Janet Banks reviews Janet Horvath’s moving biographical tale of her family, the Holocaust and what happened next

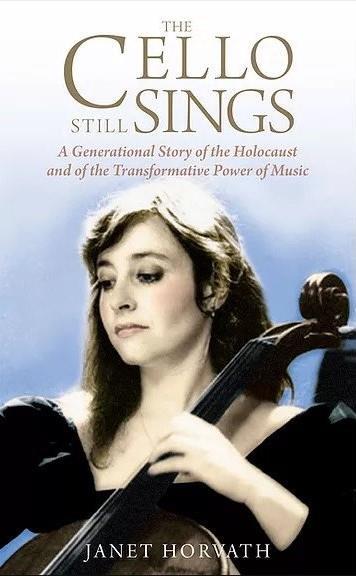

The Cello Still Sings: A Generational Story of the Holocaust and of the Transformative Power of Music

Janet Horvath

393PP ISBN 9789493276802

Amsterdam Publishers $23.95

A chance question en route to a hospital appointment with her 87-year-old father in 2009 led cellist Janet Horvath on a quest to discover her Jewish parents’ Holocaust experiences. She tells their gripping story here with honesty and humour, writing in an engaging style as if talking to a friend.

Brought up in Canada by Hungarian musician parents, she had soon realised that questions about the past were forbidden, and that her Jewishness was something to be kept quiet. Only when she casually asked her father, formerly a cellist in the Budapest and Toronto symphony orchestras, if he’d ever played with Leonard Bernstein, did his veil of silence begin to lift.

‘Yes,’ he said. ‘It was very hot day. He came. To conduct Jewish orchestra in DP [Displaced Persons] camps. In 1948. After war.’ And with that revelation begins Janet’s often harrowing voyage of discovery, via museums, archives, tape recordings and finally her father’s own testimony, written months before he died. It leads her to travel to Hungary and Germany to retrace her parents’ steps and finally, in 2018, to the moment when she is invited to perform Bruch’s Kol nidrei in the very place her father performed with the Ex-Concentration Camp Orchestra 70 years earlier – which is told in the book’s Prologue.

Read: ‘Music was their lifeline’: Excerpt from Janet Horvath’s new Holocaust memoir

Book review: Violins and Hope: From the Holocaust to Symphony Hall

Read: Remembering the Holocaust: Noah Max on ’A Child In Striped Pyjamas’

Kol nidrei, the solemn plea for forgiveness which her father and then Janet had played in the synagogue in Canada every Yom Kippur for 60 years, runs like a musical leitmotif through the book, as does the idea of music’s power to express the unspeakable and to build bridges between people. A generous number of black and white photographs further illuminate the text.

Horvath writes movingly and amusingly of growing up as a child of Holocaust survivors and how knowing their story helped her understand their obsessive need for control. I loved the account of her first recital, when her father springs on to the stage with a pocket knife to make a hole in the floor for her endpin, her mother calling out ‘Jaaannaaatte! Your Daddy made a hole!’ as she walks on stage.

The book could have ended two thirds through, once her parents’ story has been told. But the author takes us further, through her own personal tragedy of having to leave the Minnesota Orchestra after 32 years as associate principal cellist because of hyperacusis (the inability to tolerate loud sounds) and having to conjure up some of her parents’ grit to restore her playing and forge a new career. Reflections on racism and antisemitism bring us full circle to where the book started.

JANET BANKS

No comments yet