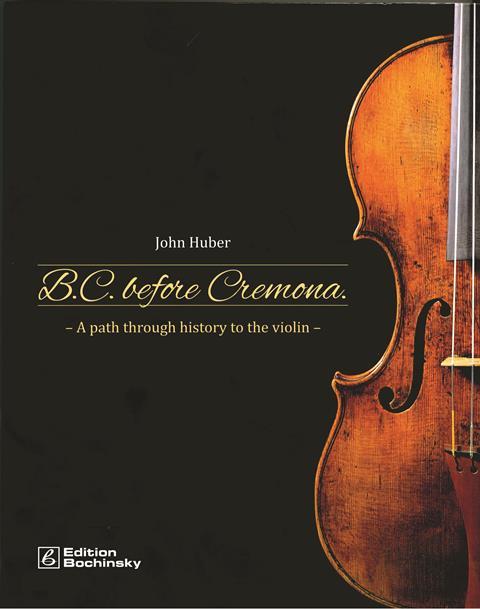

Shem Mackey review John Huber’s trawl through more than a millennium of stringed-instrument development

B.C. Before Cremona: A Path through History to the Violin

John Huber

96PP ISBN 9783941532137

PPV Medien €87

The origins of the violin have long been a source of fascination for anyone connected to the instrument. It has traditionally been considered to have been the invention of Andrea Amati in Cremona in the late 16th century. Cremona became the town synonymous with the violin and its supremacy as the home of violin making remains unchallenged to this day. Most commonly, books on the history of the violin will begin in this city and chart the development of the instrument through to the genius that was Stradivari and up to the present day. But what of the ‘pre-history’ that led to the point where Amati, Gasparo et al brought into being the instrument that we still recognise today as the embodiment of physical and musical ‘perfection’?

In this book John Huber seeks to answer that question. He has identified a series of pivotal points in world history that created the different technological and musical pathways leading eventually to Cremona.

The ‘big bang’ of bowed stringed instruments was the moment that the bow was first applied to the string of a plucked instrument. The place was most likely the Eurasian steppes where horses were first domesticated in the fifth century. The development and spread of the technique of bowing was quickly disseminated along the Silk Road and found its way via many tributaries to China, India, Persia, south-east Asia, Egypt and of course westwards to Europe. During the Middle Ages the Islamic world spread from the Iberian peninsula to the Indian subcontinent. The development of musical instrument technology is deeply connected to this geographical expansion. A new style of instrument construction was brought to Spain in the ninth century and the profession of instrument making was born.

Huber describes the impact of the extraordinary year of 1492 and its effect across Europe: Spain finally managed to overcome Granada, the last Islamic area in the country, and subsequently banished all Muslims and Jews. They fled to the Netherlands, France, Turkey and Italy and after them came a major redistribution of ideas, wealth, technologies and contacts. This shift is seen in places like Füssen, which went on to export its products and, more importantly, its instrument makers to all corners of Europe.

This is a history book that places the origins of the instrument in a very real geographic and cultural context where the main protagonists are identified. Huber has laboured with care to produce a volume that fills many of the gaps in our understanding of the prehistory of violin making. It takes us to places that are unfamiliar but inevitably lead to an increased understanding of the very familiar instruments that we make and play.

This book is an enjoyable read, laid out in two-column pages peppered throughout with maps, illustrations, paintings and pictures of instruments that may be new to many – the ancestors of lute, viol and violin. The footnotes are excellent and provide invaluable support to the main text.

SHEM MACKEY

No comments yet