In an addendum to his article in the June 2023 issue, Gennady Filimonov uncovers how a 1708 Stradivari violin was mistaken for a cello, and other sundry observations

Discover more lutherie articles here

The June 2023 issue of The Strad contains an account of my search for a mysterious 19th-century collector of stringed instruments, identified in several sources only as ‘a Russian nobleman’. Upon the nobleman’s death, the collection of instruments were purchased by the British collector and dealer David Laurie (1833–97), who refers to them at length in his memoir Reminiscences of a Fiddle Dealer. This book was published by his son in 1924. During my research, I uncovered information about the instruments proving that Laurie’s memoir had a number of serious errors, as there were in subsequent writings. These mistakes have since been reproduced in several reputable publications, and I think that correcting the record once and for all will prove worthwhile.

In the chapter ‘Purchase in St Petersburg’ Laurie describes how, in the spring of 1876, he had received a letter from a lady in St Petersburg stating her late husband had left a collection of high-priced stringed instruments and that several of her friends had advised her to write to him and ask if he would be interested in purchasing them. The collection, he said, ‘included three Stradivari cellos several violins and a tenor. The king of the collection was of Strad’s best period 1712.’ Here we have the first of the errors: the cello he refers to was the ‘Bass of Spain’ Stradivari, which he knew to be dated 1713. The sales ledger in the back of Laurie’s book gives the correct date when recording its sale to John Adam: ‘Sale account on Sep. 30, 1877 – Stradivarius cello, 1713 - £437’.

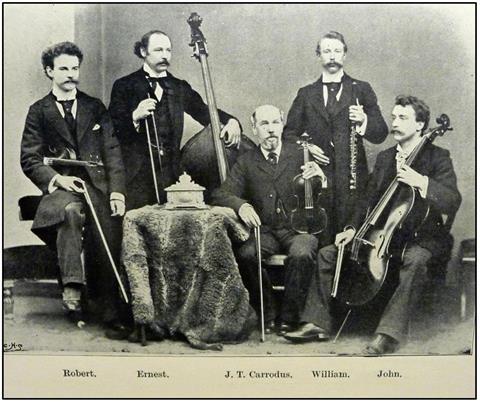

The chapter concludes with his return to London having bought the instruments, ‘My collection was soon put in order and ready for sale: one of the Strad ’cellos 1708 being bought by the late Mr. Carrodus.’ This referred to John Tiplady Carrodus (1836–95), a celebrated English concert violinist and a distinguished pedagogue. (In 1867 he was appointed as leader and solo violinist of the Covent Garden Orchestra, which he led for 25 years. He taught at the National Training School, the Croydon Conservatoire of Music, the Guildhall School of Music, the Royal Academy of Music, and Trinity College, London.) Among his prized possessions were: 1708 Stradivari violin, the ‘Carrodus’ Guarneri ‘del Gesù’, currently played by Richard Tognetti, a 1741 ‘del Gesù’ and a 1714 Guarneri ’filius Andreae’ violin. But here we have another error: the 1708 Stradivari from St Petersburg was a violin, not a cello. There is no history of a ‘Carrodus’ 1708 Stradivari cello, but certainly a 1708 violin.

After Carrodus’s death in 1895, some of his instruments were sold at auction – giving rise to some questions as to which they were. Laurie sought to clarify matters by writing to The Strad, which published his letter in full in its January 1896 edition:

THE LATE MR CARRODUS’S VIOLINS

To the Editor of The Strad:—

SIR, Observing that the late Mr Carrodus’s violins were recently disposed of by auction and as I imported both his Stradivarius and Joseph Guarnerius to this country a few particulars regarding them may be interesting and acceptable to all lovers of the violin.

As he bought the Stradivarius (1708) before the Joseph, my attention naturally turns to it first. I bought it in the year 1876 in St Petersburg along with three Stradivarius violoncellos no less and other less notable instruments all having been in the collection of a deceased amateur there. It being rather a long and expensive journey to St Petersburg it was necessary to take all precautions before I went to be as certain as possible that the instruments were right.

Fortunately, I got every assistance from the widow of the deceased gentleman who throughout acted in the most straightforward manner, and she was good enough to instruct her major domo to forward to me all the receipts and documents relative to them and as many of these bore the signatures of Vuillaume and of Gand Paris. I felt on sure ground and started without delay.

On arriving there after a wearisome and trying journey, I was much gratified to find that all the instruments were even better than I anticipated from the meagre descriptions given in the receipts. The Stradivarius of Mr. Carrodus was a fine and a grand looking violin of the great period date 1708 with this peculiarity that the table had several cracks in it which had been so well put together that they were almost indiscernible and the more so that they were all covered with the same beautiful cherry coloured varnish which the other parts had and this fact leads one to the conclusion that the repairing had been done by Stradivarius own hands.

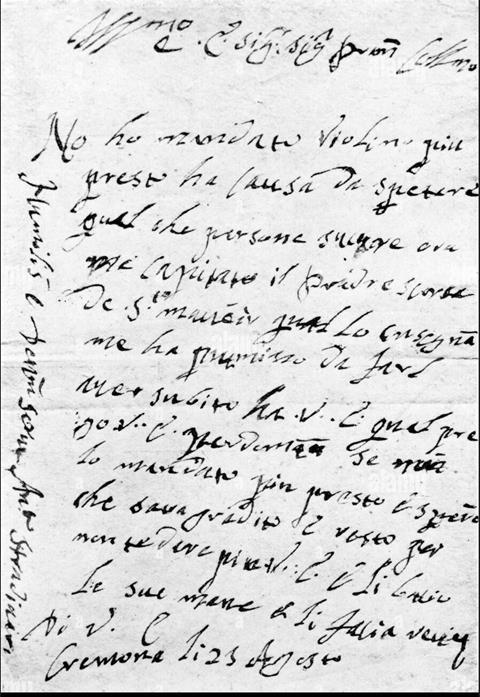

It may be interesting to note here that the only letter of Stradivarius extant and which I have seen is one in which he requests payment of one Phillip (Fillipo) for the repairing of a violin and regrets the delay in returning it to his most illustrious most reverend and dear Sir and in extenuation of such delay he blames his varnish on the repairs which seemingly dried slowly.

Would it be too great a stretch for the imagination to assume that this was the instrument referred to. Be that as it may….I then brought it (the 1708 Stradivari violin) to London and sold it to an amateur there, who gave it to a dealer (Hills) in London afterwards to sell for him and from whom Mr. Carrodus finally purchased it.

I am yours etc.

DAVID LAURIE

Ironically, while writing a long descriptive account of the instruments he purchased in Saint Petersburg, Laurie was under the impression the Carrodus fiddles were sold at the Puttick & Simpson auction of J.T. Carrodus’s instruments on 10th December 1895. In fact, the 1708 Stradivari violin was not included in the sale, as confirmed by The Strad’s editor at the end of Laurie’s letter: ‘The two instruments mentioned in [Laurie’s] letter were not included in the sale; we understand they are still in the possession of the Carrodus family. – Ed.’

Read: In focus: The ‘Carrodus’ Guarneri ‘del Gesù’

‘Fiddle Dealers Beware!’: From the archive: June 1892

The February 1896 issue of The Strad included a letter from Carrodus’s widow Ada that confirmed his note: ‘Dear Sir, Your note to Mr. Laurie’s letter with regard to my dear husband’s two instruments is quite correct. The Stradivarius [violin of 1708] has been in Mr. Bernhard’s possession some years and the Cannon Joseph [violin of 1744] is retained in the family by Mr. Robert Carrodus, both of whom are following their late father’s profession. Yours truly, Ada Carrodus.’

Laurie also mentions the famous Stradivari letter of 1708 (see translation below), connecting the ‘Carrodus’ Stradivari to it, which some future experts seemed to assert. Hubert Whelbourn’s 1937 publication Standard Book of Celebrated Musicians Past and Present stated: ‘His Stradivarius [B.M. Carrodus’s] violin was his most treasured possession, for it was supposed to have been at one time repaired by the maker himself.’

Laurie’s sales ledger recorded the sale on 30 January 1880 of a 1708 Stradivari violin for £480. After J.T. Carrodus’s death, the violin was inherited by his son Bernhard M. Carrodus (1866–1935). The Violin Times reported in 1897 that ‘Mr Bernhardt M. Carrodus has inherited his father’s Strad dated 1708, it was known under the name of Carrodus Strad during the lifetime of the artist.’ After Bernhard’s early retirement from music (due to deafness), the Stradivari went to his younger brother Robert George T. Carrodus (1875–1966). The instrument has been out of circulation since the 1880s and is not listed in any publications.

Another error that occurred in Laurie’s sales ledger led me down a false trail. The collection he bought in St Petersburg included a Nicolò Amati. I researched many instruments by that maker in old publications, and found that the one associated with David Laurie was the famous ‘Alard’ Amati, now part of the Ashmolean Museum’s collection. All of the old publications, including Laurie’s sales ledger, referred to it as c.1645. But after discovering its entire provenance, I discovered that Laurie had purchased it directly from the violinist Jean-Delphin Alard himself, at around the same time he bought the St Petersburg collection. And it subsequently turned out that the sales ledger was wrong: the ‘Alard’ Amati is in fact dated 1649. I then discovered that Laurie’s only other Nicolò Amati (from around the time he came back from Saint Petersburg) was sold to Dr Joseph Joachim on 25 May 1880 for £250. This instrument (dated 1678) had a lengthy identification process of its own, as can be read in The Strad’s June 2023 article.

Finally, regarding the ‘Bass of Spain’, referred to by Laurie as ‘the king of the collection’: in the course of my research I uncovered a source that connected the cello with the mysterious Russian nobleman Nikolai Haller himself. Peter Davidson’s c. 1895 book The Violin contains this entry on David Laurie: ‘LAURIE David Glasgow – Now living. An excellent judge of Violins and an extensive dealer in this class of instruments. Amongst the many instruments which he has imported into Britain may be mentioned the Alard Stradivarius Violin, ex: Alard Paris, the King Joseph Guarnerius Violin, ex Vicomte de Janze Paris, the Sancy Stradivarius Violin, ex the Baron de Sancy, the Haller Stradivarius Violoncello ex de Haller St Petersburg all in the possession of John Adam Esq, Blackheath London when the last edition of the present work was published and whose magnificent collection of Violins will be found detailed in the Appendix to this work.’ In the appendix, Davidson lists the John Adam collection, which included the “Antonius Stradivarius 1713 Violoncello, of magnificent tone, very handsome and quite perfect’. This publication from the ‘Gilded Age’ serves as testament to Nikolai Haller, referring to the ‘Bass of Spain’ as ‘The Haller Stradivarius violoncello’ even 20 years after his death.

TRANSLATION OF THE 1708 STRADIVARI LETTER

Most Esteemed, Very Reverend, and Illustrious Sir,

Pardon the delay of the Violin, occasioned by the varnishing of the large cracks, that the sun may not reopen them.

However, you will now receive the instrument well repaired in its case, and I regret that I could not do more to serve you.

My charge for the repair will be a Filippo*

It should be more, but, for the pleasure of serving you, I am satisfied with that sum.

If I can do anything else for you, I beg you will command me; and kissing your hand

I remain, Most illustrious Sir, Your most devoted Servant

ANTONIO STRADIVARI

Cremona August 2 1708

*Filippo - A silver coin then current in Lombardy of the value of five shillings

Read: A mystery collector: On the trail of a Russian nobleman

Read: Bow maker James Tubbs - From the archive: June 1913

Read more lutherie articles here

An exclusive range of instrument making posters, books, calendars and information products published by and directly for sale from The Strad.

The Strad’s exclusive instrument posters, most with actual-size photos depicting every nuance of the instrument. Our posters are used by luthiers across the world as models for their own instruments, thanks to the detailed outlines and measurements on the back.

The number one source for a range of books covering making and stinged instruments with commentaries from today’s top instrument experts.

This year’s calendar celebrates the top instruments played by members of the Australian Chamber Orchestra, Melbourne Symphony, Australian String Quartet and some of the country’s greatest soloists.

No comments yet