Tully Potter reads the autobiography of the superstar British violinist, whose version of Vivaldi’s Four Seasons became the best-selling classical recording of all time

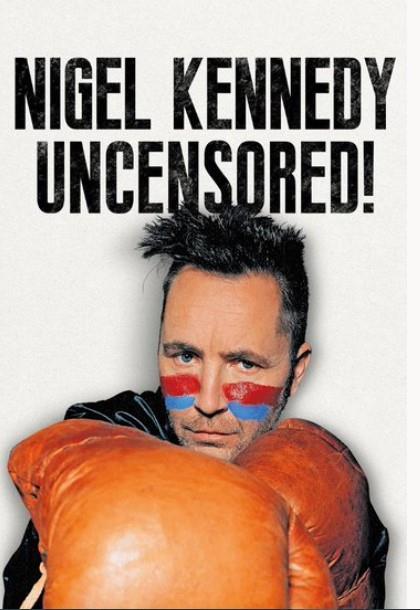

Nigel Kennedy Uncensored!

Nigel Kennedy

320PP ISBN 9781781558560

Fonthill Media £25

How to approach this book, mostly written in a sort of potty-mouthed patois that I find off-putting and infantile? Perhaps, without straying too far into amateur psychology, I can winkle out a few of the reasons why Nigel Kennedy seems desperate to be liked and acquire ‘street cred’.

You have to get to page 75 to discover that Nigel’s Australian father John – RPO principal cellist – abandoned his mother early on. These six pages, which purport to be written from beyond the grave by his grandfather Lauri, one of the best cellists of the interwar years, shows that Nigel, now 65, can produce perfectly decent prose when he wants to. That Nigel uses this chapter to boost his own ego is just one of the annoyances a reader must deal with.

Trying to bring up her son on £5 a month sent to her by John, Nigel’s mother married again – and the boy was landed with the stepfather from hell, who beat his mother up and, when Nigel tried to intervene, went for him with a knife, causing the ten-year-old to spend a night sleeping rough in the park. By then he had been sent to the Menuhin School, which comes across as a pretty chaotic institution in those days. He preferred playing jazz with Stéphane Grappelli – Menuhin himself, whom he claims to admire, was very patient with him – but somehow emerged with credit.

Thousands of students have seemingly thrived at Juilliard, but for our Nige the whole set-up was a hive of ‘Musical Mediocrity’ and all the other students were inferior to him. Dorothy DeLay is the trigger for him to make an obvious play on her name – which he rather spoils by repeating 146 pages later.

The BBC comes in for a good dose of his ire, especially one particular controller (if it was the man I think it was, I have some small sympathy with Nige). His assumed persona, a Punk Violinist, was never going to thrill the powers-that-be.

He is inordinately proud of his first recording of Vivaldi’s Four Seasons, a best-seller through adroit EMI marketing, and gives all his concerto recordings rave reviews. I have met people, otherwise uninterested in classical music, who have bought and enjoyed Kennedy CDs, so perhaps his poses have paid off. But much of this book, which digresses into football, jazz, rock music, boxing and so on, is like ten-year-old Nigel spitting in the faces of a profession and industry that have given him a very good living. Along the way he makes valid points, for example about musical education, but submerges them in his mode of baby talk. More than 80 photos are well reproduced in two sections printed on art paper.

TULLY POTTER

Read: Nigel Kennedy pulls out of Royal Albert Hall concert, citing ‘musical segregation’

Watch: Nigel Kennedy plays Mendelssohn aged 26

Read: Nigel Kennedy: ‘Critics were pretending I was playing out of tune because I’d sold a few records’

Reference

Nigel Kennedy plays Mendelssohn aged 26

No comments yet