Tully Potter reviews Michael Brittan’s picaresque account of the superstar violinist’s tour of South Africa

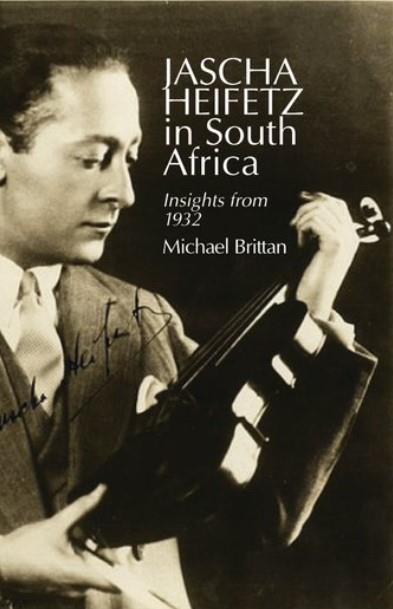

Jascha Heifetz in South Africa: Insights from 1932

Michael Brittan

320PP ISBN 9781576473535

Pendragon Press $48

It could be interesting to have a ‘bow-by-bow’ account of a Heifetz tour, but this book leaves me feeling frustrated. The author, a South African violinist and engineer based in America, keeps going off-piste and dragging in extraneous waffle, so that his main subject is often submerged.

You have to wade through a lot of Heifetz guff: he is the only violinist I can think of whose fans feel a constant need to elbow you in the ribs and tell you how wonderful he was. Michael Brittan is clearly a paid-up member of the fraternity. Chapter 1, ‘The Violinist of the Century’, gives us a dozen pages of this stuff. Chapter 2 is headed ‘The Super-Virtuoso from Vilna’ and the word ‘genius’ is routinely trotted out for Heifetz, ‘the musical God astride the Olympian peak unleashing bolts of electricity from his technical arsenal’. After a while, one feels like saying (adapting Rosenthal’s quip about a fellow pianist): ‘Yes, he was good, but he was no Heifetz.’

Billed as ‘The King of Violinists’, Heifetz slotted his sole SA visit, with pianist Isidor Achron, into his fourth round-the-world tour. Starting in Cape Town on 1 June 1932, owing to the success of his two recitals he had to give three further concerts in that city, including his only appearance with orchestra, at which he played the Beethoven Concerto. By 20 July he had given 20 concerts in 9 cities, including 6 in Johannesburg. One Durban recital was cancelled owing to Achron’s indisposition.

Heifetz got consistently good reviews and, despite the long-distance travelling, was a good sport, socialising, dancing, playing tennis and table tennis, and making contact with Jewish organisations. His wife was not with him but the local impresario Alex Cherniavsky of the well-known Odessa musical family – whose bureau organised the tour with African Consolidated Theatres – got brother Leo Cherniavsky to shepherd the two artists round the country.

Brittan seems incapable of following a chronological thread, jumping about within chapters; and surely Chapter 6, ‘South Africa in 1932’, should follow Chapter 7, ‘The Arts and Music in South Africa’, although each contains material that would better suit the other. A whole chapter is devoted to Heifetz’s interpretation of the Beethoven Concerto, which some including myself find lacking in spirituality.

The book is lavishly illustrated, but often with pictures of musicians Brittan happened to snap after a concert, such as Rostropovich, Kogan and Oistrakh, who have as much to do with Heifetz in 1932 as I do. Brittan tries to psychoanalyse the later, complex – and often disagreeable – Heifetz; and again, this kind of thing is outside his remit.

He is on safer ground when trying to contextualise Heifetz the Lithuanian emigrant: his own family went to SA from Russia. The picture he paints of the state of culture in SA at the time of the tour – and previous tours by other eminent musicians – is a valid one, but he diffuses it by carrying the story forward into the post-war apartheid era, nothing to do with Heifetz. He also insists on bringing himself into the narrative, in the modern American style.

A distinctly mixed bag, then. But those who collect books on Heifetz – and I have quite a few myself – should find enough new material here to interest them. One definite plus is that an index is provided.

TULLY POTTER

No comments yet