The British ensemble shares its thoughts on the pairing of works by Elgar and Fauré, ahead of its upcoming album release on 16 May

Read more Featured Stories like this in The Strad Playing Hub

The Eusebius Quartet’s latest release is an unusual but exciting pairing of two string quartets by British and French contemporaries Sir Edward Elgar (1857–1934) and Gabriel Fauré (1845–1924). It also includes a collection of shorter gems transcribed for string quartet by the British composer, arranger, and pianist Iain Farrington. These comprise Elgar’s Carissima (originally composed for small orchestra) and selections from Fauré’s Piano Preludes: Nos. 4, 8, and 9.

Elgar and Fauré met once at the time of the London premiere of Elgar’s First Symphony in 1908. Although Fauré spoke no English and Elgar’s French wasn’t exactly conversational, it’s interesting to compare the musical language of their two quartets, both in the key of E minor, and written late in the composers’ lives.

Ill and depressed by war-time London in 1918, Elgar completed his String Quartet, Op. 83. It is cast in three movements, the outer Allegro movements bookending one marked Piacevole (poco andante). This slow middle movement, which contains a quotation from Elgar’s Chanson de Matin, was a favourite of Lady Elgar. It was played at her funeral in 1920.

Gabriel Fauré composed his only String Quartet, Op. 121 in 1924, shortly before his death at the age of 79. By this time, he had been totally deaf for some years, and the quartet suggests a mind driven within itself in a way that hints at Beethoven’s Late String Quartets.

This final work of Fauré presents an extraordinary duality, which masks the romantic ideas of his earlier music with what the English composer and writer Robert Matthew-Walker calls ’a soft steely twilight that at times appears almost menacing.’ As with Elgar’s quartet, the central Andante movement particularly captures the imagination with its musical colouration suggesting a world of halflights.

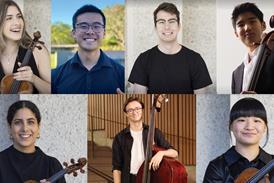

The Eusebius Quartet, comprising violinists Beatrice Philips and Sofia Kolupov, violist Adam Newman and cellist Hannah Sloane, shares its thoughts on this pairing of composers and their works, which will feature on its new album on SOMM, out 16 May.

How would you compare the musical language between the two quartets? They are both in E minor - what else do they have in common or sets them apart?

Both quartets are in three movements, and both wend their way unexpectedly to E major in the finales. Both have a kind of patience in the writing, Fauré never hurries his harmonic journeys, which often take the listener to the most extraordinary keys and places.

In this, the slow second movement of the Elgar quartet shares a certain style. It also has a type of meditative quality, totally unhurried and ruminating on single chords for many bars, with only tiny changes happening slowly - Alice Elgar, for whom this was her favourite of all her husband’s works, described it as ‘like looking at sunlight refracted through a prism’. But this is probably where the similarities between the two pieces end. Fauré’s language is more harmonically abstract at this point, where Elgar’s is wistfully melodic.

We played both quartets together in a series of concerts in 2022, and we were amazed by how well they framed each other; two contrasting works from the same era, both with a certain nostalgic flavour communicated in their own unique language. Audiences loved hearing the two together, which was what sparked the idea for the CD. We then discovered that Fauré attended the premiere of Elgar’s first Symphony in 1908 and professed to ‘admire him greatly’. Knowing how Fauré’s music was also hugely popular in Britain at this time was also very inspiring and spurred us on in exploring this previously uncharted pairing.

Can you comment on the poignant themes regarding both quartets - particularly how Elgar’s was written during the war, while Faure’s a few years later shortly before his death. How is this reflected in the string writing?

Both works were late, if not last works for Fauré and Elgar. Neither had completed a string quartet before, both revering and rather fearing the format. (Elgar had had a go many years previously but abandoned it to complete his first symphony).

Elgar’s string quartet was composed over the course of 1918-1919, receiving its first performance in May 1919. At a time of personal struggle, (in early 1918 Elgar was recovering from surgery) and of great national turmoil at the end of the First World War - it is perhaps surprising that this was a year of such productivity for Elgar. His violin sonata, piano quintet and cello concerto were completed in the same year as the string quartet, three out of the four works sharing the brooding key of E Minor.

The sense of poignancy, loss and a longing for a lost world permeate all these works, and none so more than the string quartet. It’s rather serene and chorale-like opening is almost immediately interrupted by an accelerando, rising in dynamic to the upper registers of the first violin, before melting back down and into the most heart-felt and touching second subject theme. All the turmoil and emotions of what was happening at this time, Elgar has poured into this music.

For Fauré too, his quartet seems to form a kind of farewell. While his harmonies are radiantly experimental, typical of his late style, he also references music from much earlier in his career, as if wishing to draw together the threads of memory. The opening viola line, a sparse ethereal line of plainchant which is harmonically ambiguous (perhaps harking back to his childhood days in church) is directly followed by an earth-bound and heart-felt answering phrase in the first violin that quotes from his beautiful op.14 violin concerto, composed decades earlier.

One result of the string quartet being composed so late in Fauré’s life is an absence of expressive instructions in the score: Fauré died before he could complete the markings, having managed only the first couple of phrases. Although his student was given the task, resulting in the Durand publication, we felt there was an opportunity here to carefully interpret Fauré’s writing ourselves, coming up with something of a hybrid between the Durand and the more recent Barenreiter editions. It was extremely interesting to identify the harmonic similarities here and there to his other chamber-music works and then to use our knowledge and experience as performers to interpret and decipher some of the more abstract elements of the quartet writing.

Tell us a bit more about playing the transcriptions of Faure’s piano preludes. What does the string quartet instrumentation bring to the table?

The Nine Piano Preludes, op.103 (1910) are from Fauré’s later period, like the String Quartet. We were particularly drawn to these pieces because, like the quartet, they show so clearly Faure’s ability to make the seemingly simplest turn of phrase relate something extraordinary. Sometimes even a single note can utterly change the content of what you’re hearing, as if helping the music turn a corner to see a whole horizon anew.

We were inspired to ask Iain Farrington to make a transcription for string quartet of numbers 4,8 & 9 because in these preludes the piano writing seems to particularly celebrate the independence of each line (often between the right and left hand), so what is exciting about a quartet transcription is that it extends the possibilities even further. The slow music in particular has a legato quality throughout, especially in the bass line, which lends itself perfectly to smooth and beautiful cello playing.

The Eusebius Quartet’s new release of Elgar and Fauré Quartets is out on the SOMM label on 16 May 2025: https://listn.fm/elgarfaurestringquartets/

Read: ‘An emotional journey’: Alexander Sitkovetsky on Strauss’ Metamorphosen

Read: Session Report: cellist Zlatomir Fung on recording operatic fantasies for his debut album

Read more Featured Stories like this in The Strad Playing Hub

The number one source for playing and teaching books, guides, CDs, calendars and back issues of the magazine.

In The Best of Technique you’ll discover the top playing tips of the world’s leading string players and teachers. It’s packed full of exercises for students, plus examples from the standard repertoire to show you how to integrate the technique into your playing.

The Strad’s Masterclass series brings together the finest string players with some of the greatest string works ever written. Always one of our most popular sections, Masterclass has been an invaluable aid to aspiring soloists, chamber musicians and string teachers since the 1990s.

The Canada Council of the Arts’ Musical Instrument Bank is 40 years old in 2025. This year’s calendar celebrates some its treasures, including four instruments by Antonio Stradivari and priceless works by Montagnana, Gagliano, Pressenda and David Tecchler.

No comments yet