Adrian Smith spent a weekend in Dublin exploring the delights of Spike Cello Festival, a vibrant ‘alt-cello’ weekend that celebrates the versatility of the instrument beyond the core classical repertoire

Dublin-based Spike Cello Festival – now in its fifth edition – is a celebration of the non-traditional cello that attracts such world-class performers as Abel Selaocoe and Ayanna Witter-Johnson and straddles a dizzying array of genres.

United by a shared interest in the cello ecosystem that extends beyond the classical, Mary Barnecutt and Lioba Petrie (who are desk partners in the City of Dublin Chamber Orchestra) were inspired to set up the festival after noticing how many of their fellow cellists were exploring the instrument in unusual ways. According to Barnecutt: ‘I saw a poster outside the Royal Irish Academy of Music for the Amsterdam Cello Biennale, and there was a tiny subsection of a couple of people doing non-classical cello – and I thought, that would be great! That led us to look at New Directions, which is a non-classical cello festival in the US and we realised we had enough people to get together for a day or two just in Ireland. After this, it just spread and people started approaching us.’

Given the uncertainty as to what would be permitted after the Christmas surge of Covid infections, Barnecutt and Petrie cleverly hedged their bets for 2022’s edition – held over the weekend of 11–13 February – by scheduling a mixture of live and online events to cover every eventuality. According to Petrie, ‘Mary and I both run music series so we’ve had to juggle, reform and recalibrate. So when it came to this festival we said: “Whatever happens, we have to make this as Covid-proof as possible.”’ The strategy certainly paid off and the online dimension ensured that workshops and concerts could take place from different locations around the world, giving the festival a very international feel.

’The inventiveness of Ayanna Witter-Johnson’s accompaniments was breathtaking’

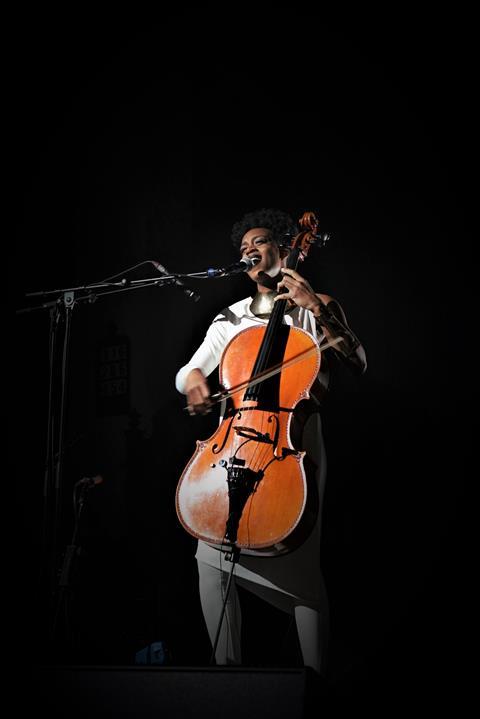

The first live concert took place at St Stephen’s Church, known as the Pepper Canister owing to the distinctive shape of its spire. The major draw here was the appearance of the festival’s headline act, the English composer–cellist–singer Ayanna Witter-Johnson, in a concert that also featured a recent composition by Irish composer Sam Perkin and a performance by the Galway-based Romanian cellist Adrian Mantu.

Soft lighting illuminated the apse of the church and a gentle haze of smoke created an intimate atmosphere, but this calm was soon dispelled by the frenetic energy of Mantu and his CelloVision project, an idea hatched during lockdown that sought to connect artists living in distant locations through video and pre-recorded material. His performance consisted of a musical journey of folk-inspired pieces that led from his native Romania to the west of Ireland and then back to Transylvania via Spain, North Africa, Italy and Israel. Among the many highlights was his rendition of Rogelio Huguet y Tagell’s Flamenco choreographed for a Spanish dancer (Anastasia Grigore), but the work that stood out for me was his performance of fellow Galway-based Irish composer Jane O’Leary’s Distant Voices (1998) for eight cellos (the other seven parts were pre-recorded). Inspired by an Irish tune that the US-born O’Leary heard when she first arrived in Ireland, this work passed through a range of shimmering textures to a final impassioned section where a build-up of vibrato in all parts created a dense wall of sound.

Perkin’sAlta (2019) arranged for two cello trios and tape arose out of a collaboration with Finnish scientist Unto K. Laine, who led an expedition that managed to capture the sounds of the Northern Lights. Like O’Leary’s piece, this one employs a range of tremolando textures, but whereas O’Leary’s fluctuate and melt, Perkin’s are more static and create an ethereal halo that seems almost physical as crackling sounds from the aurora borealis break through at various points.

Although this was Witter-Johnson’s first trip to Ireland, it turned out to be something of a homecoming as she recently found out that her great-grandmother was of Irish descent, hailing from those who had been sent to Jamaica some time in the 1800s. A clearly delighted Witter-Johnson told me afterwards: ‘She was from the Ford family, and she played fiddle and jigs, which is amazing.’ She opened her set with her songRome o, its beautifully delicate intro demonstrating her superb bowing technique before settling into a characteristically percussive and funky grove that combined ricochet and the gentle click of an off-beat cowbell. The inventiveness of these accompaniments in both rhythm and timbre was quite breathtaking, as was her ability to combine this with soulful singing. The set included several of her best-known songs, such as Nothing Less and Declaration of Rights – her cover of the Abyssinians’ classic protest song.

Listen: The Strad Podcast Episode #16: Ayanna Witter-Johnson on playing and singing

Watch: Flow My Tears - John Aram featuring cellist Ayanna Witter-Johnson

On Saturday I took off on the ‘Cellinstallation Trail’, a series of free, ‘pop-up’ concerts at several locations around the city. This began at midday with a performance by Aongus MacAmhlaigh in the People’s Pavilion at the Irish Museum of Modern Art whose combination of live playing with rich, layered backing tracks created a moving canvas for songs that dealt with everything from Tinder disappointments to the destruction of cultural monuments in Dublin. From here, it was a stroll over to The Ark in Temple Bar, where Adrian Mantu gave a colourful history of the cello to a group of spellbound kids, complete with costume changes and interactive excerpts from his CelloVision project.

Then it was time to dash over to the Hugh Lane Gallery on the Northside of the city where Finnish cellist Aki was demonstrating the unique timbre of his custom-built cello arpeggione d’amore through his own meditative compositions. He played these on the unusual, six-string, fretted instrument, which has a total of 24 sympathetic strings along its body.

My final stop on the trail was Ilse de Ziah, an Australian cellist now based in Cork, who was performing in the foyer of the National Museum of Ireland, just up the River Liffey at Collins Barracks. While the cello is not an instrument one associates with Irish traditional music, De Ziah’s playing made one wonder why this is still the case as she included several beautifully ornamented airs in her set such as Caoineadh na dTrí Muire (‘The Lament of the Three Marys’) with the instrument’s register and tone being particularly suited to this style.

In addition to the live performances, the online events peppered throughout the festival included everything from ‘Yocella’ (yoga sessions set to new cello works) and a masterclass in Indian music from Dutch cellist Saskia Rao-de Haas, to workshops on chop technique and how to practise. There was also a series of short commissions of new works that had been released several days before the festival and are available to listen to on the festival’s website (see spikecellofest.com/cello-daze).

For cellists of all descriptions – alternative, classical or both – and indeed anyone interested in exploring the world beyond core classical repertoire, Dublin indeed felt like a cello mecca for this packed February weekend.

-

This article was published in the May 2022 Viktoria Mullova issue

The violinist discusses her latest Schubert recording with Toby Deller, as well as her collaborative projects with friends and family, and her love of improvisation. Explore all the articles in this issue

More from this issue…

Read more playing content here

-

![[1st prize] Poiesis Quartet in round 3 (2)](https://dnan0fzjxntrj.cloudfront.net/Pictures/100x67/1/9/5/41195_1stprizepoiesisquartetinround32_547631.jpg)

No comments yet