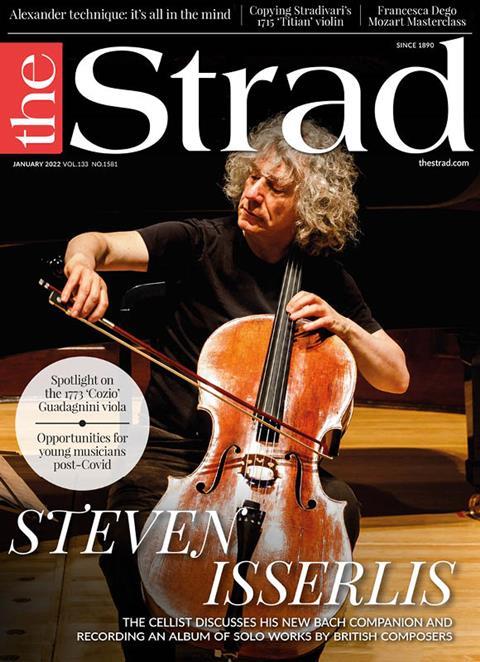

In this extract from the January 2022 issue, cellist Steven Isserlis speaks about recording works by British composers, who are all linked by a shared respect for the past

The following extract is from The Strad’s January 2022 issue feature ‘Steven Isserlis: Instinctive Performer’. To read it in full, click here to subscribe and login. The January 2022 digital magazine and print edition are on sale now

Among other smaller works, Isserlis’ recording British Solo Cello Music (reviewed last issue) features Britten’s Third Cello Suite, Walton’s Passacaglia, and Suite in the Eighteenth-Century Style by Isserlis’s great friend and mentor Frank Merrick, who gifted the forgotten work to the then teenage cellist upon rediscovering it in a box. Although Isserlis notes in his introduction that initially he saw little to connect the works on the album beyond nationality and century, he now believes they are linked by ‘a very British trait: a respect for the past’.

‘Britten’s Third Suite includes a Barcarola, a Passacaglia and a Fuga, so he’s looking back to the past. Frank Merrick is obviously looking back, and the Walton, again, is a Passacaglia – it’s a very ancient form,’ he muses. ‘Thomas Adès, whose Sola I also include on the album, has told me that essentially he’s a Baroque composer living in the 21st century. So, I guess I see more and more connections. And, in fact, as the planning and recording process went on, I remembered that I have personal connections with almost every piece. I was there for the first performance of Britten’s Third Suite by Rostropovich at Snape Maltings, and I was also there for the first performance of the Walton Passacaglia, again by Rostropovich, but this time at London’s Royal Festival Hall. And, of course, I knew Frank Merrick.’

Considering that Merrick’s work is another suite, how does it compare with Bach’s set? ‘Merrick probably heard the Bach Suites and was inspired by them,’ says Isserlis, ‘but then again, he had completely forgotten about writing the work, so we can’t date it except to say it was written before 1936, as its title page announces that it was fingered and edited by the cellist W.E. Whitehouse, who died in 1935. That was before Casals recorded the Bach Suites, so they weren’t well known at the time. But there’s very clearly the influence of Handel on the work, too.

‘What I can say, though, is that the Merrick needs to be played in a heavier style than the Bach. I remember playing the work to him and he was asleep for most of it! But at one point he woke up and told me not to double dot in his Siciliano. If I was playing Bach I would definitely double dot.’

Listen: The Strad Podcast Episode #20: Steven Isserlis on consulting musical editions and manuscripts

-

This article was published in the January 2022 Steven Isserlis issue

The UK cellist discusses his new Bach companion and recording an album of solo works by British composers. Explore all the articles in this issue . Explore all the articles in this issue

More from this issue…

- Steven Isserlis on Bach and British composers

- 1773 ‘Cozio’ Guadagnini viola

- Alexander technique: it’s all in the mind

- LGT Young Soloists record Philip Glass

- Copying Stradivari’s 1715 ‘Titian’ violin

- Opportunities for young musicians post-Covid

Read more playing content here

-

No comments yet