Far from constricting a player’s response to a new piece, a good grounding in music theory can help them find more possibilities for playing it, as Henning Kraggerud argues

I have heard many students and musicians complain about wasting time on academic music disciplines. They often do not see the importance of music theory, and indeed, most of the time its relevance to musicians is not made clear enough to them.

Moreover, there often seems to be a battle taking place between the head and the heart; people will say something along the lines of: ‘I want to play from my heart, not pollute my musicality with this dry academic approach.’

I do believe in natural and inspired playing from the heart – but what are ‘naturalness’ and ‘inspiration’? I believe them to be gifts to a musician that pop up from their subconscious during playing.

But they have to be planted as seeds beforehand. Inspiration begins as knowledge or experience in some form, and later (after some subconscious digestion) it becomes natural enough to be used by the ‘heart’.

Music theory has always been formulated after its principles have been put into use by composers – except for twelve-tone music, where the theory came first (need I say more?).

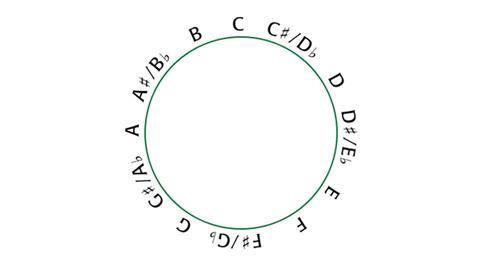

To give a practical example: it is not always apparent when practising a violin concerto from the violin part, what chord the orchestra is playing. Take the fifth bar of the solo part in the last movement of Bruch’s First Violin Concerto. Seen from the solo violin part it looks like the dominant (D major) but looking at the score or piano reduction, you see that it is in fact a B minor chord. This directly influences how to play it.

If you’re able to practise with a pianist at all times, you might absorb these types of details after a while, but to speed up the process we have a multitude of wonderful theoretical tools that create an easier path to understanding a piece even before playing or hearing it.

Music history is also important for many reasons, one being notation. Did ‘forte’ and ‘piano’ mean the same for Mozart and Beethoven as for Stravinsky? When Mozart composed a piece he wrote nothing at the beginning of the work if it started forte, as that was the norm – he only bothered to notate a dynamic if he wished it to be piano. Mezzo piano and mezzo forte are never used in the score of Beethoven’s Violin Concerto; the only written dynamics are pianississimo, pianissimo, piano, forte and fortissimo.

But there is also a kind of dynamic hidden in the chords’ relationships: within a forte section the dominants, subdominants and modulations also convey micro-dynamics, which it was not usual to notate at the time. Most players were more aware of these in Beethoven’s time, because they were composers as well.

In my ‘Practical Music Theory’ class at Oslo’s Barratt Due Institute of Music, each student looks at all the musical theories relating to the piece they will be playing at the end-of-term concert. This way, they are themselves experiencing how theory can directly improve performance and make it more meaningful.

So when people say theory is boring or irrelevant, it is easy to draw the most logical conclusion: how we currently teach it has failed to make it relevant. As a string player, next time you want to learn a new concerto or sonata, try to sit down at the piano without your instrument and then, just from the piano reduction part, start to investigate all there is to uncover and love about the harmony and structure of the piece.

Feel your way through the chords, don’t worry if you don’t know the names of their functions; just see what possibilities it gives you.

Read about the work’s composer and the time in which it was written. Listen to other types of works by the same composer (maybe operas in the case of Mozart), and only after all that, pick up your instrument. You will see that there might be better reasons to choose particular fingerings, phrasings, bowings and tempos than if you approach it from the solo part first.

You can never play a piece better than you can imagine it – but if you can imagine it better than you can play it, then you know exactly what to practise.

This article was published in The Strad July 2016 issue. Click here to subscribe and login. Alternatively, download on desktop computer or through The Strad App.

Read: Sounds good, in theory

No comments yet