The principal viola of the Royal Opera House discusses the connection between opera and Max Bruch’s Romance for Viola and Orchestra

The following extract is from The Strad’s February 2022 issue Masterclass feature on Bruch Romance for Viola and Orchestra op.85. To read it in full, click here to subscribe and login. The February 2022 digital magazine and print edition are on sale now.

Brave beginnings

One of the first times I performed this piece was during a tour in Mexico, in a humongous concert hall that seats around 3,000 people. It was overwhelming, especially because the start is quite nerve-racking! For two bars the mellow strings creep up to where you come in, and then you have to pull yourself together, overcome the adrenalin, and begin. I think the worst mistake is if you start thinking that it’s terrifying. Instead, if you focus on the kind of vibrato and sound you want at the start, soon you’ll be so busy trying to create that effect that it will help to take your mind off your nerves.

Of course, not only do you have to have the right mindset, but you must also have practised, and you have to be ready to play. Having good bowings and fingerings is crucial. Sometimes I write down two versions, because there is always an alternative way of looking at any music. No one can ever be 100 per cent certain that a performance is going to start in exactly the way they intend it to, so be ready to implement a plan B, plan C or plan D, on the spot, if necessary.

A connection to the opera

Bruch wrote this piece for Maurice Vieux, who was at that time the principal violist of the Paris Opera. That is a connection that I enjoy in particular, because I am one of the principal violists of the Royal Opera House in Covent Garden, London. At the moment we’re rehearsing the ballet Giselle, by Adolphe Adam, and in the second act there’s a pas de deux with a wonderful, famous viola solo that to me sounds similar to the opening solo of Berlioz’s Harold in Italy, with all of its lushness and its harp accompaniment. In both these pieces, and also in Bruch’s Romance, the viola timbre is so like a human voice. Try to open up the overtones of the instrument, to explore that vocal sound as though you’re singing an opera aria, to create that same wonderful atmosphere.

Bruch wrote the Romance in such a beautiful way that I don’t feel there is much need for rubato. If you just stick to what is written on the page, it will make sense. Sometimes people play a major ritenuto into the orchestral material immediately before figure B, but I don’t do too much here, because I feel that it breaks the sense of continuity as you hand the material over to the orchestra, and it makes it more difficult for the conductor to take over.

To me, this music is like a small, romantic novel, written in a noble, subtle way, so I wouldn’t over-indulge in vibrato either, or it can sound too sickly. Take a step back and don’t do too much – the best desserts are the ones that aren’t too sweet. For example, after the orchestra takes over the theme from figure B, the viola has a second solo, this time in forte. If you overdo the dynamics or your vibrato here, you won’t have anything left to give for the real climax at figure F.

Read: Masterclass: Bruch Romance for Viola and Orchestra op.85

Read: Masterclass: Antoine Tamestit on Brahms Viola Sonata op.120 no.1 third and fourth movements

Read: ‘Take it, make it work and don’t hurt yourself’ - tips for small framed violists

-

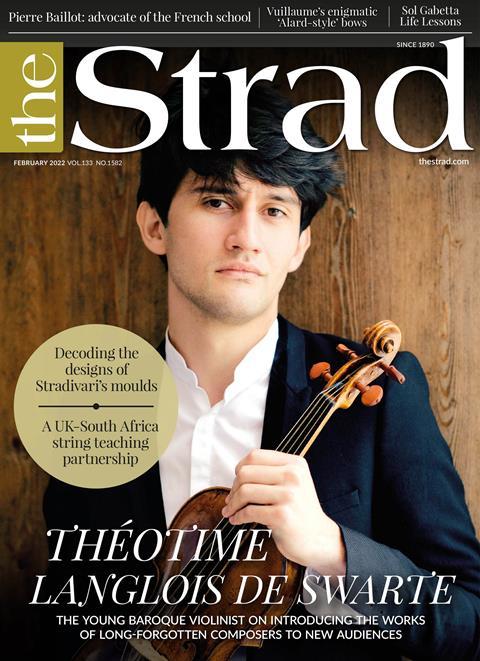

This article was published in the February 2022 Théotime Langlois de Swarte issue

The Baroque violinist’s career has taken off in the past year. Charlotte Gardner talks to him about his quest to popularise the works of long-lost composers. Explore all the articles in this issue . Explore all the articles in this issue

More from this issue…

- Théotime Langlois de Swarte

- Vuillaume’s ‘Alard’ Bows

- Pierre Baillot

- United Strings of Europe

- Cremonese Violin Moulds

- Arco Project

Read more playing content here

-

No comments yet