Instinct isn't enough for true musicality. Instead of simply drilling technique, performers should have a profound an understanding of music theory, argues cellist David Watkin

In the last few pages of his final book, Structural Functions of Harmony, composer Arnold Schoenberg draws attention to the passing of a significant watershed in performance history: ‘Listening to a concert, I often find myself unexpectedly in a “foreign country”, not knowing how I got there; a modulation has occurred which has escaped my comprehension. I am sure that this would not have happened to me in former times, when a performer’s education did not differ from a composer’s.’

The division between theory and practice has only grown wider since then. Stravinsky’s dictum that the performer should be a ‘slave’ to the composer seemed to release players from the need to understand what they were playing. When applied to the tonal music of previous ages, playing come scritto has produced not only incomprehensible modulations, but also serious anachronisms. At conservatoires, music theory has been pushed to the margins in the minds of many young performers (and often their teachers), whose goal is to build formidable technique. After all, technical prowess is easier to measure than musicianship, and it’s generally the prime currency at conservatoires, auditions and competitions. But during the 60 years since Schoenberg’s observation, audiences have voted with their feet, seeking more authentic musical experiences in popular music, world music and – yes – early music.

Those anachronisms seldom strike you more strongly than in the world of accompaniment. Most instrumental teaching is done through solo repertoire, and the overwhelming majority of players qualify as soloists – only to go on to spend most of their time in accompanying roles. Disappointed soloists don’t make the best accompanists: ‘Oh no! Two weeks of Mozart bass-lines!’ as a friend overheard on a tour bus.

Books about great cellists finish each chapter with sentences such as these: ‘This player helped push forward the boundaries of technique,’ ‘He used his thumb further up the fingerboard than before,’ and ‘He did his bit to liberate the cello from the bass-line.’ No other subject would accept the two metanarratives at work here. The presumption of technical progress can only conclude that there was an impoverished technique in Bach’s day (why, then, write those great unaccompanied violin and cello works at all?). And there’s an obsession with soloists, solo repertoire and the aspiration to solo-instrument status – which leaves unasked the question of how the majority accompanied.

Conservatoires have done much in recent years to move away from purely solo studies to incorporate teaching skills, chamber and orchestral music, and especially audition preparation. But how can we teach students to accompany? The key lies in forging stronger connections between theory and practice. At conservatoires, Schoenberg would say, theory and harmony should have pride of place, but both disciplines are often relegated to airless basements with little connection to the rest of the institution. When I ask a group of intelligent, talented students a question about a chord, it is met with the sound of rolling tumbleweeds, or, ‘We did that stuff in the first year.’

Learning to accompany well requires and also builds a strong connection between head and heart – one that, ironically, can pay off in solo repertoire. It requires us to be, if not composers, at least de-composers – musicians who can see how the music was put together. The student who couldn’t recognise a V7 chord in their Bach sarabande (‘I’m a more instinctive player’) begins to perceive the harmonic structure, and to shape its contours, exploring new possibilities each time. Because of its different relationship between performer, composer and text, jazz has to be taught in a way that has theory-based understanding at its core.

For many in classical music, the drive for technical perfection excludes even the most dimly remembered theory or harmony lessons, as if they were vying for the same place in the brain. How can we find real meaning in a piece if we do not understand how it works? How can we be eloquent without grammar? How can groups discuss interpretation without a common language? How can we really serve the music as an accompanist if we don’t understand the challenges of inflecting those Mozart bass-lines, providing both resistance and support?

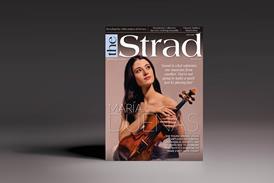

First published in The Strad, September 2013. Download the digital edition of the issue here or buy the print magazine here

1 Readers' comment