Alberto Giordano reviews a survey of Italian luthiers from the 1930s, which gives an insight into the working methods and culture of the time

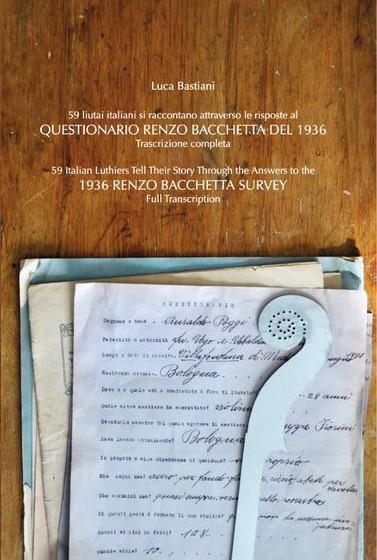

Questionario Renzo Bacchetta del 1936

Ed. Luca Bastiani

238PP ISBN 9791220081627

Luca Bastiani Liutaio €140

In 1937, the bicentenary celebration of Antonio Stradivari’s death was a crucial event for both the city of Cremona and the national and international violin making community. The exhibition organised at the Palazzo Cittanova showcased an important selection of Cremonese and Italian violins from the classical period. As well as the glorification of Italian heritage, it was considered crucial to the support of contemporary lutherie: professor Renzo Bacchetta was put in charge of organising an exhibition of makers’ work and, to check the violin making landscape of the time, he arranged for a survey to be filled out by every luthier currently working. In the letter addressed to each luthier, Bacchetta wrote that he ‘would like to use the occasion to illustrate the life and work of living Italian violin makers, particularly in order to show abroad [that] the tradition of the great masters of the past centuries still continues’.

The survey begins with general information about each maker (biography, address) and goes on with questions on their apprenticeship; i.e. if the maker is professional or amateur, and had ever held another occupation. Then the questions become more specific: how many instruments made per year, the kind of wood used, type of varnish, how many instruments in their collection and so on. Fifty-nine luthiers completed the survey, among them Ansaldo Poggi, Carlo Bisiach, Gaetano Gadda, Cesare Candi, Giuseppe Lecchi, Gaetano and Pietro Sgarabotto, Giuseppe Ornati, Giuseppe Pedrazzini and Gaetano Pollastri. Nine makers answered to the survey in the form of a letter, but unfortunately are not included in this book. The luthiers’ answers clearly reflect their different personalities: some are evidently reluctant while others reveal an outgoing attitude. It’s interesting to note the different answers regarding their individual production: the average is about twelve violins per year, but Azzo Rovescalli claimed he could make up to 45 in the white!

Read: In Focus: A 1953 Giuseppe Ornati violin

Book review: I Segreti di Sgarabotto

The book is well organised and easy to read: the answers to the survey from this considerable group of makers are still interesting, and help give an idea of their work and their personalities. It’s a good research tool for enthusiasts and those who are acquainted with Italian 20th-century violin making.

ALBERTO GIORDANO

No comments yet