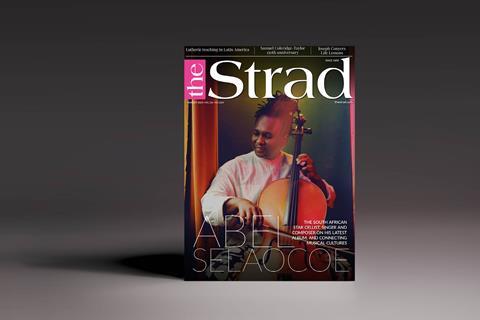

What can musicians learn from sports and ballet psychology? Violinist Emma Baird speaks to performance psychologist Britt Tajet-Foxell, with further accounts from cellist Matthew Barley and violinist Ksenia Berezina

Elite performance psychologist Britt Tajet-Foxell has worked with many of the world’s top musicians, ballet dancers and sportspeople, using her expertise to facilitate the highest levels of performance. After working as one of the first physiotherapists at the Royal Ballet Company for twenty years, she decided to retrain as a psychologist after becoming fascinated by the psychological aspect of rehabilitation. Following numerous successes, she was appointed the first ever consultant psychologist for the Royal Ballet. Britt subsequently worked with the Norwegian Olympic Team, the British Olympic Association, the English National Ballet School, the Central School of Ballet and with members of the Orchestra of the Royal Opera House.

I ask Britt if sports and ballet psychology can be directly applied to musicians too. The answer is a confident and simple yes. She elaborates: ‘whether you are a dancer, musician, athlete or in fact any kind of performer, it is always about translating that passion, motivation, potential and hard work into a physical performance, which could be a pirouette or a rowing stroke. For musicians, this may be as minute as the movement of a violinist’s fingers. The process of translation between mind and body is exactly the same, but the instrument may be different. And this is where things can go wrong: you may have the intention to play a note beautifully and softly, but a number of things could get in the way and disturb that translation process. A thought may come up which triggers a stress response and disrupts focus, for example.’

This fact poses an important question: why is ballet considerably further ahead of classical music in this field, if the psychological aspect of both disciplines is so similar? According to Britt, timing is key. It just so happened that the Royal Ballet Company, and their director Monica Mason in particular, was forward-thinking and open minded: ‘Monica was hugely interested in rehabilitation while I was a physiotherapist at the company. We often discussed the psychological component of recovery. When I returned as a newly qualified psychologist, she was on the spot and ready to promote it as an integral part of the Royal Ballet’s rehabilitation programme. We had the same vision and it was a result of the right people at the right time. Yet, there was a lot of skepticism surrounding psychology back then, and one of the first people to embrace it was Darcey Bussell. The injury aspect helped with this acceptance: dancers got into psychology through injury, which is such a common occurrence for them. They felt comfortable about using it around injury, which they may not have been if it was solely about seeing a psychologist. I often talk about using injury as a ‘springboard’ to becoming an even better performer. It opens a door into performance psychology and provides the opportunity for dancers to build strategies and resilience through dealing with it, so that the whole experience becomes beneficial.’

Arguably, this skepticism is misplaced. Elite sportspeople and artists care so much about what they do, to the point where it can sometimes consume their identity, rendering them especially vulnerable to issues such as self-doubt and perfectionism. Surely, they are the people who need some form of psychological tool kit the most. Britt agrees, saying ‘performing artists are extremely passionate about their work. It is always about pursuing excellence. One of the things I have come across is that most of them are perfectionists. People think that you need to be that way in order to become the best version of yourself. That is not true. Perfectionism can be very damaging and it traps you in your own anxiety. I would be wary of it. I promote the idea of pursuing excellence: taking small, smart steps towards always being better. The emotion around that is a sense of freedom, freedom to develop. It gives you a map with lots of different possible directions towards improvement. If your thought is ”I must be perfect”, the feeling around that is quite arresting and inhibiting. It doesn’t tell you what to do.’

Read: The Inner Monsters responsible for performance nerves

Read: 5 tips for conquering performance nerves from 5 solo string players

Ksenia Berezina, violinist in the Orchestra of the Royal Opera House, speaks to me about further stigma within the conservatoire setting: ‘I was a student once, and always felt that I would have benefited from a psychologist’s help. I think most of us would. As a student, you are not going to say ”I need some help”, because everybody is trying to show off and it’s not cool, is it? Through absolutely incredible imagery, Britt helped me to get very comfortable about what I do, and to put my focus in the right places during performances. I feel really blessed that I have met her. She is a very special person and she will just know, like a doctor, what to do.’

Regarding the recovery from trauma or injury, Britt emphasises that ‘it is incredibly important that someone who is fully qualified to deal with it, deals with it. If someone who isn’t qualified goes into an individual’s mindset and opens up a representation of a scary injury, that can do an awful lot of damage and create a panic attack. For instance, if you need to have a tooth taken out, it seems very simple just to pull it out. However, you go to a dentist to have it done: if something goes wrong, you need someone there who knows how to rescue it.’

I thought it would be interesting to hear a psychologist’s perspective on the widely discussed and debated topic of practice. Is it better to do numerous hours per day or shorter bursts of focused sessions, or is it entirely dependant on the individual? She says ‘Ultimately I think it is a personal preference, but it is what happens in the brain, what happens internally while you do it, that is going to make the difference. For instance, you could have three athletes with exactly the same technical and physical abilities, but the one who is mentally robust and has developed a mental training programme is the one that is going to end up standing on the podium. At the elite level that we are talking about here, the mental component (which, for you, is linked to musicality and artistry) is what will make the difference.’

Ksenia agrees, saying ‘It is a lot more helpful than just doing ten hours of practice. That won’t solve anything if the problem is in your head, such as thinking that people are judging you or anticipating a particular passage with fear. It’s something that we all have to overcome. Britt tells you what to do when these types of thoughts come into your head. I don’t think there are many people around who deeply understand the specifics of music psychology or performance psychology, nobody considers it.’ According to Britt, ‘regular mental training and practice is required, and one should build it in, just for ten minutes a day, as a maintenance routine.’

A prominent part of that routine, and of Britt’s work, is visualisation. I ask her to elaborate on her use of imagery with patients in order to create a clear and succinct language for their emotions. She says ‘we need to develop this instant communication system, so that we have a smart, sharp and simple way into the problem. We never have much time: I could have a musician fly in to see me from Berlin, who must fly back on the same day. There is limited time to turn things around.’

Esteemed cellist, international soloist and chamber musician, Matthew Barley, tells me about the importance of using visualisation techniques as part of his recovery from a shoulder injury. He says ‘working with Britt helped with my recovery tremendously. I came across her through my daughter, who dances with the Royal Ballet Company. One thing that we did a lot of, was visualisation. For example, I was told to imagine a TV screen in front of me and think about what would show up on the screen if I imagined myself playing with a painful left shoulder. I would see images of jagged, sharp black and red lines in my imagination. When asked what it would look like if I was playing with absolute ease and comfort, I would then see blue and green gentle, curved lines on the screen. Then, I would try to visualise myself playing with the sore shoulder while also looking at the nice blue and green screen. When I picked my cello back up, the results were extraordinary and I was astonished! I then developed a “visualisation work-out” which I still use now.

’I once asked Al Jarreau how he prepares for his performances, when we were both performing at the Abu Dhabi Festival on different days. He said that, before every single performance, he will imagine that he is looking down and watching himself perform the entire concert through, which could be two hours long! It is very powerful, the imagination.’

Read: Matthew Barley: How a skiing injury changed the way I play

Listen: The Strad Podcast #13: Dr. Renée-Paule Gauthier on dealing with performance anxiety

No comments yet