In our July 2006 issue, cellist Gerhard Mantel writes that there's more to good tone production than keeping the bow parallel to the bridge

Many years ago I realised that the traditional method of teaching sound production is limited to a scientific axiom: keep your bow in a straight line parallel to the bridge. l became intrigued by the credibility of this statement as well as by the fact that we all 'know' that the fundamentals of shaping dynamics are bow speed and pressure, and the placement of the bow on the string - but this last aspect is not entirely clear.

For instance, if the music calls for a note to be played pianissimo, I position my beautifully straight bow at the fingerboard. Let us assume that this note is followed by a rest, and the next note is forte. I pick up the bow and play near the bridge. All is well. However, what if the music calls for a crescendo to be played in a single bow stroke? If I begin on the fingerboard and quickly move my bow down towards the bridge while maintaining a 90-degree angle, I will produce an ugly scratching sound.

As I explored this problem, I asked myself several questions: Why does this happen? What happens when I deviate from the 90-degree angle? What is the possible range of deviation (bow angles)? ls there a connection between movement and deviation? ls there a difference between positioning the bow at a 90-degree angle and pushing or pulling the bow at 90 degrees?

Slow-motion photography of a vibrating string reveals that its motion is not back and forth, as it would appear to our unaided eyes. Instead, it moves rapidly between the bridge and the nut (or your finger) in complicated irregular vibration patterns that include, as partial vibrations, the whole harmonic spectrum. So when a bow slips down towards the bridge, it is moving in the same direction as the vibrations, which stops the string from freely vibrating and chokes the sound.

Let us try two experiments to see what happens if we pull the bow at a slightly slanted, non-perpendicular angle. First, with the bow placed about halfway between the fingerboard and bridge and with the tip slanted slightly down, draw a down bow, making sure the point of contact does not change. Do not allow the bow to slip up or down the string. The bow is angled. Change to the up bow, but do not let the contact point alter.

If you continue to increase the angle, you will hear the quality of tone becoming harsher until finally, when the bow is at an acute angle, the sound is so scratchy that no real tone is produced. Playing with the bow at a slight angle may, in some very intense passages, be desirable. However, you might have noted that the bow must be held rather firmly in the hand in order to keep the point of contact in place.

For the second experiment, again angle the bow with the tip slightly down. This time, allow the bow to follow its own course. The natural tendency is for the bow to drift towards the bridge. Surprisingly, now the sound is completely uninhibited, even with the bow at an extreme angle.

The bow naturally changes contact points as it moves freely between fingerboard and bridge, travelling faster or slower depending on the angle of the bow. On a down bow, the bow will slide down the string to the bridge without the slightest disturbance of the sound; and, conversely, when the tip points up (still on the same down bow), the bow moves naturally to the fingerboard. The tone is perfect because the movement of the bow is at a right angle throughout the entire experiment. Now when you make a crescendo you can go seamlessly to the bridge without risking a scratchy sound.

I recommend practising these exercises in front of a minor. Hold the bow in the 'slanted' way I've described while evenly increasing or reducing bow pressure as the bow draws near the bridge or the fingerboard. You will need to master the four combinations: down bow and up bow in both crescendo and diminuendo. Note that the greater the deviation from a right angle the faster the bow moves up or down the string. Work towards gradually resuming a perfect 90-degree angle as the change of dynamic proceeds.

A practical example of this technique is in the opening of the Dvorák Concerto. Everyone plays fortissimo on the B but finds the next two semiquavers difficult to play with the same vigour at the tip. I play the B starting at the frog quite close to the bridge and using the necessary force. A little past the middle of the bow, I gradually slant the tip up and the frog away from my body so I can play the semiquavers at a greater distance from the bridge, where I can use more bow and the notes will speak. For the ensuing up bow I slant the bow again to approach the bridge in order to maintain the required forte.

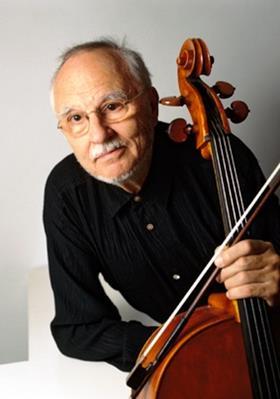

Before his death at the age of 82 in 2012, cellist Gerhard Mantel was principal cellist of the Bergen Philharmonic Orchestra and WDR Symphony Orchestra in Cologne. He was also professor at the Musikhochschule in Frankfurt.

This article was first published in The Strad's July 2006 issue.

No comments yet