Despite being a ‘non-violinistic’ piece, the Brahms Violin Sonata no.1 stands out for the French violinist as the work that helped him discover the wonders of chamber music

Brahms is the central composer in my life. I love his Violin Concerto and all the chamber music, which I’ve played many times, but the piece that first got me interested in him was the First Violin Sonata. I first heard it on a recording when I was very young; I can remember that it felt like listening to poetry from the very first note to the end. When I was twelve years old I persuaded my teacher Veda Reynolds to let me learn the first movement. She told me how difficult it was, but a week later I played it for her, and asked ‘If I wanted to perform it this summer, what would it need?’ She looked at me with big eyes and said: ‘Time.’ Whenever I’ve played it in the past three decades, I’ve remembered what she said, and I think it always gets a little better because I’ve developed a little bit more – and I think I’m finally beginning to understand what’s happening in the piece!

‘The First Sonata has always been at the centre of my musical life’: Renaud Capuçon’

At that age, most young players want to learn the Third Sonata as it’s much more of a virtuosic showpiece. For me, though, it was the lyrical theme of the first movement that captivated me, like listening to a lied – as so often in Brahms, it has incredibly simple melodies that instantly make you feel better. Unlike the Third, it never allows you to show off. If you try, you’ll be found out immediately. That said, you can always hear the soul of the player shine through: you can tell the way they produce the sound, how they’re reacting, and how they’re following the lines of the piece. There are only a few works, such as Beethoven’s Violin Concerto, that have this quality. It shows that we’re there to serve the composer, not to put our own ego front and centre. And if it were possible, I’d make it illegal to play it that way!

Playing the sonata has taught me a lot about chamber works, which is the route through which I discovered all other music. It’s always been at the centre of my musical life, and I’ve carried that sensibility into everything else I’ve done. I always play concertos based on that relationship of give and take with the orchestra, rather than delivering a lecture to the audience. And I’ve always learnt something from everyone I’ve collaborated with, such as Isaac Stern who advised me to treat every performance of the Brahms like a theatrical piece: to go on stage confidently, not be afraid and never make excuses.

I often speak to young violinists practising the sonata and realise that although they know the piece very well, they have no idea about Brahms’s earlier or later compositions. My advice would be to listen to his piano works, the German Requiem and anything else they can find, to learn the environment of the piece, which also helps to put yourself completely in the service of the piece. I’d also advise working with the pianist as soon as possible. Even though I’ve played it so often, I never instruct a new pianist to play it a certain way – I listen to what they have to propose. Nowadays I play with a lot of young people, and straight away I’ll know if I’d be able to play with them for the next 20 years. When you find a musician who can also listen to you, you get a discussion going – and that can produce something wonderful.

INTERVIEW BY CHRISTIAN LLOYD

-

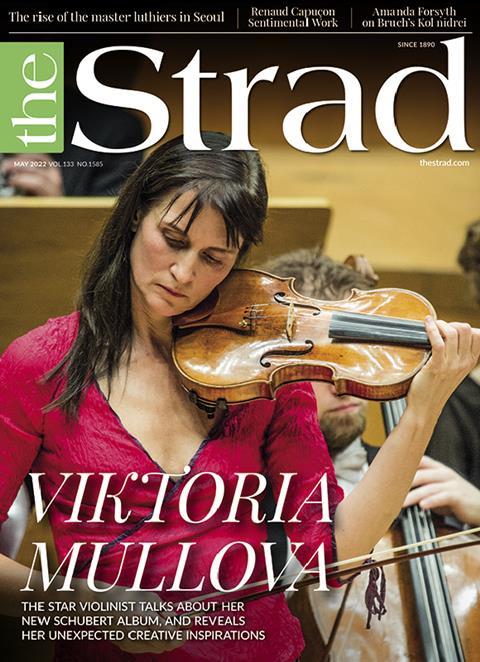

This article was published in the May 2022 Viktoria Mullova issue

The violinist discusses her latest Schubert recording with Toby Deller, as well as her collaborative projects with friends and family, and her love of improvisation. Explore all the articles in this issue

More from this issue…

Read more playing content here

-

No comments yet