Jonathan Govias reviews a book by Geoffrey Baker examining the concept - and feasiblity - of ’social action through music’

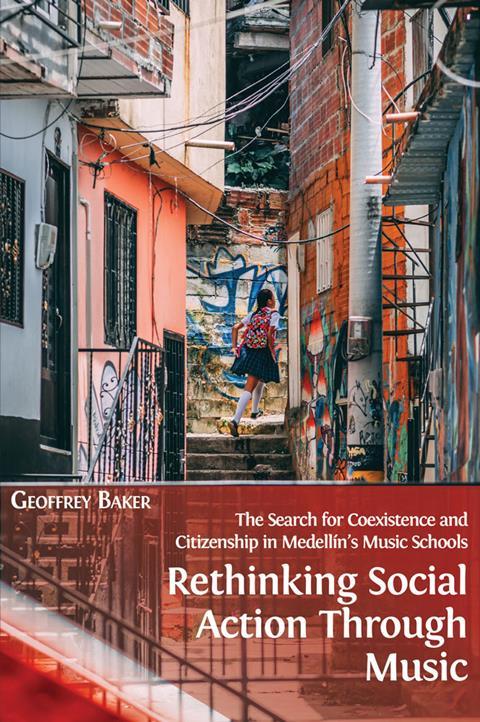

Rethinking Social Action Through Music: The Search for Coexistence and Citizenship in Medellín’s Music Schools

Geoffrey Baker

476PP ISBN 9781800641266

OPEN BOOK PUBLISHERS £26.95

Such is Geoffrey Baker’s infamy in the international El Sistema community that rebuttals, disavowals, and boycotts of his book on the Venezuelan youth orchestra system were in discussion well before its publication in 2014. El Sistema: Orchestrating Venezuela’s Youth was an impeccably researched yet withering critique of an entity many considered beyond reproach. Despite being well-written and insightful, the book was unremittingly negative in style, and Baker’s relentless denunciation of even minor aspects of Sistema prompted legitimate questions concerning the author’s objectivity. Readers seeking guidance found condemnation; those looking for inspiration, discouragement.

In this context, his latest book Rethinking Social Action Through Music can be considered both sequel and course correction for author and audience. Moving beyond national generalisations, Baker engages in a detailed exploration of the evolution of socio-musical outreach work in Colombia’s second largest city, within the Network of Music Schools (known more simply as the Red, the Spanish word for ‘network’). The narrative is far more relevant than its narrow geographic scope might suggest: readers with history in this field will recognise how challenges, paradoxes, questions and ensuing tensions in Medellín echo in similar projects worldwide. Readers without that history will be introduced to the ubiquitous philosophical, pedagogical and operational challenges of the work through Baker’s accurate and illuminating account.

Even a partial litany of the issues confronted by the Red illustrates the dizzying range of considerations concomitant with Social Action Through Music (SATM), a phrase that itself encompasses objectives so vast, multifaceted and multifarious that the primary struggle is to identify which goals, if any, are achievable through music. The social idealism of programme leadership is contrasted by the disinterest, if not outright resistance, of conservatoire-trained music instructors to new pedagogies. All parties grapple with the popular myth that technical excellence in written Western European traditions is proof positive of social impact, when it is frequently achieved through manifestly anti-social means. Indigenous, popular and classical traditions, and their disparate media, teaching methods and objectives, compete for time with each other and with instruction in citizenship and social responsibility in a zero-sum game. The heresy inevitably drawn from these debates is unflinchingly confronted: is music even necessary?

SATM is inescapably complex, and Baker unravels critical intricacies with detail and clarity. His focus on specific challenges in Medellín diffracts into a broad spectrum of inquiry probing the mechanics, possibilities and pitfalls of the sector. Just as spectra defy clean divisions, the inherent interconnection of many concepts produces overlap between chapters as key ideas are explored from multiple angles. A sense of revisitation prevails throughout, but this is a consequence of grappling with complexity, not a failure of organisation. If there were a shortcoming to Baker’s work, it is his embrace of the trope that the string-based orchestra is utterly unsuited to pro-social activity, with contrasting ideas barely elevated above a footnote. The counter-argument is Baker’s own point that the adoption of different genres or media beyond the classical does not automatically confer any social benefit. In a book about possibility, his orchestral myopia is surprising.

Comparisons between Colombia and Venezuela, and Baker’s separate volumes on the two, are inevitable. Baker’s discussion of the Red is considerably more constructive, inviting speculation of what might have been had Sistema in Venezuela evolved through team discourse, not founder fiat; if ‘getting it right’ were viewed as a cycle of listening, learning and unflinching self-examination, not a fait accompli after assembling an orchestra. The inquiry is ruthlessly honest, but not needlessly so: the account of the work in Medellín is appreciative yet objective, bolstered by an informed exploration that gives it international relevance. Worth mentioning is that unlike its predecessor, this volume is available in multiple e-formats without charge. This degree of accessibility for a book of this quality is surprising, but also fitting, given that it succeeds precisely where its precursor fell short, offering guidance, insight and even inspiration.

JONATHAN GOVIAS

No comments yet