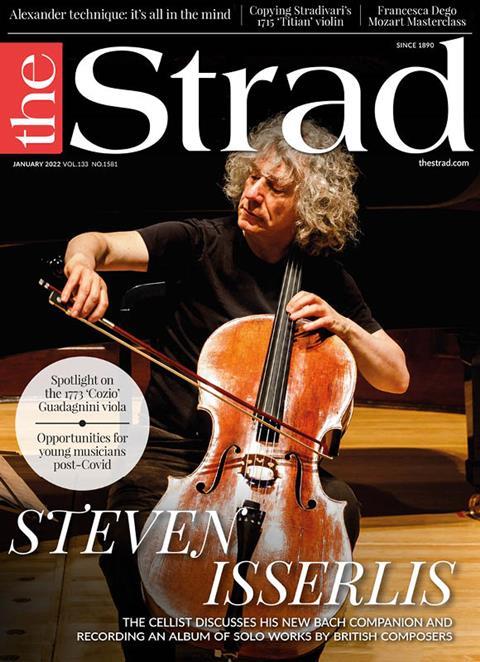

The January 2022 cover star speaks to Charlotte Smith about studying the Bach Cello Suites in the form of his new companion book, as well as performing during the pandemic

The following extract is from The Strad’s January 2022 issue feature ‘Steven Isserlis: Instinctive Performer’. To read it in full, click here to subscribe and login. The January 2022 digital magazine and print edition are on sale now

British cellist Steven Isserlis isn’t ‘just’ a musician; he’s a scholar too. While some of us failed to put the lockdowns of the past two years to good use, Isserlis completed several projects, without which, he admits, he would have gone into a ‘complete depression’. The first of these is his companion to Bach’s Cello Suites, recently published by Faber (and reviewed next issue): a highly readable pocket-sized volume, cleverly featuring important detail and advice for professional musicians while also providing clear, accessible and, above all, interesting insights for novices.

Key to the companion’s success is the great affection and reverence that Isserlis himself has for the Suites. Famously reluctant to perform the works in public for fear of memory slips – ‘I should shut up about that really; I’ve now managed to make my friends Thomas Demenga and Mischa Maisky petrified about it too!’ – Isserlis is entirely committed to investigating the intricacies of the four existing manuscripts. Not one is written in Bach’s own hand, which makes the quest to find a definitive version all the more compelling – and no doubt accounts partly for the otherwise venerable and confident musician’s fear of performing the works for an audience. ‘Basically, I practise the Suites from memory,’ he says. ‘But then I want to continue studying the manuscripts – and remembering the notes is one thing, but remembering all the articulations in four different versions is another!’

That the lockdowns afforded Isserlis the chance to devote his keen investigative talents to the Suites is great news for audiences and musicians – for although it’s unlikely the majority of us will be treated to a public performance by him any time soon, the companion presents his attitude to the works in an equally compelling form, especially when enjoyed in conjunction with his recording of the works released on Hyperion in 2007. And in fact, it was lockdown’s ability to strip performing of all its usual anxieties and expectations that enabled Isserlis to perform Suites nos.1 and 3 for the first time in years for small audiences at the Fidelio Cafe in London in July 2020. ‘At Fidelio, the audience comprised just 25 people and their mindset was different from usual,’ he says. ‘People hadn’t heard live music for so long, and were so happy and grateful for the experience, so there wasn’t any pressure.’

There is something innately ‘comforting’ about these works, Isserlis continues, which made them particularly appropriate repertoire for the pandemic. Similarly, Pablo Casals, their first great advocate, had turned to them under the looming threat of World War II, and as the Spanish Civil War tore apart his homeland. ‘There is such wisdom behind them. They’re very soothing – exciting though they are, and funny and tragic. But there’s something reassuring about their simplicity and intimacy,’ he says. As such he approaches them in an ‘instinctive’ way, as ‘all great music is natural’. This is not to say, though, that one shouldn’t also treat them with interpretative rigour. ‘I educate myself as much as I can,’ he explains. ‘I study and analyse them. But I never try to go against my instincts. Instead, you should keep educating your instincts.’

I get the impression that the extremes of historically informed performance don’t sit easily with Isserlis, though he’s particularly withering about those who adopt Baroque instruments and bows yet continue to perform the works on steel strings – something he would never do on his ‘Marquis de Corberon’ Stradivari, on loan from London’s Royal Academy of Music: ‘I see colleagues who tune their cellos down to Baroque pitch, and maybe use a period bow, but they’re playing on steel strings, so I give them a hard time. These are my friends, of course!’ he laughs. ‘But for me, the sound world is very different with steel strings. There are many more layers and so much more depth from gut. I’m not saying that I wouldn’t ever listen to a performance of Bach on steel strings – I would, and I might enjoy it a lot – but I can’t imagine playing Bach on steel myself. It has to be gut.’

Vibrato, too, is another bugbear – though again, Isserlis prefers to use his intuition more than to be dogmatic. ‘I’m not conscious of playing with less vibrato in Bach, but it just happens; and in Haydn, too. I find myself using less vibrato because that best conveys the emotions I want to express,’ he explains. ‘I certainly don’t play senza vibrato. That’s ridiculous, as there’s so much evidence that vibrato was used in Bach’s time – and it does drive me mad to see modern players using steel strings, switching off vibrato and thinking they’re playing authentically. Apart from anything else, you need to know how to use the bow properly. It can sound just awful if you don’t know how to make the strings vibrate properly with the bow. It’s about shading.’

But, as with all the cellist’s pronouncements, there’s a self-deprecating caveat at the conclusion: ‘Occasionally, I forget and vibrate too much,’ he admits. ‘I remember playing Haydn with Christopher Hogwood and the Academy of Ancient Music. At one point he turned to me and said very gently, “Is it Shostakovich?” Sorry! Sometimes I do get nervous or overexcited and vibrate excessively.’

Listen: The Strad Podcast Episode #20: Steven Isserlis on consulting musical editions and manuscripts

Read: Steven Isserlis: Instinctive performer

Read: Steven Isserlis: British Solo Cello Music

Read: ‘It’s important to be emotionally authentic – you mustn’t give false messages’ – Steven Isserlis

-

This article was published in the January 2022 Steven Isserlis issue

The UK cellist discusses his new Bach companion and recording an album of solo works by British composers. Explore all the articles in this issue . Explore all the articles in this issue

More from this issue…

- Steven Isserlis on Bach and British composers

- 1773 ‘Cozio’ Guadagnini viola

- Alexander technique: it’s all in the mind

- LGT Young Soloists record Philip Glass

- Copying Stradivari’s 1715 ‘Titian’ violin

- Opportunities for young musicians post-Covid

Read more playing content here

-

No comments yet