression

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

Currently reading

Currently readingPedagogues’ top studies: Etude of choice

- 10

No comments yet