The Royal Danish Orchestra has been adding to its collection of fine stringed instruments for centuries – but there is revolution and evolution behind its string sound, which is unmistakable, finds Andrew Mellor

The following is an extract from an article published in the December 2019 issue of The Strad. To subscribe and read the full article click here.

A handful of orchestras foster and preserve deep-rooted playing styles that ride out generational and acoustical change. But the Royal Danish Orchestra has, in part at least, a more tangible factor at play: a collection of stringed instruments dating from a period spanning four centuries.

The principle remains, as with a number of European orchestras, that the players use instruments in the possession of the ensemble. ‘This was the king’s personal orchestra, but when opera came to Denmark and orchestras moved indoors, it became the theatre orchestra we know today,’ says Kenneth McFarlan, second violinist since 1983. ‘The king provided the musicians with the best instruments, and the Royal Theatre [the umbrella organisation of the Royal Danish Opera] took over that obligation. Over the years, the collection has grown bigger and bigger.’

McFarlan has spent some years attempting to rationalise and audit the collection of upper strings. ‘Some instruments have purported to be something other than what they are; our slowly refining expertise has proved that recently,’ he says. Many upper strings bear the stamp of Christian VII of Denmark, who reigned from 1766 until 1808, but it’s believed the stamp outlived the monarch.

Just find a double-stop, get it absolutely in tune, and it’s like the opera singer who can destroy the wine glass

What we do know is that the collection contains, in its upper strings, two each of Stradivari, Guadagnini, Storioni and Gragnani instruments. In those sections there are thirteen made in Italy between 1600 and 1800, seven from 19th-century France and two German violas from the 1600s. The cello section contains a Nicolò Amati and the bass section a Girolamo Amati II, two Panormos, a Thomas Kennedy and two instruments by John Lott I. The Royal Theatre also owns the 1741 ‘Kreisler’ Guarneri ‘del Gesù’, on permanent loan to the violinist Nikolaj Szeps-Znaider.

The crown jewels are the two Strads. The earliest is from 1691, the ‘Fletcher, Red Cross Knight’, now in the hands of concertmaster Tobias Durholm. ‘It has a very concentrated sound; Tobias finds it difficult to play in quartets with it, because it doesn’t blend so well,’ says McFarlan. The other Strad, the ‘Yoldi-Moldenhauer’ from 1714, is regarded as the sister instrument to Itzhak Perlman’s ‘Soil’.

Lars Bjørnkjær, the concertmaster who’s currently using it, picks it up to play, suggesting I listen out for overtones. ‘You don’t have to do much to get them,’ he explains. ‘Just find a double-stop, get it absolutely in tune, and it’s like the opera singer who can destroy the wine glass.’ He does this, and the overtone spectrum is clear as day. ‘When I’m in shape, it gives me what I want,’ he says. ‘It is sensitive; you have to nail it and play in tune. But it’s a daily pleasure if you treat it well. These instruments certainly contribute to the brilliance of the orchestra’s string sound.’ McFarlan adds: ‘You can almost feel it in your stomach.’

To subscribe and read the full article published in the December 2019 issue of The Strad, click here.

-

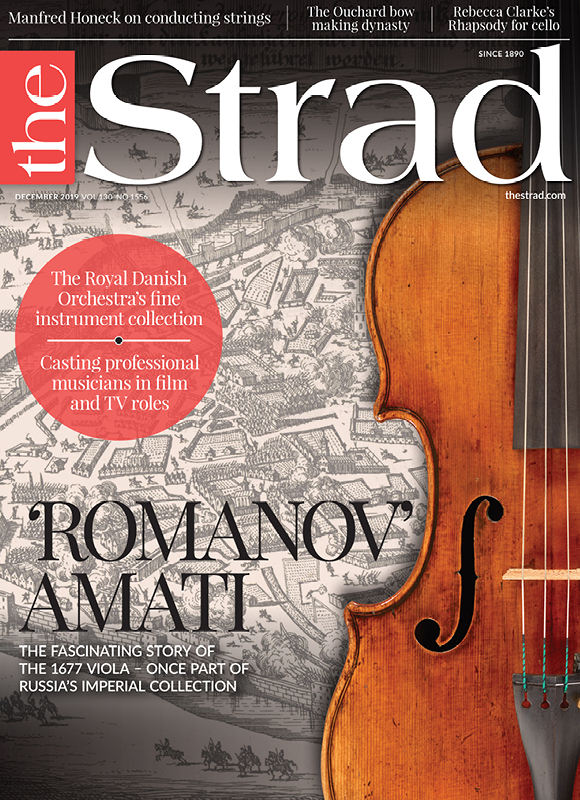

This article was published in the December 2019 ‘Romanov’ Amati issue

Exploring the fascinating story of the 1677 ‘Romanov’ Nicolò Amati viola - once part of Russia’s Imperial Collection. Explore all the articles in this issue.

More from this issue…

- 1677 ‘Romanov’ Nicolò Amati viola

- Casting professional musicians on screen

- Royal Danish Orchestra instrument collection

- Rebecca Clarke’s 1923 Cello Rhapsody

- The Ouchard bow making dynasty

- Manfred Honeck on conducting strings

Read more Playing content here

-

No comments yet