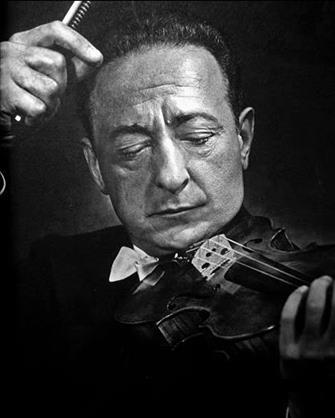

Julian Haylock considers the dazzling technique, supreme concentration and absolute clarity of interpretation that made Jascha Heifetz a unique performer

Heifetz redefined the art of violin playing. Blessed with a sensational technique and a sound of molten intensity, he left even the most gifted of his colleagues cowering in his wake. He remains the single most influential player of the last 100 years.

TEACHERS AND STUDIES

Heifetz’s principal teacher was the renowned Russian pedagogue Leopold Auer (1845–1930), who helped him make the difficult transition between child prodigy and teenage artist. Auer did very little work on technique, but since Heifetz could already play virtually anything at sight this was never a problem. Musically speaking, Auer was a facilitator who built upon each individual’s unique personality and expressive instincts. Heifetz said of him: ‘Auer was a wonderful and incomparable teacher. I do not believe that there is any teacher in the world who could possibly approach him. Don’t ask me how he did it, for I would not know how to tell you, for he is completely different with each student.’

TECHNIQUE AND INTERPRETATIVE STYLE

‘If I don’t practise one day, I know it; two days, the critics know it; three days, the public knows it!’ So saying, Heifetz disarmingly encapsulated the secret of his success. Yet if dedicated practice was all that was required, all of us who have aspired at some time to master a stringed instrument would be able to play like him. As Itzhak Perlman once pointed out, every generation produces a handful of truly exceptional players, but a violinist of Heifetz’s calibre emerges probably only once in a century.

One of the reasons Heifetz retains his unique individuality even today is that unlike the majority of modern virtuosos, his technique was based not on bel canto, cantabile legato but on a staccato bedrock that brooked no compromise. Absolute clarity was his watchword, and that is in part why he created such a sensation at his Carnegie Hall debut in 1917. Due to his taming of undue resonances, and with his rapier-like bow strokes of diamond precision, he created the impression at times of playing faster than he really was.

Heifetz retained an unusually firm ‘Russian’ hold on the bow, with the weight primarily on the index finger and the other three fingers almost totally passive. His right elbow was nearly Szeryng-like in its raised posture, and he could generate astonishing levels of sonic penetration with the minimum amount of bow by playing daringly close to the bridge. The fingers of Heifetz’s left hand were kept remarkably close to the strings and fingerboard. He used a relatively fast, narrow vibrato that involved the minimum of physical strain because it (unusually) came from the fingertips rather than the wrist or arm. The supreme precision of his left–right hand coordination resulted in a uniquely clean articulation and attack – even his expressive portamentos left nothing to chance, since they were invariably delayed to the last possible moment and executed at phenomenal speed.

SOUND

The unique intensity of Heifetz’s sound world was designed for maximum penetration. Compared with the opulent, cushioned approach of Kreisler, Heifetz emphasised the middle- to upper-frequency range, with lower-frequency resonance kept to a minimum. Whereas his fellow Auer student Nathan Milstein tended to coax a velvety cantabile from his instrument, Heifetz emitted an unvarnished, staccato brilliance. In order to gently temper the resulting brightly lit tonal transparency, he preferred the sound of plain-gut D and A strings to the high-tensile projection of wound metal. The G string was a Tricolore silver-wound gut, the E a plain steel Goldbrokat. This string choice also helps explain why he ultimately preferred the relatively forgiving nature of Guarneri violins to the more openly revealing Stradivari.

STRENGTHS

Heifetz’s impeccable technique set new standards of playing that few artists of his generation could match. His non-extraneous playing style and interpretative clarity were half a century ahead of their time, and swept aside the fusty rhetorical indulgences of the waning Romantic tradition with an electrifying frisson that held audiences spellbound.

WEAKNESSES

Some found Heifetz rather mechanical and unyielding, principally because of his unflappable interpretative persona, lack of stage flamboyance and set facial expression when dispatching even the most fiendishly demanding of passages. His supreme concentration and focus meant that he rarely sounded truly relaxed in his music making.

INSTRUMENTS AND BOWS

Heifetz’s first major instrument was a 1736 Carlo Tononi that his father gave to him, and with which he made his legendary 1917 Carnegie Hall recital. He bequeathed it in his will to his pupil and teaching assistant, Sherry Kloss. He also played the 1731 ‘Piel’ Stradivari and the 1714 ‘Dolphin’ Stradivari, which is currently owned by the Nippon Music Foundation and on loan to Japanese virtuoso Akiko Suwanai. However, Heifetz’s instrument of choice was a c.1740 Guarneri ‘del Gesù’, known as the ‘David’ because it was once owned by Ferdinand David (1810–73), leader of the Leipzig Gewandhaus Orchestra and dedicatee of the Mendelssohn E minor Violin Concerto. It was bequeathed to the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco and has been played since 2002 by Alexander Barantschik, concertmaster of the San Francisco Symphony. Heifetz owned several bows, of which his favourite was a François Tourte, although he also greatly valued a Nicolaus Kittel given to him by Leopold Auer, and bows by Dominique Peccatte, Alfred Lamy and Henryk Kaston.

REPERTOIRE

Heifetz’s central repertoire was based on the Romantic virtuoso tradition, his two signature pieces being the Tchaikovsky Concerto and Bruch’s Scottish Fantasy. Yet he was also a superb exponent of the central German classics, exchanging the furrowed-brow rhetoric commonly deployed in the works of Beethoven and Brahms for a high-tensile, super-concentrated intensity. He was in addition one of the first leading violinists to embrace the solo sonatas and partitas of Bach.

Heifetz’s quicksilver reflexes and technical fluency combined to create an uncluttered vision of even the most impassioned and overtly dramatic of scores. As he once put it, Romantic music ‘is already so overloaded with sentiment that all you have to do is play the notes – it will come out anyway!’ He also championed and recorded works that were largely neglected in his day, most notably the Sibelius, Glazunov and Elgar concertos. He once half-jested that ‘I play works by contemporary composers for two reasons: first, to discourage the composer from writing any more, and secondly to remind myself how much I appreciate Beethoven.’ Yet to his eternal credit, Heifetz commissioned and premiered concertos of superb quality by Castelnuovo-Tedesco, Walton, Gruenberg and Rózsa.

ESSENTIAL FACTS

1901 Born in Vilnius, Lithuania

1904 First lessons, aged three

1907 Russian debut playing Mendelssohn E minor Concerto

1911 Begins lessons with Leopold Auer

1912 Berlin debut playing the Tchaikovsky Concerto

1917 American debut at Carnegie Hall

1920 London debut at the Queen’s Hall

1925 Becomes a US citizen

1972 Makes final concert appearance in Los Angeles

1987 Dies in Los Angeles aged 86

RECOMMENDED RECORDINGS

Brahms: Violin Concerto RCA LIVING STEREO 82876 67896 2

Bruch: Scottish Fantasy RCA LIVING STEREO 82876 71622 2

Glazunov: Violin Concerto EMI CLASSICS 3 61590 2

Korngold: Violin Concerto RCA 09026 61752 2

Sibelius: Violin Concerto RCA LIVING STEREO 82876 66372 2

Walton: Violin Concerto RCA 74321 92575 2

This article was first published in The Strad, June 2009. Subscribe to The Strad or download our digital edition as part of a 30-day free trial. To purchase back issues click here.

No comments yet