Andrea Zanrè reviews Leonardo Cella’s book on ’Violin Making in Romagna: Masters, disciples and followers in the second half of the 20th century’

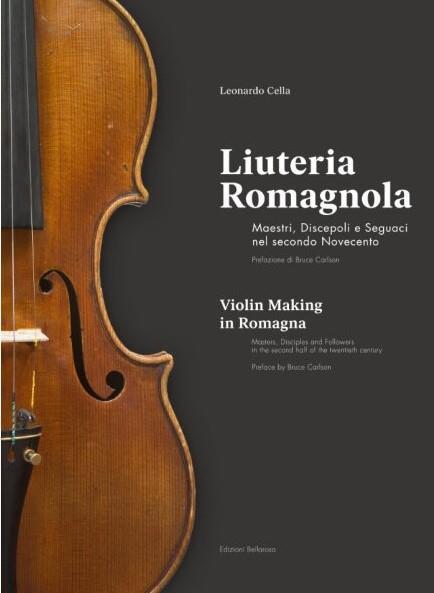

Liuteria Romagnola

Violin Making in Romagna: Masters, disciples and followers in the second half of the 20th century

Leonardo Cella

124PP liuteriaromagnola.it

Edizioni Bellarosa €250

Over the past few decades, research into 19th- and 20th-century Italian lutherie has shown that its appeal lies more in its regional diversity than in its adherence to the classical Cremonese violin making style. This new volume continues this approach by examining a school that has until now been mostly forgotten, or merged within the wider field of Emilia-Romagna violin making. However, the region of Romagna (the territory south of Bologna) shows specific trends and a taste that evolved independently from what was happening in the main city of the region, and therefore deserves more attention.

The author, the young violinist and researcher Leonardo Cella, is clearly in love with his subject. A native of Pesaro, not far from the southern border of the region, he is thus an ‘adoptive son’ of Romagna, and his interest grew from meeting some of the luthiers who were active there in the second half of the 20th century. These make up the focus of this volume.

The book opens with an inspired account of Cella’s fascination for this territory. He then differentiates between the ‘masters, disciples and followers’ active in the region. In the first category, he includes four makers well known to the wider audience: Marino Capicchioni in Rimini and Arturo Fracassi in Cesena; then the perhaps slightly more neglected character of Primo Contavalli in Imola, and Giuseppe Lucci, a native of Bagnacavallo. This is a small town that used to be one of the centres of Italian violin making, for decades hosting a national competition under the auspices of Lucci himself.

All of these makers were mostly self-taught, as were the vast majority of the lesser-known names that form the subsequent section of the volume, a dictionary of instrument makers from Romagna that extends from the end of the 19th century to the present day. In some cases both these masters and their followers show interesting connections to other contemporary Italian makers, such as the Pollastri family in Bologna, the Bisiach family in Milan, and Simone Fernando Sacconi, among others.

Read: Carlo Bergonzi was never a wealthy violin maker – but he still used the best-quality maple ever seen

Book review: I Segreti di Sgarabotto

The photographic section of the book focuses only on the luthiers active around or after the mid-20th century, grouped according to the leading makers listed above; the connections between them rarely involve a master–pupil relationship, and are mostly indirect connections. This makes the style of the ‘followers’ less distinctly adherent or influenced by the ‘masters’ but on the other hand is the reason for the naivety and spontaneity of their work. The illustrations are of fine quality, and all the violins, including those made by the lesser-known makers, are reproduced full-size. These are rarely encountered either on the market or in the auction sales, so the book will be a useful reference to their work for enthusiasts and collectors.

ANDREA ZANRÈ

No comments yet