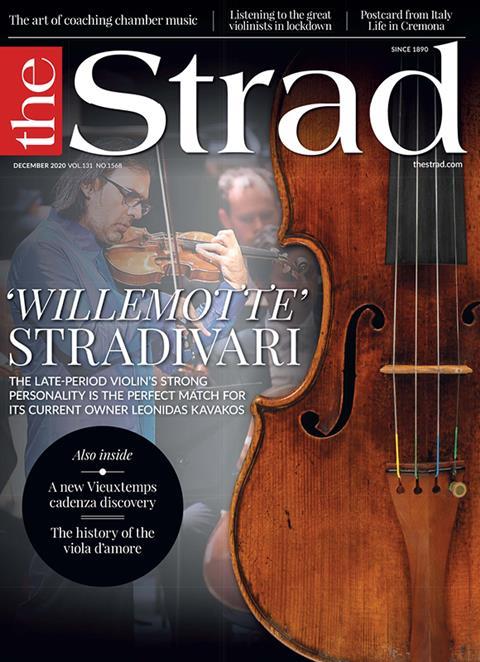

The 1734 ‘Willemotte’ bears all of Antonio Stradivari’s hallmarks including a deep, complex tone quality. Sam Zygmuntowicz examines the violin

The following extracts are from an article on the 1734 ’Willemotte’ Stradivari violin in The Strad’s December 2020 issue. To read in full, click here to subscribe and login. The December 2020 digital magazine and print edition are on sale now.

The instrument is tonally very striking. To my ears it has a transparent ‘vocal’ sound, with much detail and expressive range, dark while retaining the typical Stradivari ‘sizzle’ in the high register. The effect is almost of two violins playing in unison, with a velvet buffer in the middle range. The ‘Willemotte’ leaves one grasping for the right adjectives: complex, deep, pungent, something you almost taste as much as hear…

It has a muscular ruggedness and strong character: massive, with generous edges, full arching and broad f-holes. Its condition is quite fresh; well played and worn, but pure and with little over-coating or retouching of the varnish. The brusque workmanship, absence of thick polish, and the patina brought about by long use all make the violin feel honest and revealing…

………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………

Read: Leonidas Kavakos acquires 1734 ‘Willemotte’ Stradivari violin

I find it fascinating to trace the evolution of Stradivari construction styles and tone over time, from the intimacy of the Amatisé period, through the clarity of the golden period, the broader ‘G’ form, and finally the full-arched, deep late-period instruments. Individual instruments do vary within these periods, but one can identify the gradual development and search for perfection.

I have found the ‘Willemotte’ Stradivari a fitting subject for our current times. It demonstrates the power and durability of long training and firm tradition, in the face of adversity and age. Antonio Stradivari would have grown up in the aftermath of the famine in 1628 and the plague of 1630, and Cremona experienced multiple wars and foreign occupations during his lifetime. Stradivari would have been 90 years old when he made this violin, while his son and principal assistant Francesco would have been 63, already old for the time. Yet the waning of the precision of youth actually highlights the underlying techniques, usually subsumed in a sleek golden-period Stradivari. The resulting violin radiates nobility and a forceful personality to which we can only aspire, and a continuity with traditions that still reach out to us across centuries.

-

This article was published in the December 2020 ‘Willemotte’ Stradivari issue

The late-period violin’s strong personality is the perfect match for its current owner Leonidas Kavakos. Explore all the articles in this issue. Explore all the articles in this issue

More from this issue…

- The 1734 ‘Willemotte’ Stradivari violin

- A newly discovered Vieuxtemps cadenza

- Coaching chamber music for school-age students

- Amandine Beyer on recording C.P.E. Bach’s string symphonies

- The history of the viola d’amore

- Evolving interpretations of the great vioinists

Read more playing content here

-

No comments yet