Thomas Demenga has just released a recording of the complete Bach Cello Suites. In this article from the October 2012 issue of The Strad, he discusses his relationship with these totemic works and how to get the most out of them

This article appeared in The Strad October 2012 issue

For me, Bach is the greatest musical genius who has ever lived. His music is pure, sublime, and devoid of the melodrama of his own life’s experiences: it possesses something divine and each musician has a lifetime in which to discover new ways of interpreting it.

Even when the Swingle Singers laced his works with jazz harmonies, or Jacques Loussier’s Play Bach Trio added their own jazz improvisations, Bach’s music proved indestructible. I still recall the release of Wendy Carlos’s album Switched-On Bach in 1968, which rendered everything from the Third Brandenburg Concerto to The Well-Tempered Clavier on the Moog synthesiser. It was an experiment that many music lovers considered a crime but even then, Bach remained Bach and we simply heard his music. If you were to try this with any other composer it would most likely be unbearable. Imagine Schumann’s Cello Concerto on electronic instruments, for instance – unthinkable and a complete catastrophe.

However, for years in my recitals, I have been juxtaposing Bach’s Cello Suites with contemporary music. This month I perform the first in a three-concert series, putting the First and Sixth Suites together with pieces by Bernd Alois Zimmermann and myself. I find this form of programming inspiring, and I am quite certain that Bach would have been delighted by it – during his lifetime he was interested in all the composers of the day, and never expressed himself in a condescending way towards his peers.

BACH THE COMPOSER

Pure music seemed to pour out of Bach like a never-ending waterfall. If for some reason he could not find the manuscript he was looking for (such as his children misplacing it somewhere after playing it), he simply wrote a new piece. In addition to his many other commitments as a composer, he found time to write the Klavierbüchlein for his wife, Anna Magdalena, to improve her piano playing. He strikes me as unbelievably generous with his time. As well as organising the entirety of the music at the two main churches in Leipzig, which involved the composition of cantatas, organ preludes and chorales each week, he had to instruct the choristers in the boys’ choir in singing, how to play their instruments, and even Latin. As Martin Geck noted in his 2006 biography, Bach was considered so important to the city that he was only allowed to leave it with prior permission from the mayor.

Bach was a jack of all trades, a handyman capable of repairing anything. In my opinion, an imaginative musician should be able to do more than just play their instrument well. For example, there are string players who do not know how to set up the bridge on their own instrument, not to mention replace it. I find it fascinating to experiment with small adjustments to the bridge or soundpost of a cello, and discover the differences I can make to its sound or feel. It shows how alive and sensitive every different instrument is, and how varying amounts of pressure influence our playing. Bach possessed all these talents in abundance. He tuned his own keyboard instruments, and he played and cared for his own violins and violas, all of which he mastered. When leading an ensemble, he apparently preferred the viola because he could hear the smallest imperfections and had the best overview from that position.

Read: Looking after your instrument: the secret to bridge placement

Read: Looking after your instrument: an introduction to soundposts

RELATING TO BACH

My first acquaintance with Bach’s Cello Suites came in 1964. My cello teacher entered me for a competition as part of the Expo 64 Swiss national exhibition, for which I had to learn a few movements of the First Suite. It was one of my first real concerts, and took place in a very dark room where practically no one could be seen – not at all like what I’d been used to in Bern. I was too young to realise what a competition was, and I can remember listening to the scratchy cacophony of all the cellists in one room, practising like crazy before their performance. It made me somewhat reluctant to take my cello out of its case.

Since then, however, I have never grown tired of practising or playing the Bach Suites for my own enjoyment. When I am not feeling at my best, I go to my studio and play one or two of the suites, or sometimes all of them. They are cathartic, purifying my soul. I always feel a sense of clarity afterwards, and continue the day in a better mood. Playing the Bach Suites in concert demands the highest level of concentration, total physical relaxation, and an alertness of mind that allows one to reproduce the music, in its infinite variety, in a lively manner. It is music that speaks, informs and dances.

Anyone who believes that Baroque music lacks feeling is vastly mistaken. The so-called Empfindsamer Stil (sensitive style), which began as early as 1720, demanded that emotions and feelings be expressed, as well as frequent contrasts of mood. I am certain that people in the 18th century and the Romantic period perceived emotions just as we do today, but to express these feelings within the context of the music’s particular era, we have to use completely different playing techniques. Where Romantic repertoire asks for vibrato, rubato and a great range of dynamic, Baroque works require more subtle modes of expression, such as increased articulation, Lombardic rhythms and notes inégales. Embellishments and appoggiaturas can allow the melody to ‘sigh’, and the listener is touched directly and immediately.

Read: Historically informed performance: Baroque revolution

Read: Bach Cello Suites: What do we really know about Bach’s Cello Suites?

BACH AND GUT

To interpret Bach’s works as truthfully as possible, it is essential to play with gut strings and a Baroque bow. The cello does not have to be rebuilt in the Baroque manner – a modern instrument is able to capture the sound just as well. Playing on bare gut strings, however, goes a step further, even for musicians who are used to playing on modern gut strings wrapped in aluminium. The tone quality of a Baroque string has something ‘wooden’ and archaic: even the bowing of open strings presents a whole new sound world that cannot be compared to anything from a modern steel string. I love this sound – I always get the feeling that Bach is gazing over my shoulder with his kind, yet strict, expression.

REPEATS AND ORNAMENTATION

Some musicians have a difficult time with all the repeats in a suite’s dance movements. I love them, because whenever I play through a movement the second time, I feel as though I’m walking through a room that I have seen before in a rather weak light. This time, though, I have a torch and I’m able to discover many more details in the movement’s structure that I didn’t notice at first. I look up to the ceiling and suddenly notice the stucco. I can perceive the size of the room with more accuracy. I can walk a little faster or feel more relaxed, and maybe even stop in one spot, just to get a closer look at something – this time I feel more at home.

One should handle any use of ornaments with care. Cellist Anner Bylsma once told me he could not ‘add anything that would make this music better’, so he would rather let it be. There is certainly some truth in this, but it doesn’t mean that ornaments should never be ventured.

Read: Gut strings: A strong stomach for strings

Read: How I interpret Bach: Tomás Cotik on Ornaments, Trills and Appoggiaturas

It is better to avoid adding ornamentation in the repeats, as they stick out and it is easy to identify them as third-party interventions. However, if players add something of their own here and there in the first part, or as a transition to a Sarabande, for example, the listener wouldn’t necessarily know they were listening to ornaments at all, as they would be hearing them for the first time. There’s even the option of leaving something out the second time around, which can also have a surprising effect.

ARTICULATION AND HARMONY

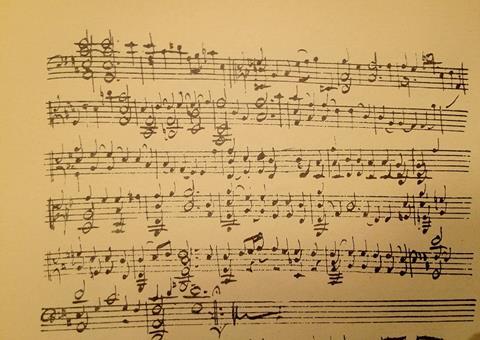

Neither the Anna Magdalena manuscript of the suites nor any of the other surviving copies from that time give a truly authentic impression of Bach’s preferred bowings and fingerings. Hence, when giving a recital, I feel able to improvise and vary my choice of both. I trust Anna Magdalena’s copy the most, of course, but with so many children to look after the whole time, she was constantly being interrupted. That would explain why there are so many inaccuracies and questions that still remain unresolved.

The articulations and spoken musical elements dictate the correct bowing

It is not the ‘right’ bowing that is crucial, but rather a clear understanding of the music in its entirety. When it comes to bowing, players are not necessarily looking for comfort and ease, nor the solution that allows them to play fluidly. In Bach’s music, it is the articulations and the spoken musical elements that dictate the correct bowing. It is also important to understand how to distribute the weights and emphasis, especially in the dance movements. False accents or too many of them are just as inappropriate as playing constant legato, which immediately gives a Romantic feel to the music.

The harmony, owing to missing bass notes and chords, has to be heard by the player inwardly, and it is not always easy to understand. For example, it often happens that one plays a note as though it were the tonic (although it isn’t), simply because the rest of the chord is not present. On this point, it is worth studying the transcription of the Fifth Suite in C minor that Bach made for lute. Listening to it, it is easy to catch oneself hearing harmony changes, usually with simpler harmonies, only to be proven wrong. The number of surprising, imaginative harmonies used by Bach in this suite is amazing. It is true that he could have used a lot more chords and double-stops, which would have eliminated all the doubts. It is very likely that, for him, it was part of some kind of exercise, or an attempt to create an entire harmony with as few notes as possible. Of course, it demands an incredible amount of analytical skill from the interpreter to play these ambiguous, non-harmonised passages with the right feeling.

THE FEEL OF THE DANCE

I have heard so many renditions of the Cello Suites that were well played but entirely missing the slightest feel for dance. It always helps right away to imagine the up-beat to a dance movement as if it were the first step on to the dance floor, rather than just a quaver before the down-beat. Then the feeling of dance is there from the very beginning, whether for a leisurely Allemande or a sparkling Courante. You often hear the Sarabande played in a tempo that is much too slow, as if it were being transformed into the suite’s Adagio. To avoid this, one simply has to imagine a leisurely pace and a somewhat larger step towards the second beat.

It is not sufficient just to know that the Allemande comes from Germany and the Courante comes from France. It is better to go directly to the source, and in this case there is none better than Bach’s contemporary, composer and music theorist Johann Mattheson, for all the information needed. His book, Der vollkommene Capellmeister, contains incredibly inspiring descriptions of each dance’s character, and since the book originates from that time period, it is a must-read for every musician interested in this repertoire.

FINAL WORDS

My main recommendation for every cellist is to play the Bach Suites as often as possible. Players should always begin from the beginning, study the manuscripts, and try out different tempos and embellishments as well as different fingerings and bowings. With all this in mind, they might indeed advance towards the heart of the music, which Bach himself claimed was his only goal.

This article was published in the October 2012 issue. Explore all articles in this issue.

Listen: The Strad Podcast Episode #20: Steven Isserlis on consulting musical editions and manuscripts

Read: Bach Cello Suites: What do we really know about Bach’s Cello Suites?

Read: Bach Second Cello Suite – Prelude: A small but crucial omission

No comments yet