How to get the most out of your body when playing the double bass, by Dan Styffe, principal bassist for the Oslo Philharmonic Orchestra and professor at the Norwegian Academy of Music

Explore more Featured Stories like this in The Strad Playing Hub

Many string players use too much muscular force in their playing. With the bass everything is much bigger, so when we use too much arm muscle instead of weight, it creates problems with the way we use our fingers; excessive pressure kills much of the instrument’s vibrations. Among other things, this affects our string-crossings, articulation and the quality of our sound. Instead, we need to use relaxed weight (gravity), from the shoulders and back all the way to the bow. In this article, everything discussed relating to the back muscles, arm weight and playing on the ‘correct’ side of the string applies both to the French and German bowing systems. When I talk about flexibility and activity in the fingers, this too can be applied to both systems, except in the case of string-crossings, which relates mostly to the French bow.

EXERCISES

‘Relaxed’ does not mean passive. The arm and fingers should be active at all times. Many bassists bow from the arm alone, but the shoulder blades should also be active, with weight coming from the back between them. Identify the right muscles by trying this exercise without your instrument:

- Let your arms fall down by your side.

- Pull your shoulder blades together, so that your arms move behind you. Don’t use your arm muscles to do this – only the muscles in your back. Keep your shoulders low at all times. Now relax.

- Open your shoulder blades and extend your shoulders forward, again using only your back muscles and not your arms, and making sure that your shoulders stay low. Again, relax.

- This time, pull back only your right shoulder blade, then move it forward as far as possible, and relax it again. That’s the action we need when we bow. If we use these muscles as well as our natural arm weight, a lot of the work needed has already been done, meaning that the smaller muscles in the hand and fingers can focus on more intricate details such as articulation and string-crossings.

- Finally, repeat the last point with your left shoulder blade. This is the movement we use when the left hand plays high up in thumb position.

Using the back muscles and a relaxed arm with a pushing–pulling motion when bowing will give you more weight than you need, and helps you to stay flexible. If the bow arm is relaxed and you are using weight effectively and without pressing, you will feel your bass, strings and bow vibrate more freely.

FLEXIBILITY IN THE HAND

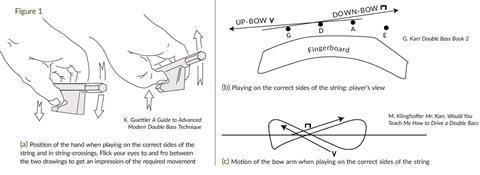

Next, consider the fingers of the right hand. It’s easier to play fast passages when using a combination of arm, wrist and fingers. Using the arm alone is much harder, especially when playing a phrase with melodic continuity or string-crossings. By letting the thumb and index finger do most of the work, we can control the weight from the arm without much muscle force at all. The other three fingers mostly follow and support, but they also play an active role in articulation and the transfer of weight from the back and arm to the bow and strings (figure 1a).

PLAYING ON THE ‘CORRECT’ SIDE OF THE STRING

If we play a down bow on, for example, the D string, the bow should be as close to the G string as possible without touching it; on the up bow, it should be close to the A string. If we do this using mostly the flexibility in our wrists and active fingers, as well as the arm, the bow will make a circular motion as we play. This makes it easier to connect to the string, to articulate and to start each note, and it makes the vibrations healthier in the bow, string and instrument.

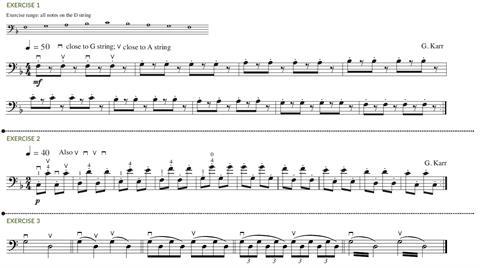

The more vibrations we produce and the more articulated the bowing required, the more important it is that we play on the correct side of the string. It feels uneconomical to begin with, but it does a lot to control vibrations and sound. Try playing on the top of the string first; then, to feel the difference, bow a few notes on the correct side of the string (figures 1b and 1c). Notes will sound clearer, the tone will be richer, and you will have better control over your attack. Begin by using a heavy attack, because it will make it easier to get the vibrations started, particularly on the thicker strings. Try practising this using exercises 1 and 2.

STRING-CROSSINGS

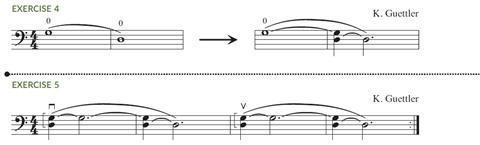

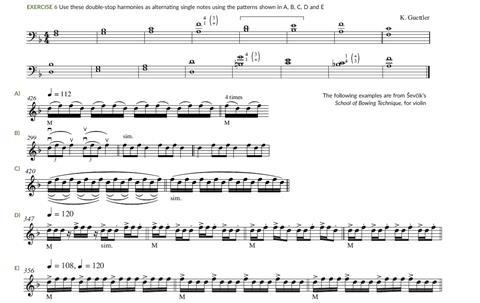

Practise string-crossings on two neighbouring open strings (exercises 3, 4 and 5). The bow should be as close to the neighbouring string as possible, the rhythm even and the movement small. The arm will move naturally if you are relaxed, but the work itself should be done mostly by the fingers, and the wrist should be relaxed. It’s easier if you play a bit closer to the bridge than the fingerboard, because the string is tighter near the bridge and moves less, so you don’t have to use as much effort. You can move further towards the fingerboard later on. When you are comfortable with exercise 3, try using the same motions for exercise 6.

TIPS FOR TEACHERS

The double bass is a very physical instrument to play. Many bassists develop back, arm, shoulder and finger problems because they play ‘wrongly’ and uneconomically. Using our fingers, back muscles and weight instead of pressure is not just about making a better sound; it is also about saving our bodies. The earlier students start using these techniques, the better. Many of the students who come to me aged 18–20 have never done them before, so we have to start from the beginning. They would have found it much quicker and easier if they had begun ten years earlier.

IN YOUR PRACTICE

Start without the instrument, to get control of your mind and muscles, and be patient. Use the shoulder-blade exercises to feel how your body, shoulders and back work, then play open strings and harmonics slowly, to identify the muscles you need. Do this for 10–15 minutes at the beginning of your practice every day. Over time, you can start to apply this relaxed use of weight to slow melodic lines, then more technically challenging ones. After a while you will find that you don’t need to think about it any more – it will become a part of your everyday playing.

Guettler’s A Guide to Advanced Modern Double Bass Technique (Yorke) and Ševčík’s School of Bowing Techniqueop.2 part 3 (Bosworth) are particularly useful for working on string-crossings

This article was first published in the November 2016 issue of The Strad. Interview by Pauline Harding

Read: ‘Free and ringing, never forced’ - Technique: Developing bow control for improved tone

Read: Technique: Smooth string-crossings

Discover more Featured Stories like this in The Strad Playing Hub

No comments yet