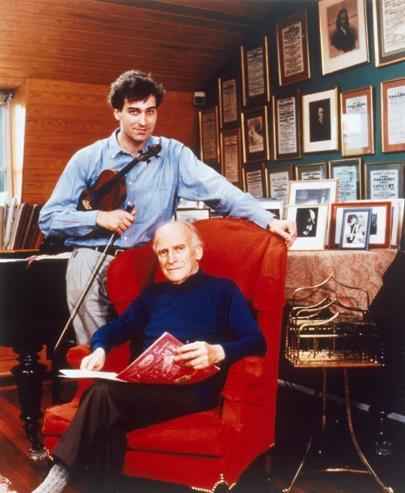

For the Elgar Violin Concerto, the French violinist has taken advice from Yehudi Menuhin, Josef Gingold and Roger Norrington – as well as the composer’s original manuscript

When I was seven years old I heard my first Yehudi Menuhin record. It was a disc on which he was talking about his life, interspersed with excerpts from some of his most famous recordings. I’d only just begun to study the violin myself, and I became very familiar with all the pieces on the LP but it was the Elgar Violin Concerto that really stood out. I already knew I wanted to be a violinist, but possibly this recording, and the Elgar in particular, put me on the path to becoming a soloist.

When I arrived at the Paris Conservatoire, I found we were expected to play the likes of Vieuxtemps, Wieniawski and Saint-Saëns – no English music, and certainly not the Elgar Concerto. But I was so desperate to play it that I ended up learning it on my own. Then I went to the US to study with Josef Gingold, who’d studied for two years under Eugène Ysaÿe. He told me how Ysaÿe had spent time working with Elgar on the piece, and how he’d given its German premiere in Berlin. He even gave me Ysaÿe’s marked-up version of the score, which I still have. It was interesting to see how often Ysaÿe had written ‘nobilmente’ below the music – one of Elgar’s favourite notations, which obviously meant a lot to him!

When I was preparing to record the concerto for Avie, with Vernon Handley conducting the Royal Liverpool Philharmonic, I researched its history and found out how much Fritz Kreisler had worked with Elgar on the original score, simplifying some passages while making others more virtuosic. Then in the British Library I discovered the score used for the world premiere performance, given by violinist Billy Reed as part of the 1910 Three Choirs Festival. There was something genuine about this version that fascinated me, seeing Elgar’s original vision before Kreisler moved in. Several parts are much harder and less violinistic, although Elgar was a violinist himself. I also gave the concert premiere of this version at the 2010 Festival to mark its centenary, with Roger Norrington conducting. He was keen to capture the tone of the orchestra as it would have been in Elgar’s day, and explained how the musicians would have sounded different. I recall how he asked me to play a passage in the slow movement ‘more expressively’, by which he meant without vibrato. Aesthetically this was very different from what I’d have chosen, but it gave the whole movement an air of sincerity.

Once, in a hotel room in Paris, I had a three-hour lesson on the concerto with Menuhin. We went through every detail of this huge piece, which took time because Elgar had written how almost every bar should be played! Both Menuhin and Norrington insisted on keeping up the tempo so that the music would flow, and so the sense of direction was always clear.

I’m glad to see that this work is becoming more popular nowadays, with more performances and recordings being made. As one of the longest violin concertos, it takes a lot of stamina but it’s worth it. In some ways it’s more like a symphony with a principal violin part, rather than a concerto: by the final movement you feel like you’ve been through a whole voyage, not only through the piece but through 200 years of violin playing. Being a very late Romantic work, it feels like a hymn to a lost world that existed before the First World War: an ultimate farewell to the lyricism of the 19th century. The violin part is so expressive that there’s a sense of being in touch with the whole history of violin playing, embracing Kreisler, Ysaÿe, Menuhin and all the great players of the past.

INTERVIEW BY CHRISTIAN LLOYD

-

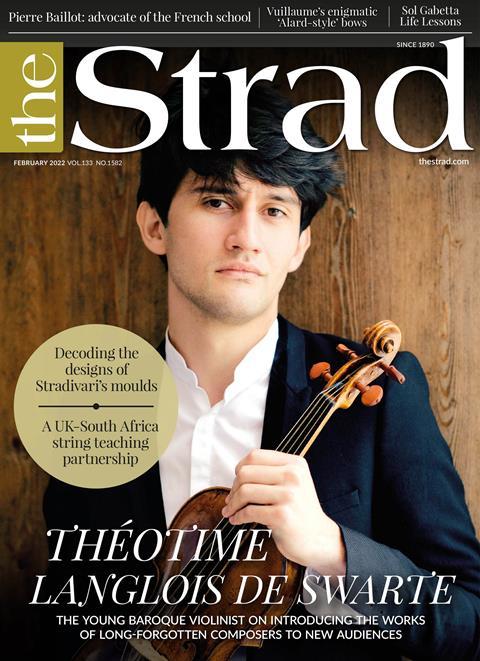

This article was published in the February 2022 Théotime Langlois de Swarte issue

The Baroque violinist’s career has taken off in the past year. Charlotte Gardner talks to him about his quest to popularise the works of long-lost composers. Explore all the articles in this issue . Explore all the articles in this issue

More from this issue…

- Théotime Langlois de Swarte

- Vuillaume’s ‘Alard’ Bows

- Pierre Baillot

- United Strings of Europe

- Cremonese Violin Moulds

- Arco Project

Read more playing content here

-

No comments yet